-

Community Stories

-

ASARCO

-

Public Health

-

Other

Hayden, AZ

King Copper

Arizona mining has been marked by a long history of industrial strife, especially for Mexican-Americans who have faced community and workplace discrimination. Much has been written about the persistent mistreatment of and prejudice toward Hispanic workers and their families in Arizona, including two-tiered wage systems, segregated housing, discriminatory patterns of exposure to hazards and restricted access to just and effective remedies. In this essay we explore some of the stories and struggles we’ve learned from our research and from Hispanic miners and community members living and working in Arizona’s copper belt.

In the early years of the 20th century, the celebrated jurist Felix Frankfurter served on a presidential commission regarding industrial conflicts. He expressed a studied outrage at how Mexican workers were being treated in mining operations across Arizona.

The miners feel that they are not treated as men…without a share in determining the conditions of their labor, and their labor is their life…. in a word there is no fellowship for them in the great industrial enterprise which absorbs them. (Parrish, pg. 29)

During World War One, non-compliant workers involved in labor organizing and strikes were blacklisted, especially if they were not US citizens. Mexican miners and smelterworkers were often targets for induction into the military, even while their efforts to become naturalized citizens were being undermined. Some faced jail or deportation. During the war and the “Red Scare” that followed, parts of Arizona’s copper belt were described as a police state. The copper companies maintained stringent control of communities where their mines and smelters were sited; according to Parrish, “the copper companies easily maintained de facto control over the substance of local policy.”(Parrish, pg. 49)

Between World Wars One and Two, and into the 1950s, a pattern of separation and discrimination hardened in Arizona. The “Copper Collar” tightened as copper barons exerted their brand of industrial peace and progress. This involved structural discrimination in housing and jobs, as well as persistent surveillance and red-baiting. The famous (and famously black-listed) film “Salt of the Earth” portrayed the struggles of Mexican and Mexican-American miners and their families, including the women’s efforts to get the Mine, Mill and Smelterworkers Union to add indoor plumbing and hot running water to its strike demands. Both were available to Anglo families, but denied to Mexicans.

The regional disparity in how workers were treated and compensated became clear with the 1944 report of the Federal Equal Employment Commission:

There is a wide spread between the labor scale in effect in the Southwest, where most of the laborers are of Spanish extraction, than [what is] in effect in Idaho, Montana and Utah fields. The spread becomes significant when it is remembered that the copper companies, whether located in the North or in the Southwest, receive the same return for their product.”(quoted in Bustamente, 1995)

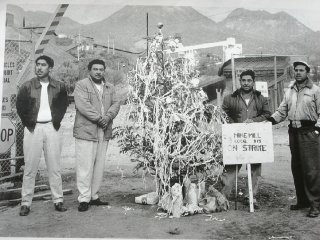

Miners and their families continued to struggle with mining companies in Arizona through the 1980’s. In 1983 2400 workers in Clifton/Morenci, members of 13 international unions, went on strike against their employer, the mining giant, Phelps-Dodge. The unions were opposing wage and benefit cuts imposed by the company in violation of an industry-wide contract that had already been ratified by other mining companies. During this protracted and closely observed strike, the laboring communities of ASARCO, Kennecott, Inspiration and Magma Mining Companies saw Phelps Dodge operate with virtual impunity. The company hired replacement workers and worked closely with the state of Arizona to conduct extensive surveillance of the strikers. Governor Babbitt called in state troopers and the National Guard to prevent the unions from enforcing their picket line, and many workers were jailed. In Holding the Line, Barbara Kingsolver writes of the “ironclad, steel-toed partnership” between the state, the police and Phelps-Dodge that crushed the strike. For many families, the disastrous conclusion to the strike, created permanent unemployment and destitution.

