Four Freedoms for the Fourth

Today, and every day, the people of this land are grateful for our freedom… Every year on this date, we take special pride in the founding generation, the men and women who waged a desperate fight to overcome tyranny and live in freedom.

—President George W. Bush, speaking in Ohio on July 4, 2003.

July 4, 2004 marks the 228th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The holiday generally focuses on the contributions of the founding generation, but it also reminds us that the freedom we have inherited from the founders is re-earned, refined, and re-shaped in every generation. From small-town mayors to members of Congress to the President of the United States, public officials across the country have traditionally honored the Fourth by offering their own toasts to freedom.

Of course, freedom is a common theme of American political oratory not only on July 4, but all year long. We are so accustomed to hearing freedom invoked rhetorically as a matter of course, that for many, the word has come to signify little more than something to feel vaguely good about. And yet, some of the most thought-provoking musings on freedom can be found in public speeches like those heard all over the country on Independence Day and every day.

Political oratory is an excellent, though sometimes overlooked, place to begin a critical examination of the meaning of “freedom” within the national discourse. Fourth of July speeches, in particular, offer a great opportunity to reflect on the ways in which freedom is being defined—and continuously redefined—in the public square. The Fourth is a powerful reminder that our sense of freedom is shaped not only through written texts, but also through public oration.

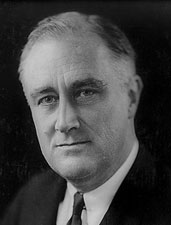

One of the most famous political speeches on freedom in the twentieth century was delivered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his 1941 State of the Union message to Congress. The address is commonly known as the “Four Freedoms” speech, and an excerpt is available through the EDSITEment-reviewed website POTUS—Presidents of the United States. In the relevant part of the speech, President Roosevelt announced:

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.

In bold and plain language, Roosevelt’s declaration raises many of the key questions underlying any discussion of freedom. An entire EDSITEment lesson plan, The Legacy of FDR’s “Four Freedoms,” is devoted to an in-depth study of those questions. An abbreviated version of the activities described in The Legacy of FDR’s “Four Freedoms” is provided below:

Activities and Questions for Discussion Based on FDR’s “Four Freedoms”:

Which freedoms are most essential?

Parents and teachers can encourage students to think about the significance of the four freedoms listed by FDR: expression, worship, economic prosperity, and physical security.

- Why do you suppose that these were the four freedoms he chose to highlight as “essential?”

Which potential freedoms did the President leave out?

How did the historical circumstances of the speech (delivered in early 1941, eleven months before Pearl Harbor) contribute to FDR’s emphasis on these particular freedoms?

Before showing students the text of the “Four Freedoms” speech, parents and teachers can ask students what they would name as the four most essential freedoms.

- How do the students’ selections differ from each other?

- How do the class picks differ from the freedoms highlighted by FDR?

- Does the class reach consensus on any particular freedom?

Freedom TO or freedom FROM?

Notice that two of FDR’s four freedoms are framed as freedom to do something: freedom to speak one’s mind and freedom to worship as one sees fit. The other two freedoms are framed in terms of freedom from something: freedom from want and freedom from fear. Many scholars have taken care to distinguish sharply between these two types of freedom. The British political philosopher Isaiah Berlin called “freedom from…” negative liberty; he called “freedom to…” positive liberty. Here is how Berlin defines those terms:

Negative liberty is the absence of obstacles, barriers or constraints… Positive liberty is the possibility of acting—or the fact of acting—in such a way as to take control of one's life and realize one's fundamental purposes.

Of course, positive and negative liberty do not always describe two entirely different forms of freedom—they are often just two different ways of thinking about the same freedom. A single freedom might be conceived as the presence of a clear path to happiness or alternatively as the absence of obstacles to happiness. Almost any freedom can be expressed either as freedom TO or freedom FROM. “Freedom to worship God” in one’s own way (FDR’s second freedom) can just as easily be expressed as freedom from religious coercion. Similarly, “freedom from want” (FDR’s third freedom) can just as easily be expressed as freedom to have a full stomach.

