Visualize This

Friday, September 7th, 2007September 7, 2007

Washington, DC

“I’ve always liked listening to the radio…That’s one of the reasons why in a lot of my books there’s somebody listening through a wall to somebody talking. Somebody’s always talking in another room. Maybe that’s the radio.” — Ernest J. Gaines

I don’t trust a library without a radio in it. In the Big Read’s book-jammed office right now, I’m listening to Scott Joplin’s “Solace,” marveling at how all his melancholy, plangent numbers mean so much more to me than years ago, when I only had ears for “The Maple Leaf” and Joplin’s other, more upbeat rags.

Radio’s much on my mind these days, since this coming week marks the premiere of The Big Read on XM, our new national weekday show. In case you haven’t heard, XM Satellite Radio is airing each of the Big Read audiobooks in turn, courtesy of Audible, Inc. Each book will be bracketed beforehand by the NEA-produced CD devoted to the novel in question, and after by a roundtable discussion of the book amongst me and a couple-three distinguished fellow readers — all ringmastered by XM Sonic Theater’s book-besotted host, Jo Reed. The first episode airs Monday at 2:30 am, 10:30 am and 4:30 pm Eastern time. (Bear in mind that Pacific time, as we used to say in California, is three hours behind and roughly a decade ahead.)

The first book will be Fahrenheit 451, read by Ray Bradbury himself. Over at XM last week, I joined in a wide-ranging, provocative conversation about Fahrenheit with Readers Circle member Nancy Pearl, Ender’s Game author Orson Scott Card, XM’s own Kim Alexander, and the sainted Jo. This, plus an interview about the show with XM’s Bob Edwards (taking a holiday from our fortnightly movie chats), and a few extra minutes of me jawing about the Big Read in general. All in all, not a bad way to get the word out to those few scattered Americans not yet doing a Big Read or following this blog with fanatical zeal.

|

|

|

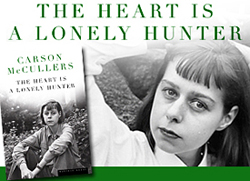

Carson McCullers |

The Big Read on XM represents just the latest chapter in the long, happy marriage of radio and literature. Dan Brady wrote in this space the other day about the recurrence of bridge-playing in several of our books, but radio may be even more pervasive. Most famously, Bradbury presents radio in Fahrenheit as an insidious force, anticipating the Walkmen and iPods with his descriptions of “seashell” or “thimble” radios “tamped into” oppressed citizens’ ears. More benevolent are characterizations of radio in both The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, in which classical music broadcasts become Mick’s solace and salvation, and A Lesson Before Dying, where Jefferson’s jailhouse radio gives him one tenuous nighttime connection to the outside world.

These two literary uses of radio strike me as ultimately truer to life than Bradbury’s cautionary one — though radio’s visual inheritors have a lot more to answer for. Unlike later electronic media, radio (whether delivered via satellite, computer, or crystal set) has one crucial thing in common with literature. It cultivates the very skill that too many educators today find alarmingly absent from their classrooms: the ability of students to make up their own pictures…