In 1995, on the 12th anniversary of the Clifton/Morenci strike, Jonathan Rosenblum wrote about the little-known surveillance strategies adopted by the state through its Arizona State Criminal Intelligence Systems Agency (ACISA). to support Phelps-Dodge in breaking the strike. Rosenblum wrote that ACISA “hired union informants, bugged union meetings, and created a computer database on anyone suspected by the agents of being a ‘troublemaker.’” Rosenblum quoted ACISA Chief Navarrete’s defense of his agency’s activities, “What happened during the strike doesn’t fall within the definition of organized crime, but from my perspective, it’s organized labor’” (http://www.tucsonweekly.com/tw/06-29-95/curr4.htm)

In his book, Copper Crucible, Rosenblum explains how corporate-state response to the strike changed the playing field for unions:

This old weapon (replacement workers) was upgraded and modernized in ways that tilted the playing field in favor of management and brought back with a vengeance the “fungibility” (or replaceability) of labor. (Rosenblum, pg. 222)

To the mix of persistent ethnic prejudice and strengthened management strong-arming of working people and their unions, add the devolving environmental conditions in mining/smelting communities. In 1982, a community group at one of the Phelps Dodge smelters in Douglas, released a blistering account of airborne pollution reaching into a large region of southeast Arizona and southwest New Mexico, as well as growing evidence of on-the-ground impacts of cancer and serious pulmonary diseases. While Tucson and Phoenix had plans for attainment of Air Quality Standards under federal law, the small smelter towns across the state had no plans, due to limited or shrouded data, the power of the mining-smelting sector and the non-attention of federal regulators. Increasingly, “what are we breathing?” became the question at smelter towns across the state.

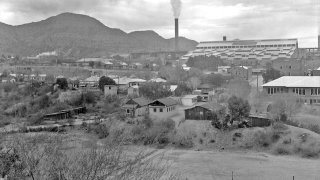

Miners in Pinal County: The Growth and Death of Company Towns

Hayden is a small mining/smelter town located partly in Gila County and partly in Pinal County in the southeast part of the state. Along with the neighboring town of Winkelman it is the community and worker base for Asarco’s smelter, the last operating smelter in the US. Hayden has a complex history: originally founded as a company town, it was shaped by patterns of immigration over many generations, ethnic prejudice and discrimination, volatility of strikes and union-management relations, and the ever-growing dreary and dramatic evidence of health and environmental damage.

Hayden’s development is inextricably connected to the broader history of mining in the region. The town was founded in 1909 as a wholly owned entity of the Ray Consolidated Copper Company, part of the Guggenheim corporate group which also held the controlling interest in ASARCO. It was based near the confluence of the Gila and San Pedro rivers to provide housing, for primarily Mexican workers who migrated to the region to build the smelter. In 1912 the company completed construction of the Hayden smelter and began processing ore from the Ray underground copper mine, 17 miles down the road. Ray Consolidated was purchased by Nevada Consolidated, and then by Kennecott Copper in 1933. Through this purchase Kennecott acquired ownership of the company town of Hayden. In 1958 Kennecott began operating a second smelter in Hayden, but it closed in the 1980’s.

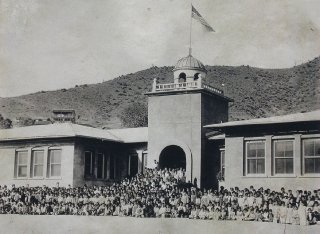

In its earliest days the Ray copper mine was owned by Mineral Creek Mining Company; in 1910, the year after Hayden was founded, it was purchased by Hayden’s owner, Ray Consolidated. In 1933 ownership of the mine passed to Kennecott Copper, By then, three segregated communities were located near the mine. Beginning in 1906 the town of Sonora housed Syrian families and Mexican workers and their families who had been recruited from Sonora, Mexico. The town of Ray was built in 1909 to provide housing for Anglo and Irish workers. In 1911 a third town was founded by Spanish miners and named “Barcelona” after their city of origin.

Labor historian Philip Mellinger has cited the significance of the Ray mine to labor organizing labor in the state:

Arizona’s first World War-era labor activism began with a series of incidents at Ray…Ray, Sonora and Barcelona became a hornet’s nest of social activism which would not subside until after the First World War”(quoted in Seefeldt 2005, p. 7)

Mining operations were influenced by the fluctuations in price and demand in the copper industry; closures of the mine, in turn, affected the residential population. Sonora’s population grew to 5,000 by 1912; but during the early 1930’s when the mine closed, Kennecott agreed to send miners back to Mexico at company expense. By the mid-1930’s the population of Sonora had diminished to 600. Then in 1937 the mine re-opened, and the population once again expanded.

In the 1950’s Kennecott’s underground mine was converted into a vast open-pit mine, and as it grew the three communities were wiped out. A news article published in 1959 reported, “gradually the pit expanded. The Old Man of the Mountain, the great stone face on the hill between Sonora and Ray, disappeared one day in a thunder of dynamite. Bulldozers and shovels crawled all over it,” (quoted in Seefeldt, p. 28). The open pit enveloped the three towns. In 1958 some residents of the former communities of Sonora, Ray and Barcelona relocated to Kearny, a planned community created by a real estate developer under contract to Kennecott; others moved to surrounding communities, including Hayden.

