Celeste Biever

(Part One of Two)

In the past, a simple hand-scrawled signature would be enough to establish your identity. Today, we need a bewildering assortment of computer-readable passports, driver's licences, credit card numbers, logins and passwords to identify ourselves when we travel, shop, bank and work. In short, our digital identity is becoming more important than our physical identity. And that's just the start of the identity revolution. Soon biometrics will transform what it takes to prove who you are.

In the past, a simple hand-scrawled signature would be enough to establish your identity. Today, we need a bewildering assortment of computer-readable passports, driver's licences, credit card numbers, logins and passwords to identify ourselves when we travel, shop, bank and work. In short, our digital identity is becoming more important than our physical identity. And that's just the start of the identity revolution. Soon biometrics will transform what it takes to prove who you are.

In a two-part special report starting this week, New Scientist investigates this trend and how it will change society. Will your digital identity become the pass key to a future without fraud, providing instant access to services, and improved security? Or will it lead to an Orwellian nightmare of permanent surveillance, curtailed civil liberties and an underclass of identity have-nots?

"OPEN your eyes," says a stern, automated voice. I look into a mirror the size of a small chocolate bar and wait for the click. "Thank you," says the voice. "We have finished taking pictures of your eyes."

It was my first taste of the biometric future. The machine was an iris-scanning device, and the pictures it took will be used to translate the patterns on my irises into a unique digital code. The idea is that later I will be able to use my irises to prove I am who I say I am, just by opening my eyes to show they match my code.

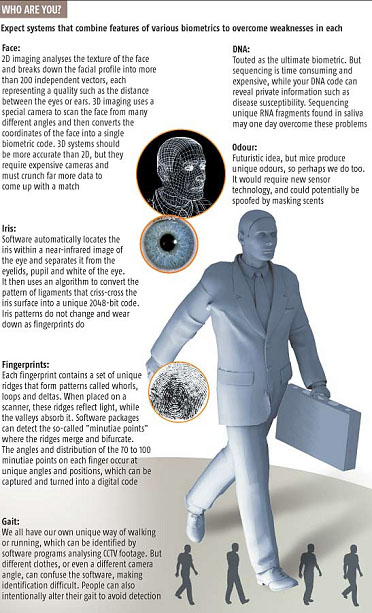

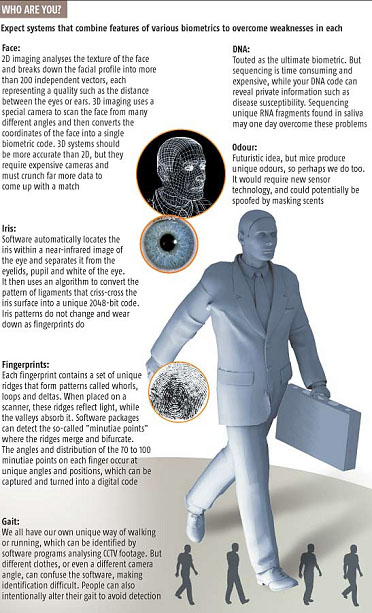

Similar biometric machines, which identify individuals by measuring physical attributes such as the whorls within their fingerprints or the shape of their faces, are already being rolled out in airports and at passport controls around the world. And their use is expected to grow massively - and not just for security purposes. Biometrics will soon hold the key to your future, allowing you and only you to access your house, car, finances, medical records and workplace.

Slowly and quietly, a revolution in biometric technology is taking place, one that will transform your life and change the very idea of what identity means. The command to "open your eyes" seems strangely appropriate.

For as long as people have roamed beyond their family or home village, they have needed to be able to establish their identity - to show other people that they are who they say they are. Nowadays our identity is perhaps our most valued asset, encapsulating our name, our history, our reputation and our status. With it we are someone others can deal with and trust. Without it we are nothing.

Yet the way we identify each other is changing fast. In a world of the internet and global travel, being recognised by sight is not an option. Even a birth certificate or neatly written signature is no longer deemed sufficient as a guarantee of someone's identity.

Take, for example, what happens when you decide to travel overseas. First you have to buy a ticket, which nowadays involves remembering any number of passwords to log onto various internet accounts. Then provide a credit card number, checked against personal details such as your PIN number or mother's maiden name. And finally, a passport at the airport.

