Plumes of toxic, smog-causing chemicals from Barnett Shale natural-gas operations are so common that inspectors find them nearly every time they look, a Dallas Morning News examination of government records shows.

What's more, the inspectors have rarely looked.

Hundreds of pages of documents obtained by The News under federal and state open-records laws, plus other reports and studies, reveal a pattern of emissions of toxic compounds, often including cancer-causing benzene, from Barnett Shale facilities.

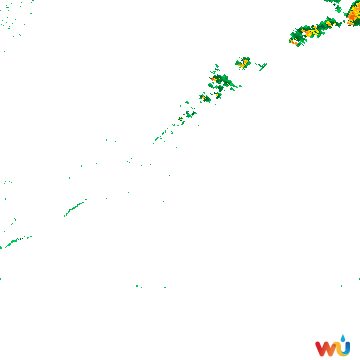

More than 90 percent of the gas-processing plants, compressor stations and wells that agencies have examined with leak-detecting infrared cameras since 2007 were lofting otherwise invisible plumes of chemicals. In the most recent surveillance late last year, every facility checked was emitting pollution.

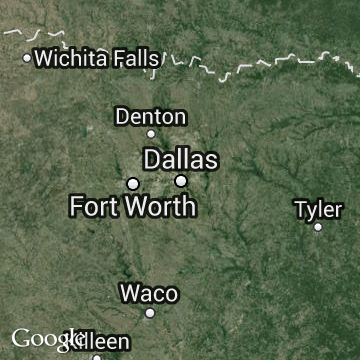

Many were near homes, emblematic of drilling's spread into North Texas urban areas. One was next to the University of Texas at Arlington. Another was just over the right-field fence of a Decatur softball field.

Gas operators say most pollution the cameras caught was routine and legal, requiring no repairs. Even authorized emissions face new scrutiny as state and federal regulators cope with drilling's impact in Tarrant County and areas to its north, west and south.

The infrared cameras - the newest ones cost $106,200 each, including lenses, plus $1,000 per user for training - are potentially powerful weapons against environmental violators and sloppy operators, revealing problems that neither inspectors, neighbors nor companies can see. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has two new ones and six older models.

State and federal agencies have aimed infrared cameras at only a tiny fraction of the 13,000 natural-gas wells and support facilities that have appeared across North Texas since 2005.

The fact that regulators find chemicals rising virtually every time they aim the camera suggests that a comprehensive search might reveal thousands of releases of volatile organic compounds into the air - some authorized, some not.

Months after companies told the TCEQ that they had fixed any problems the state's cameras detected, other scientists found chemicals wafting into the atmosphere.

"We found emissions from wells, condensate tanks, compressor stations" - just about every component of the Barnett Shale production system, said Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist helping the Denton County town of Dish monitor air pollution.

"There are toxic air emissions being released by the majority of the facilities that we have looked at."

Texas officials acknowledge that just about every Barnett Shale installation emits invisible air pollution.

"When we aim the camera at any one of these facilities, be it a compressor station or a condensate tank battery, we are going to see some emissions," said John Sadlier, the TCEQ's deputy director for enforcement.

Those are usually normal and expected emissions from routine operations, Sadlier said. He called the findings "no different from shooting [infrared video of] an idling car. You expect to see some emissions from the tailpipe."

The car comparison might be apt. Last year, Dr. Al Armendariz, then an environmental engineering professor at Southern Methodist University, concluded that Barnett Shale operations were emitting more smog-causing pollution than all the cars, trucks, buses and major airports in the Dallas-Fort Worth region.

Armendariz is now the Environmental Protection Agency's regional administrator, chief federal environmental enforcer in Texas and four adjacent states.

He said the EPA will enforce the Clean Air Act and follow congressional and judicial mandates, developing rules as needed while pursuing voluntary partnerships with industry.

"If we see a violation of the act," Armendariz said, "we will come forward aggressively."

Latest study

After Dish presented a consultant's study documenting high benzene levels from gas operations near homes, the TCEQ launched its own investigation.

Agency crews took conventional photos and infrared video at 40 Barnett Shale facilities in late August and mid-October.

The commission's approach is aimed at "collecting data maybe that we did not have before," said executive director Mark Vickery. "And that's getting out there with our mobile monitors, being responsive to the citizens, getting out sooner, responding faster."

Lacking a central inventory of all Barnett Shale equipment, some crews had trouble identifying the facilities they were examining, agency correspondence with gas operators shows. Sometimes companies had to correct presumptions about who owned a leaking tank.

The TCEQ intends to inventory all of the oil and gas facilities it regulates, said state Sen. Wendy Davis, D-Fort Worth. "Until we know where all the sources are, we certainly can't get a handle on what these sources are emitting," Davis said.