In the early 1950’s Kennecott had begun to rid itself of the company towns that surrounded its mining and smelting operations. The cost of operating a company town had become prohibitive; “it was a competing business that drained energy and resources from mining.” In 1954 Kennecott sold its remaining residential communities in the region—the entire town of Hayden and the downtown districts and homes of Ray and Sonora (but not the land beneath them) to John W. Galbreath Development Corporation (Barcelona had already been abandoned) (Seefeldt, p. 7). Galbraith was in the business of purchasing company towns and then redeveloping them as municipal entities, selling off lots and homes to individual residents. Galbreath built the town of Kearny to provide housing for the displaced residents of Ray and Sonora; it was incorporated as an independent municipality in 1959. Galbreath’s company also handled the incorporation of Hayden as an independent municipality in 1958.

In 1962 Kennecott sent eviction notices to the remaining 2700 residents of Ray and Sonora, to be enforced by December 1965. Kearny was still under construction, with 216 homes available. This was not enough to house the dislocated population, and some Sonoran families complained that they could not afford to buy one of the newly built Kearny homes (Seefeldt, pp. 29-30). In 1963 the Ray business district was destroyed. By 1965 an estimated 2,712 people had moved to Kearny, Hayden, and other mining communities in the region. In 1982 Kennecott closed its Hayden smelter, and in 1986 ASARCO purchased Kennecott’s Ray mine, consolidating its control over the region.

Although the towns of Ray, Barcelona and Sonora have been engulfed by the vast open-pit Ray mine, memories of tight-knit community life persist. One former resident remembers what it was like to grow up in Sonora:

“When I was a kid, you could be on the other side of town doing something wrong and any older woman could scold you and you had to mind them. Everybody was your mother. You respected all the people there. When anybody was in some kind of trouble, all the people would pick up as much funds as necessary and help them.” (Susan Wootton, Copper Basin News, Sept. 1988)

Shaped by the serious and sometimes unforgiving demands of hard labor, industrial combat and deep patterns of race/class division, the Hayden-Ray area was, and continues to be, central to the production of copper in Arizona. Hayden, Winkleman and Kearny have maintained close community ties and pride in their labor/union traditions even while enduring dislocation and changes brought on by shifting patterns of ownership and corporate functioning.

In Search of Hayden’s Past

If you spend time in the Hayden Library, a nerve center of the community, you’ll find all sorts of local documents and stories, which hold the collective history, and memory of the community. We found a high school student paper, which offered a look back at the town’s legacy and divided racial past.

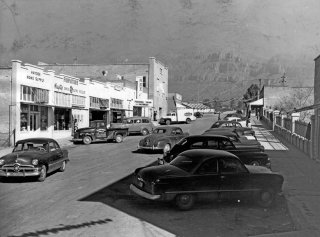

Hayden life during its glory days was a beautiful mining town torn between two races. One race, which was richer than the other were called the Anglos, or the white people, the others were Mexicans. Hayden was the rich part of town; it contained a strip full of buildings, including a theater. San Miguel and San Pedro were the poor part of town where all the Mexicans lived. The Mexicans who lived in San Miguel were called ‘Sorumartos’ because they were more Indian and short. The Hispanics who lived in San Pedro were from different parts of Mexico and more Spaniard looking. Presently there are few Anglos living in the area, almost all the buildings are dead, yet each holds stories of the Mexicans’ troubles with racism during Hayden’s glory years. (“Hayden, What Life Was Like During Its Glory Days,” April 16, 2002)

Our young high school historian goes on to draw on local memories and observations – the segregated class rooms, the local branch of the KKK burning crosses in the 1950s, “the nice pool” open only to Anglos. Despite all of this, in 1958, Hayden celebrated its incorporation as an independent township by proudly receiving the All-American City designation of the National Municipal League. Hayden has endured much in its 100-plus years—and families, some of whom can trace their legacy back four generations–remember the price they have paid, even while celebrating the strengths and relationships engendered by small-town community life.