But this cumbersome hotchpotch of checks will soon be a thing of the past. A host of biometric technologies are being worked on that will identify you almost instantly, and much more accurately than before, improving the security of ID checks and taking away much of the hassle for the people being identified. That, at least, is the dream. The reality, as with all technologies, is that it will not always work. And when the system goes wrong, the implications can be profound.

The good old-fashioned fingerprint is the biometric with the longest pedigree, thanks mainly to its use by the criminal justice system. The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), based in Gaithersburg, Maryland, has a database of 28 million fingerprints, which it uses to hone and test print-recognising computer algorithms. "Fingerprint technology is mature," says fingerprint and biometrics expert Anil Jain of Michigan State University in East Lansing. "We want to take systems that have been used in criminal justice into large-scale civilian applications where ordinary people will use them every day."

This is starting to happen. Fingerprint scanners made by companies such as Digital Persona in Redwood City, California, are already freeing personal computer users from the annoyance of having to remember a plethora of passwords. A scan of the user's print is converted into a digital code that is fed into the computer and used instead of the password for tasks such as logging on and accessing email. Digital's co-founder Vance Bjorn reckons that fingerprint systems should enhance security, as doing away with passwords will encourage people to log off when they are away from their computers, rather than leaving them running.

Digital Persona scanners are also being used in Mexico to allow people without social security numbers or driving licences to bank securely. "These people were not in the system. Now they are benefiting from a stronger form of identity," says Bjorn.

Unfortunately, fingerprint scanners are far from foolproof. They may not record a clear print from sweaty, dirty fingers or those cut or bruised, or smoothed by hard labour. Worse, fingerprints can be copied, or "spoofed". Three years ago, Tsutomu Matsumoto and colleagues from Yokohama National University in Japan tricked a range of commercial scanners by making gelatin mock-ups of fingerprints lifted from glass. This has sparked a race to incorporate a "liveness" test into biometric systems.

Once a scan has been obtained, the next step is to compare it with existing scans to discover whether or not it is a match, and this is where the problems really start. Take the U.S. Visitor and Immigration Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) operated by the US immigration authorities. The system scans both index fingers of every non-resident visitor to US shores, and every visa applicant. When visa applicants arrive, their prints are checked against the ones taken when they applied for the visa to verify it is the same person. In this situation, comparing a few prints is relatively easy, with an accuracy of between 99.6 and 99.8 per cent, according to NIST.

But the US-VISIT project runs up against problems when used for other purposes: namely detecting visa fraud by checking applicants against existing visa holders and flagging up the application if it finds a duplicate of the print, and checking against a watch list of prints of suspected terrorists and criminals. Matching a set of prints against the millions of others in the database or on the watch list is much harder than just checking them against the single print obtained when the visa was issued. NIST says that for these kinds of match the system is only 96 per cent accurate and this falls to 53 per cent if the prints are low quality. To improve accuracy rates, NIST has recommended since 2002 that all 10 fingers be used, raising the accuracy to over 99.95 per cent. In July the US government said it would work towards implementing this.

But the more prints that need to be taken and analysed, the more cumbersome the ID system becomes, which undermines the idea that it could provide precise, speedy passport controls. People also dislike giving fingerprints because of their long-standing association with crime, or because they feel touching scanners used by thousands of people is unhygienic.

High hopes

Among alternatives, the technology upon which most hopes are pinned is iris recognition. "The iris is inside the body, but protected by a transparent membrane. It's the ideal body part for biometrics," says Markus Kuhn, a computer security expert at the University of Cambridge.

Iris recognition is less well tested than fingerprinting, but should be more reliable. Iris recognition systems take a near-infrared image of the eye, then use software algorithms devised by John Daugman, also at the University of Cambridge, to convert the unique pattern of the iris into a 2048-bit code.

If the original iris scan is good, the chances of the algorithms incorrectly matching two irises are less than 1 in 2 billion, says Daugman. Capture and compare two irises from each person, and the odds become so small that in theory the system could be relied on to distinguish between every individual on the planet.

The technology has been embraced by the Nation's Missing Children Organization, based in Phoenix, Arizona, which runs the US Children's Identification and Location Database. The NMCO has started registering iris scans of children across the country, in the hope that if any subsequently go missing and are then found the police can readily identify them. The organisers plan to also start scanning people with dementia, so that they too can be easily identified if they become lost and confused.

Like other biometric systems, iris recognition has drawbacks. In May, the International Biometric Group (IBG), a consultancy based in New York city, conducted the first independent tests of such systems. It found that while iris recognition software is very good at matching two iris scans from a person enrolled in a system, it can be difficult to capture a template of someone's iris in the first place. "With certain people the rejection rate is pretty outrageous," says Michael Thieme of IBG.