While positive and negative conceptions of freedom often represent two ways of saying the same thing, there are instances in which “freedom to” and “freedom from” do conflict. We can imagine a situation in which a person is subject to no external constraints but is not, on his own, able to support his basic needs or pursue his fondest ambitions. In other words, he is held back not by externally imposed restrictions, but by his own personal limitations. The person has “freedom FROM,” but not “freedom TO.” There is sometimes a tradeoff to be negotiated between these two dimensions of freedom. Students can discuss situations that might involve such a tradeoff and think about how they would resolve such situations.

Theorists have long argued about which idea of freedom should be honored by governments. Proponents of “negative liberty” contend that governments should avoid interfering with the private decisions of its citizens. “Freedom from” can therefore be understood as the ideal of non-coercion. Proponents of “positive liberty” suggest that governments should intervene to make it possible for their citizens to achieve certain ends. “Freedom to” can thus be understood as the ideal of empowerment.

Parents and teachers can explore the distinction between “freedom from” and “freedom to” by discussing with students the following question: Are the liberties guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution most readily understood as “negative” or “positive” liberties—or some combination?

The question can also be addressed on a more immediate level. Teenagers tend to enjoy the freedom that comes with being able to drive. But when they ask their parents for the keys to the car, are they enjoying the freedom from parental interference or are they enjoying the freedom to go out and see their friends whenever they wish? Ask your students which idea of freedom most closely resembles their way of thinking.

Is the idea of freedom universal?

Notice that President Roosevelt’s vision of freedom is a universal one. He emphasizes his hope that each of the freedoms he lists will take hold “everywhere in the world.” Students might want to comment on this aspect of FDR’s message.

- Is it possible to distinguish between ideas of freedom that are specific to certain times and places and ideas of freedom that are universal?

What does the Declaration of Independence tell us about the universality of human freedom?

How should we address disagreement about the meaning of freedom?

In the long run, can more than one idea of freedom coexist within a single nation? Within the world?

If desired, these activities can be used to introduce the issues involved in some of the landmark cases addressing the interpretation of Constitutionally protected freedoms. The EDSITEment lesson plan The First Amendment: What's Fair in a Free Country provides a basic survey of a number of cases exploring the scope of the First Amendment’s free speech guarantee.

Interested students can also explore more examples of American political oratory by visiting two EDSITEment reviewed websites: Great American Speeches and Presidential Speeches. The theme of freedom is particularly prominent in the speeches of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan.

Of course, political oratory is only one vantage point from which to view the ongoing process of defining freedom. Biographies, histories, and even novels all play a role in that process. For a selection of classic books offering key insights into the meaning of freedom in the United States and throughout the world, please consult NEH’s We the People Bookshelf on Freedom. EDSITEment’s July NEH Spotlight suggests ways to use EDSITEment resources to enrich the study of the books on the We the People reading list.

The summer—and the Fourth of July in particular—presents an opportunity for students to reflect on the ways in which they casually invoke freedom in their daily lives. For instance, when we say that we can’t wait for the freedom of summer vacation, what do we mean by that? What exactly is “freer” about our lives during the summer?

Freedom, it turns out, is a rather versatile word. A President addressing Congress and a student anticipating the arrival of summer will both shout “Freedom!” when asked what it is they hope to achieve. Our hope is that EDSITEment will help students of all ages explore the full range of aspirations that are echoed in the call of—and for—freedom.

Standards:

National Council for the Social Studies:

ii – Time, continuity, and change

v – Individuals, groups, and institutions

vi – Power, authority, and governance

x – Civic ideals and practices

National Standards for Civics and Government:

I.B – What are the essential characteristics of limited and unlimited government?

V.B – What are the rights of citizens?

|