Frank Amado is a retired school teacher, athletic coach and musician. The Amado family can trace its heritage in Southern Arizona back to the 1700’s. Frank’s father was brought to the community as a young child; he settled in San Pedro amidst a thriving Hispanic community, and raised his family there. Frank has many vivid and affectionate memories of San Pedro:

I didn’t watch a TV until I was 13 years old. So the radio was the main attraction for us. You know…listen to music and playing games around the neighborhood…we skated…There used to be a lot of donkeys…and we rode them as entertainment. Rode them to the river, rode them to the school sometimes.

Frank describes San Pedro as a thriving community.

The pool hall was the main activity of the miners…pool playing, card playing… everybody gathered, that was the gathering place for the miners. Miners: they work hard and they play hard!

Frank attended junior college in Eastern Arizona and then entered the military. When he completed his service he returned to college on the GI bill and graduated from Arizona State University. This prepared him to return to his home town to teach social studies and coach sports at the local junior high school.

Frank’s father and grandfather worked in the copper industry at a time when there was systematic discrimination against Mexican and Mexican-American workers.

The Mexican workers and the Anglo workers did the same type of work, but they got paid differently. The Anglos got a dollar more for doing the same work and the same amount of work. And that’s the way the company policy was..in those times discrimination was very strong.

After World War II many of the old segregated patterns that separated Anglo and Hispanic residents in Hayden/San Pedro collapsed.

After the Second World War when the soldiers came back, they put their foot down and said, “Enough is enough.” They fought for their rights…and things started getting better.

The movie theater was desegregated. By the late 1960’s Hispanics were able to buy houses in formerly all-white parts of town. Hispanic workers began to receive equal wages with their Anglo counterparts and some were offered advancement into managerial situations. At the same time Anglos gradually began to leave Hayden—the white managers who continued to work at the smelter relocated their families and commuted from the expanding municipal areas around Phoenix. Unknown to the community, some patterns of discrimination would persist into the late 1980’s and ‘90s.

In the 1940’s Frank Amado’s father wrote a corrido, celebrating the San Pedro community. During one of our visits to Hayden, Frank sang the corrido for us:

Get the Flash Player to see the wordTube Media Player.

Entrando al San Pedro, ustedes miraran, Las casas tumbadas, las casas tumbadas, Pero no se cayen.

San Pedro lindo, San Pedro lindo, que tu estas, La gente te quiere, la gente te quiere, No olvidaran.

Por eso vienen, por eso vienen, Lejos de aqui. A verte, San Pedro, La gente, San Pedro, Te quiere a ti.

En el año de 1909 este campo empezo. Con gente humilde, con gente humilde Que de Mexico llego.

Ellos se acabaron,y los hijos quedaron, Contentos y orgullosos, contentos y orgullosos Que en San Pedro se crearon.

San Pedro lindo, San Pedro lindo, que tu estas, La gente te quiere, la gente te quiere No te olvidaran.

Por eso vienen, por eso vienen, Lejos de aqui. A verte, San Pedro, La gente, San Pedro, Te quiere a ti.

Attention sirs and ladies to what I am going to recite The San Pedro corrido, the San Pedro corrido I am going to sing for you.

Entering San Pedro you will see Houses that are leaning, houses that are leaning, But they don’t fall.

Beautiful San Pedro,beautiful San Pedro that you are, The people love you, the people love you They will not forget you.

That’s why they come, that’s why they come, From far away. To see you, San Pedro, The people, San Pedro, They love you.

In the year 1909 the town began With humble people, with humble people, Who came from Mexico.

They ended up here, and their children stayed Happy and proud, happy and proud, That in San Pedro they were raised.

Beautiful San Pedro, Beautiful San Pedro that you are, The people love you, the people love you They will not forget you.

That’s why they come, that’s why they come, From far away. To see you, San Pedro, The people, San Pedro, They love you.

Workplace and Environmental Hazards in Hayden

Besides archiving local stories and memories of the community, the Hayden Library also houses artifacts, records and news reports. In particular, old maps and news clippings tell the story of challenging working conditions and the changing landscape.

Since 1910 mine tailings (the first waste products from ore extraction) have been stored in giant mounds called impoundments. According to the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, tailings disposal in this area in the early 20th century occurred at the rate of approximately 4,000 tons per day, increasing to 16,000 tons per day by 1952 and to 21,000 tons per day by 1960.