Part of the problem arises from people not knowing how to behave when their iris is being scanned. They may blink too often, stand too far away from the scanner, or allow their eyelids to droop. That can result in an unacceptable number of false negatives, in which the system later fails to recognise a person's scan.

Till now, it has been hard to find ways around this. All existing iris recognition systems are based on patents held by Daugman, who has licensed them to Iridian, a company in Moorestown, New Jersey. But one of the patents has just run out, with more to follow next year, and this has led to a flurry of research. For example, Don Monro of the University of Bath, UK, hopes to cut the number of false negatives while not adding to the number of false positives - occasions when a scan is matched to the wrong person. Daugman says he is now allowing people implementing his algorithms to adjust the threshold for accepting and matching iris scans, to make them more or less stringent depending on the application. The idea is to allow a lower threshold, with few false negatives but an increased risk of a false positive, to be set for everyday use, while maintaining the high threshold for top-security use where even a small number of false positives is unacceptable.

Other biometric technologies are also being considered, such as DNA testing, and systems that identify the unique way you walk or even smell. Governments are especially keen on identifying people using the physical characteristics of their face. Such technology would complement current ID card and passport schemes that rely on photos, and would allow people to be ID'd remotely or from CCTV footage. This biometric "is always going to be the most appealing," says expert Mark Nixon, at the University of Southampton, UK.

But the technology got off to an embarrassing false start with two attempts to implement it in 2002. One was a trial at Boston's Logan airport, where it was meant to spot suspected criminals and terrorists. The other was an actual implementation by the police department in Tampa, Florida, who installed it at a football stadium and in a neighbourhood with a lot of nightclubs in an attempt to spot known criminals. Studies published by the American Civil Liberties Union showed that it produced an unacceptable number of false positives, while failing to spot known criminals. The Tampa police abandoned the system after less than a year, and the airport never fully deployed it.

Beards, sunglasses, varying hairstyles and even natural ageing have all proved problematic for face-recognition systems. But the technology is improving. The states of Colorado and Kansas use the technique to screen out fraudulent attempts to apply for duplicate driver's licences, while the US government does the same to avoid multiple applications for travel visas and Green Card work permits. Identix, a firm based in Minnetonka, Minnesota, which provides the face recognition software for the driver's licenses and the government, also has a contract with the Mexican Federal Election Institute (IFE) which uses the technology to scan the faces of members of the public to prevent them voting twice, while Japanese firm Omron is embedding technology in mobile phones that will check an image of the user's face as a more secure login than a conventional PIN.

Face check

No independent test of these systems has been conducted since the 2002 debacle, however. And all systems in use so far are based on identifying cooperative people who know their photo is being taken under controlled conditions and at a set distance from a camera. What law enforcement and security services really want is to be able to identify less cooperative people from a distance. Next month, NIST will start evaluating 19 face recognition technologies as part of its "Face Recognition Grand Challenge".

It seems unlikely that any single ID technology will reign supreme. Instead we can expect to see systems that combine the best features of various biometrics while compensating for the weaknesses inherent in each.

Combining a scan of your face or iris with your fingerprints, for example, will produce a "super ID" that can confirm who you are far more reliably than each method alone, while making it much harder for cheats to fool the software. And making use of a range of biometrics would allow people to be ID'd who do not have suitable fingerprints or irises, or who may not want to show their face - for religious reasons, for instance. "Eventually we are going multi-modal," says Martin Herman, head of biometrics at NIST.

That's the idea, at least. But making it happen is likely to prove tricky. For instance, how will algorithms combine the different kinds of data? Should more emphasis be placed on the accuracy of the match between your fingerprints, or on iris scans? In a bid to tackle the problem, NIST will ask 10,000 people to sit in its so-called multi-modal biometric accuracy research kiosk, and have their fingerprints, faces and eyes scanned. This will be done twice, six months apart, and researchers will use the data to work out the best way to fuse these different technologies. And one day, they hope, that will allow everyone to be labelled with a super ID.

When that day arrives the identity of every one of us will be reduced to a single number - and the implications will be profound. We will be investigating them in depth in the second instalment of New Scientist's special report into Identity next week.

|

Identity theft

Digital IDs are already with us, even if they lack the detail that will come with biometric IDs. Stored in our credit card and PIN numbers, passwords, driver's licence, social security details and bank statements is digitised information that can be pieced together by criminals. They can use the fake ID to steal money from our bank and credit card accounts, obtain loans or benefits in our name, or apply for jobs using our personal records.