Over time the tailings mounds have become a pervasive and encroaching hazard. A 1988 article states,

Where the present disposal area in Hayden is now, there used to be farm land with alfalfa fields, cattle, several houses and a general mercantile store… These former sites are now buried under millions of tons of tailings. (Johanna Teer, 1988, pg. 9)

Today, tailings impoundments resemble giant dunes, massed along the side of the road that connects Hayden and Winkleman to the Ray mine In 1972 a slope failure (landslide) measuring 500 feet across, and 30-50 feet deep occurred at one of the impoundments. Other failures have occurred over the years (http://www.azdeq.gov/environ/waste/sps/download/state/asarco.pdf), and many people in the community worry that a driving rainstorm or earthquake would destabilize the huge impoundments. Community members have also complained about Asarco’s unregulated emissions—the state regulates the particulate size of emissions but not the quantities of toxic emissions produced—and they warn of ASARCO’s persistent practice of cranking up the furnaces at night. In the 1980’s and 90’s, as concern about the danger from mine tailings and emissions continued to mount, there was also growing outrage about working conditions–from grim accidents to hazardous exposures on the job.

In 1990 Willie Craig, president of United Steelworkers Local 886 of Hayden conducted an investigation into health monitoring practices at ASARCO. Craig’s damning report, Asarco and Arsenic: The Right to Know, the Right to Live – A Case Study, was not to be found in the Hayden library. Instead we stumbled on it at the Chicano Small Manuscripts section of the Arizona State University Library in Tempe.

A quiet, yet insistent voice from the past, Craig’s report documented serious violations of worker and civil rights. As the report made clear, ASARCO’s national Medical Director, Charles Hine, based in San Francisco, had authored a policy of occupational health apartheid, a policy that created unequal standards of monitoring and protection for Hispanic and Anglo workers. While ASARCO claims that they revoked the policy around the time that Craig’s report was released, it nevertheless represents a remarkable throwback to early and mid-20th century discriminatory and unethical practices, where ethnic identity was used to manage and apportion risk.

Acting on a confidential warning issued by Asarco’s retiring physician, Craig began an investigation into what became known as “the Hispanic factor.” The investigation revealed that ASARCO at Hayden was systematically altering the lung function results of Hispanic workers that were mandated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Craig wrote,

If a Hispanic employee has a pulmonary function of 85% of capacity, when using the Company’s method, this employee is still rated as having 100% of pulmonary function because of the 15% margin the Company has in fact self-imposed upon all Hispanics being tested at the time.

Alarmed by the danger to its members posed by the company’s medical policy, the United Steelworkers contacted Dr. David Parkinson, a respected union physician from New York. Dr. Parkinson’s correspondence with ASARCO’s medical director is included in Craig’s report. In a letter to Hine, Dr. Parkinson confirmed that, “the predicated values in Hispanics were being reduced by 15%.”

Here are some significant excerpts from Craig’s investigation:

1) The lung function tests of Hispanic workers were systematically inflated by 15%.

2) Asarco’s medical director justified the doctored figures by claiming that Hispanic workers had a larger chest capacity than Anglos.

3) According to Craig, “During an OSHA inspection of the Asarco Hayden Plant conducted in 1988 it was found that the working environment of the Hayden Plant violated the present OSHA standard 109 times over. Realistically speaking, Local 886 believes that his figure hasn’t changed for the better, if anything it has either remained basically the same or at times gotten worse in nature.”

4) The x-rays taken of Hayden workers were often unreadable, perhaps due to faulty, poorly maintained equipment. Also, x-rays were not properly recorded or communicated to workers.

5) The pulmonary function testing equipment at Hayden had not been properly calibrated for several years.

6) The report challenged the company and its medical staff, concluding: “Asarco and other parties have conspired with a sense of intense maliciousness to distort, misrepresent and mislead its employees, the public sector and various state and federal agencies [withholding] important information needed to protect the work force and the surrounding communities from excessive arsenic exposure. Asarco and perhaps other parties have conspired jointly to look the other way and protect their interest regarding legal, moral and ethical responsibilities and have done so for a number of years.”

In April 1990 Local 886 reported on the “Hispanic Factor” in its publication, The Slag Dump. The Slag Dump, a member of the USWA Press Association, ran an extensive story to broadcast concerns to members in the region.

The Company has basically formed their own standards…Hispanics at the Hayden plant can suffer a 15% loss in lung function with no apparent ill effect…This is a direct form of racial discrimination and thus is viewed as a violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act by this local…The majority of those who work at the Hayden Plant are of Hispanic origin. When one compares other management techniques that have been imposed by management at the Hayden plant, such a discovery is not totally unthinkable. It is time that the community, the state and the nation become aware of the problems the copper workers face today.

The Asarco and Arsenic document, a compilation of reports, data, testimony, analysis and ethical argument is a very forceful and significant piece of work. It stands as the courageous, determined effort of a rank-and-file unionist, in connection with consulting physicians, to bring to light seriously disturbing practices. Soon after the Arizona Republic published an article about Willie Craig’s report, he became the target of company’s threats and efforts to silence him. The USWA supported Craig in filing charges of retaliation against ASARCO through OSHA provisions, but it’s not entirely clear how the situation was resolved. Local folks tell us that Willie Craig moved away. The company claims the Hispanic Factor policy was revoked. Unfortunately, the paper trail on ASARCO’s medical practices is not complete, and pressing questions remain. For instance, were the lung function tests of the primarily Hispanic workers at ASARCO’s Arizona mines and El Paso, Texas smelter also altered? The workers have the right to know.

Willie Craig’s report reminds us that past practices that were discriminatory and undermining of health may not be truly past. The Hispanic factor bears similarities to the infamous Tuskegee practice of NOT treating known African American syphilis patients from the 1940s to 1970s. An identifiable risk, with clear advisories for public health protections, was not attended to because of the ethnic identity of the people involved. Workplace safety, health and environment committees must remain ever vigilant and mindful of corporate policies, records, reports, data, referrals and professional consultations, and their potential to create profound impacts on worker health and the community environment.

Hayden Today

Today the community of Hayden numbers about 800 people, housed within approximately one square mile. Although the smelter is in full production, the community is experiencing hard times. In 2009 the median household income was $26,797, $22,000 less than the state median. The population has declined from 892 in 2000 to 808 in 2009. 85% of Hayden’s residents are Hispanic. Only 3.5% of Hayden’s adult population has attended college, and the unemployment rate in 2009 was 14%. (http://www.city-data.com/city/Hayden-Arizona.html) Hayden’s downtown consists of two blocks of boarded-up stores. The theater went out of business long ago; the schools were relocated to Winkleman, and the nearest grocery store is in Kearny. Families worry that the bleak physical and economic landscape won’t be enough to keep their children in Hayden. In 2008 we recorded a discussion with high school students from Hayden, San Pedro and Winkleman, and asked them about their perceptions of the community.

Get the Flash Player to see the wordTube Media Player.

Smelter Site is of Growing Concern: Community Response, Agency Moves

The Hayden/Winkelman community is caught in the classic “jobs-versus health and safety“ no-win situation. They need both, but most have felt cornered and without options. Even those who don’t work at ASARCO are dependent on the company to support the economy of the struggling community. Workers at the school district or the mini-mart know they cannot survive economically without ASARCO. This makes it difficult for community members to raise concerns about company policies. Still, questions about impacts on worker and family health and safety have haunted Hayden for decades.

While concerns about worker and community safety and health at ASARCO are not new, there is widespread agreement that conditions grew significantly worse when Grupo Mexico took over the operation of ASARCO in 2002. In July 2006 at a Steelworkers training in Phoenix, workers told us of dangerous conditions at the Hayden smelter caused by deteriorating facilities and equipment, poor training for new workers and inadequate safety and lockout procedures. The roof of a building had just collapsed; the company had ignored warnings that a collapse was likely to happen. A member of USW Local 886, described “bad structural steel conditions” in the plant (names of the workers have been withheld).

The steel is actually rotted to where it might have started out as 3/8 of an inch thick or half an inch thick or 5/8 of an inch thick. Now it’s down to 1/16th of an inch. In some places, it’s like paper. And these are structural steel that supports the main building frame…We’ve reported this to various supervisors, but it seems to fall on deaf ears.

The workers described a near-fatal accident in which two new employees were hit by cranes and seriously injured.

These guys had barely made a 90-day probation period…they’re going up there green…if you put your hand in the wrong place, step in the wrong place, it could be your life, a hand, you know? These poor guys are lucky they’re alive.

Two other workers were badly burned in an explosion; another was electrocuted; still another was decapitated by a conveyor belt.

In the morning…when I leave for work I’m not sure whether I’m going to come back at the end of the day because I don’t know what’s in store for me…And we leave everyday hoping to come back the same way we left. You know, intact.”