Some 9.3 million US citizens suffered identity theft last year, according to the Federal Trade Commission, while the UK Home Office says 100,000 Britons suffered the same fate. Many of these cases were the result of avoidable lapses in IT security by the firms that banks and government agencies use to hold detailed information on us all.

In April a password security breach at Seisint, which collates information on individuals for the US Department of Homeland Security and the police, allowed intruders access to personal information on 310,000 people, including social security and driver's licence numbers. The intruders gained access by using the logins and passwords of legitimate subscribers.

In May credit card payment processor CardSystems Solutions of Atlanta, Georgia, revealed it had left unencrypted records of 40 million MasterCard and Visa transactions on its IT system that could be accessed via the internet. A hacker subsequently installed a small program to extract vulnerable records, including at least 200,000 credit card numbers.

These breaches were largely caused by easily fixed deficiencies in IT security. "Identity theft isn't primarily a technical issue, but a policy one," says computer scientist Ross Anderson of the University of Cambridge. But Neil Fisher, director of security and intelligence at UK defence technology firm Qinetiq, says a "gold standard ID card", based on reliable biometrics, will make it more difficult for criminals who steal personal information to gain access to people's bank or credit card accounts. "Probably by 2014 we will depend on cards and ID theft will be at a much lower level," he says.

Paul Marks

|

|

ID cards on the way

The US and UK are pushing ahead with plans to introduce identity cards and biometric passports. But both schemes are under attack from those who say they are badly thought out and costly, and that far from improving security they could open up new threats.

The ID cards proposed in the US and UK will require citizens' personal details to be stored on central databases. Both governments are vague about what information the ID cards will carry and who will have access to the databases.

In May this year the US senate approved the Real ID Act, which will introduce electronic driver's licences. Starting in May 2008, each licence will carry a chip holding its owner's digital photo, name, address, social security number and digitised birth certificate. The Department of Homeland Security can add further biometrics to that list, and states will link their databases and share information.

The licence, or an equivalent ID card, will have to be presented whenever US law requires an ID check: for instance, when boarding a plane or opening a bank account. This will make electronic IDs virtually compulsory. The ID cards follow electronic passports the US will begin issuing in December. These will contain a chip with biographical and passport information along with a digitised photo, and in future may also carry digitised fingerprints and iris scans. From October 2006, new passports issued by countries covered by the US Visa Waiver Program must also carry a digitised photo and data on a chip.

The UK government is pressing ahead with plans to introduce ID cards. From 2008, people applying for a passport will also be able to obtain an ID card, as part of a voluntary scheme that is likely to become compulsory later. While recording a digital photo and fingerprints for their passport, Britons would also record an iris scan for their ID card, information that would be held on the National Identity Register (NIR), stored on a government database. The government recommends that the NIR include 49 types of information, including biometrics, address and driver number. It estimates that a passport and card together will cost about �. The bill does not specify what personal information will be stored on each ID card's chip. It is also unclear when verifying information will require online access to the database, and when a check of the card's chip will suffice.

In June, a report published by the London School of Economics estimated the likely cost of a card plus passport at �0, and says the proposals are "too complex, technically unsafe" and "lack public trust and confidence". The report argues that the vast quantity of personal information held in the central database makes it a potential security risk.

The LSE report advocates a model in which the central database contains minimal information that does not require updating, while information on the cards is kept up to date locally by organisations such as banks. The government remains committed to a centralised database to prevent fraudsters registering multiple identities.

Hazel Muir

|

In the past, a simple hand-scrawled signature would be enough to establish your identity. Today, we need a bewildering assortment of computer-readable passports, driver's licences, credit card numbers, logins and passwords to identify ourselves when we travel, shop, bank and work. In short, our digital identity is becoming more important than our physical identity. And that's just the start of the identity revolution. Soon biometrics will transform what it takes to prove who you are.

In the past, a simple hand-scrawled signature would be enough to establish your identity. Today, we need a bewildering assortment of computer-readable passports, driver's licences, credit card numbers, logins and passwords to identify ourselves when we travel, shop, bank and work. In short, our digital identity is becoming more important than our physical identity. And that's just the start of the identity revolution. Soon biometrics will transform what it takes to prove who you are.