In 1994 Hayden’s smelter was #6 in the nation for TRI (Toxic Release Inventory) releases, “among the top 20 polluters nationwide” (Phoenix New Times, 12/3/98). It has been difficult getting agencies to respond to safety and health concerns. 1990’s state government studies found no conclusive links between exposures and cancer. Asarco funded an Arizona Department of Health Services study, asserting it would “confirm … there is little if no impact from the plant on the community” (Phoenix New Times, 4/29/99). Yet home-buyers had to sign waivers releasing previous owners from liability for hazardous dust exposures.

Despite the studies, Hayden residents have persistent concerns about the risks to community health and they have pointed out the frequency of cancer, pulmonary illness, heart disease, and miscarriages in their community. The level of community concern became intense enough for 253 residents to organize a multi-million-dollar lawsuit against ASARCO. The suit languished in court but was eventually bundled into the Asarco bankruptcy process. The bankruptcy court awarded $4.8 million to the claimants, with over 60% going for legal fees. Like other communities who attempted the lawsuit strategy, many felt betrayed and disappointed at the pittance they’ve been awarded.

With little regional or state support, some residents hoped that the EPA would carry out its own independent investigation. By 2004, the EPA was conducting tests in Hayden/Winkelman under its Emergency Response provision, despite community skepticism and unwelcoming responses from company officials and state and local authorities. Even the union hesitated, concerned about the potential loss of jobs and about bringing negative attention to an already beleaguered and vulnerable community. Still EPA Region 9 staff labored on with its investigation, spurred by the growing evidence of serious hazard. Over 1000 soil samples were collected. Water and air samples were also taken.

Starting in 2007, EPA staff held public meetings in Hayden and Winkleman to inform the community about its test results, which documented significantly elevated levels of arsenic, lead, copper, cadmium and chromium in air and soil.

These concentrations indicate the arsenic in Hayden air is about 60 times above what would be expected in an area unaffected by smelting activities.”(Asarco Hayden Plant Site, September 2008, pg.2 )

The EPA pointed to ASARCO as the party responsible for the contamination. The agency was prepared to declare Hayden a Superfund site and place it on the National Priorities List, but it encountered opposition from company, public and union leaders, as well as from community residents. ASARCO argued that NPL listing was unnecessary and that the company could manage the cleanup without federal interference—although ASARCO officials also questioned whether their smelter was, in fact, responsible for the toxic levels of contaminants that had been found. The Steelworkers expressed their concern that NPL listing would depress real estate values and cripple economic development in Hayden; they also argued that the bankruptcy–which had separated ASARCO from Grupo Mexico and engineered a favorable contract between the company and the union–made ASARCO a more trustworthy community partner. Facing widespread opposition to Superfund listing, the EPA forged a compromise agreement with the state and ASARCO: the company would assume responsibility for cleanup of area soils, but the EPA would monitor the cleanup and continue to inform community residents about potential hazards.

At a July 2009 meeting in Hayden, the EPA staff delivered more detailed reports. About 650 properties in the two adjoining towns had been sampled, with 250 requiring cleanup due to excessive levels of arsenic, copper and lead. One of Hayden’s few parks, adjoining the Hayden public library, on the edge of the smelter property, had been cleaned, and supplied with new grass and playground equipment. The work moves along, although at a slow pace, with continuing monitoring and selective cleanup of area properties.

Today 840 people live in Hayden, 435 in Winkleman. The tiny communities continue to be haunted by a past that was marked by unjust, discriminatory practices, a dramatic lack of transparency and a very weak display of commitment to public safety and health by Arizona government agencies. The research and organizing efforts that may eventually improve the quality of life in Hayden and Winkleman are due entirely to the efforts of dedicated workers, courageous community members and a few committed EPA staff. Yet Hayden, the last smelter site in the US, a town built to provide the nation with one of its primary industrial resources, should be receiving widespread attention. The workers and residents of Hayden and Winkleman deserve respect and support from labor and environmental advocates—for their efforts on behalf of workplace and environmental justice and because of their legitimate needs for community and worker health and safety.

Our focus in this project has been on the mining/smelting towns of Hayden and Winkleman. But the impacts of Asarco’s operation are felt around the state. Two Indian tribes are named as creditors in the bankruptcy: O’odham tribal lands have been damaged by the Asarco Mission Complex; and near Casa Grande, on the Gila River Indian Reservation, the Sacaton mine is notorious for its blowing dust and particulates. As part of its bankruptcy settlement, ASARCO funds will help enhance a public safety facility in Casa Grande. Meanwhile there is renewed concern about wind-blown dust near other ASARCO mines and smelters, including the Hayden smelter. In January 2010, Pima County and EPA officials spoke to concerned residents. ASARCO faced some stiff fines, but Tom Aldrich, ASARCO’s Vice President for Environmental Affairs, reassured the assembled crowd that “across the board these [dusts] are very low in metals, about what you’d expect here, comparable to the background levels in soils.” Meanwhile, news reports indicate that state soil scientists have a re-energized interest in dust-born metals and are looking further into mine contaminants across the state. The search for knowledge goes on in the land where copper continues to reign.

Sources:

Arsenic and Asarco: The Right to Know, the Right to Live – A Case Study, prepared by the Investigations Committee, William Craig, United Steelworkers Local 886; 1990.

Bustamente, Antonio. “Mexican Mine Worker Communities in Arizona: Spatial and Social Impacts of Arizona’s Copper Mining,” Estudios Sociales, v. 5, #10, 1995, pgs. 27-54.

Center for Health, Environment and Justice, Superfund: In the Eye of the Storm, March 2009. pgs. 32-33: Arizona site: Hayden-Winkelman: “Fighting the Long Fight for Health in Copper Country”

Craig, Willie. “Is Asarco Practicing Racial Discrimination?” The Slag Dump, April 1990; pgs 1 – 3.

Don’t Waste Arizona, an environmental organization that has lent technical support to the Hayden community and publicized their story; information, films, photos. http://www.dontwastearizona.org/

“EPA to discuss sample program tonight, tomorrow,” Copper Basin News, January 9, 2008

“EPA Releases “ASARCO Hayden Plant Investigation Results,” EPA Asarco Hayden Plant Site, September 2008.

“Public Meeting: Residential Yard Cleanup and Future Activities,” EPA Asarco Hayden Plant Site, July 2009.

“Asarco Hayden Plant”: description, history, potentially responsible parties, documents, reports, contacts, community involvement. This site provides detailed profiles of mine/smelter ownership and operations. http://www.epa.gov/region9/AsarcoHaydenPlant

Franchine, Philip. “Mine dust not dangerous, residents told,” Green Valley News, January 30, 2010

Interview with Frank Amado, conducted by Anne Fischel, Lin Nelson and John Regan. Hayden, Arizona, January 2008.

Interview with Student Council members, conducted by Anne Fischel, Lin Nelson and John Regan. Winkleman, Arizona, January 2008.

Lopez, Leonor. Forever Sonora, Ray, Barcelona: A Labor of Love. n.d.

“New Casa Grande Public Safety Facility Enhanced through Asarco Donation,”

www.trivalleycentral.com August 19, 2010

Parrish, Michael. Mexican Workers, Progressives and Copper: The Failure of Industrial Democracy in Arizona during the Wilson Years, Chicano Research Publications, 1979.

Rosenblum, Jonathon. Copper Crucible: How the Arizona Miners Strike of 1983 Recast Labor-Management Relations in America, Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 1995.

Seefeldt, Douglas. “Creating Kearny: Forging a Historical Identity for a Central Arizona Mining Community,” Faculty Publications, Department of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2005, http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=historyfacpub

Sicotte, Diane. “Profit, Pollution and Racism: The Development of Environmental Injustice in a Copper Smelter Town,” Human Ecology Review, v. 16, #2, 2009, pgs. 141-150.

Teer, Johanna Seeley, “Hayden Takes Steps to Have Its Own Identity,” Copper Basin News, 1988 series.

“What’s in the Smoke? A Breathers’ Guide to Douglas Smelter Pollution,” The Cochise Smelter Study Group, Bisbee AZ 1982

Wootton, Susan. “Sonora Querida! Beloved Sonora,” Copper Basin News, 1988.

Sonora Photographs from the collection of Frankie and Chuy Olmos, Kearny, Arizona.

Useful Documents:

Public Health Assessment, ASARCO Hayden Smelter Site

DMMR – Arizona Mining Update 1999 – Jul 2000

Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Lower San Pedro Basin, An ADEQ 2000 Baseline Study

EPA, ASARCO HAYDEN SMELTER SITE – Mar 2007