The state saw emissions at all 40 installations it checked last year. While most appeared routine and authorized, Sadlier said about one in five was clearly a leak from a stuck or broken valve or an open hatch on a condensate tank.

The tanks collect liquid hydrocarbons that often accompany natural gas. They have hatches for loading and unloading and relief valves that open when pressure rises.

The tanks are key Barnett Shale pollution sources but are subject to minimal state regulation.

Texas officials say companies quickly stopped leaks that the infrared images revealed. Some companies expressed surprise at the discoveries.

Dallas-based Crosstex Energy Services, which had six facilities identified in the videos, "was unaware of potential emissions that are suggested by the plumes depicted in the videos," Sean Atkins, the company's environmental safety and health director, wrote to the TCEQ on Dec. 15.

"The company found the videos to be very helpful," Atkins wrote, in finding leaks and designing new procedures.

Other companies told the TCEQ that the emissions were from normal operations, so they planned no changes.

That was the case with gas equipment near UTA and a neighborhood. TCEQ videos showed emissions from a tank vent stack on Aug. 25 and Oct. 10. On that second date, they also saw emissions from other equipment.

DFW Midstream Services, owned by an Atlanta firm and Dallas' Energy Future Holdings, which owns TXU, Oncor and Luminant, said the emissions at its UTA facility were routine and expected.

"DFW Midstream works actively to minimize emissions, keeping actual releases of organic compounds well below the TCEQ-allowable level for this type of facility," spokeswoman Ashley Monts told The News in an e-mail. "As such, there have been no violations of the authorized limits at our facilities."

On Aug. 27, at another company's gas-treating plant in the Denton County town of Justin, state inspectors checked a tall stack they called an unlit burner, seemingly idle against an afternoon sky. Infrared video showed chemicals pouring into the air.

On Oct. 11, 45 days later, "emissions from the unlit flare were again observed and documented," inspectors wrote.

By then, Kinder Morgan Treating LP had acquired the plant from Crosstex. Kinder Morgan told the TCEQ that the unlit flare was actually a vent stack, or emissions point, and that the emissions did not mark a leak.

On a TCEQ questionnaire that asked for an "explanation as to how you plan to fix or have fixed the observed emissions," Kinder Morgan wrote that it would take no action because the plumes were "authorized ... and expected."

"No leaks were identified," company spokesman Joe Hollier told The News in an e-mail. "Therefore, no repairs were required."

'Find and fix'

So far, Barnett Shale companies have paid no price for leaks or excessive emissions. The TCEQ followed a policy of "find and fix" that encouraged voluntary repairs with no enforcement.

Executive director Vickery said the commission decided to delay using orders, fines and punishment because many operators might have been unfamiliar with details of the rules.

"It was obvious that many of the oil and gas producers in the Barnett Shale are not people we work with on a day-to-day basis," he said "The end goal in our effort was compliance ... but because this is new to them, the opportunity was there for them to get into compliance on a voluntary basis."

TCEQ documents list 21 companies as owners or operators of the 40 facilities examined with infrared cameras. Two or three appear to be small companies.

The rest are among the nation's largest independent companies, most with decades of gas production or pipeline experience across multiple states, or subsidiaries or joint ventures of some of the world's biggest corporations, including ExxonMobil and Conoco Phillips.

"These are not babes in the woods who are new to regulation," said Esther McElfish, president of the Fort Worth-based North Central Texas Communities Alliance, a group seeking tighter rules on drilling. "They have a very clear understanding that they are subject to monitoring and regulation."

"Find and fix" is over, Vickery said, and violators now face enforcement. "That was enough time for them to be able to get out there and turn a valve and close a hatch," he said.

It is apparent, however, that not all Barnett Shale companies have used the grace period to launch voluntary, systemwide changes.

"No, everybody has not," said Sadlier. "And that's why you're starting to see the enforcement actions that are gearing up now."

Repeated problems

Some companies already knew infrared imagery's potential as an enforcement tool.

On Aug. 29, 2007, EPA inspectors used an infrared camera at a Targa North Texas LP gas-processing plant near Chico, in Wise County. They discovered a leaking tank hatch and 13 leaking valves on tanks, a pump, pipes and a cryogenic unit, a super-cold refrigerator for gas processing.

Five cryogenic unit valves were leaking large amounts of chemicals. "These valves were not identified as leakers in any of the facility's VOC [volatile organic compounds] monitoring reports," an EPA inspector wrote.

In a federal settlement completed Sept. 29, 2009, Targa paid a civil penalty of $28,737 based on the five cryogenic unit valves but admitted no violations. The company also agreed to replace tanks hatches at six plants.

As Targa was settling its EPA case, state inspectors found leaks at its Bryan compressor station, also in Wise County. TCEQ infrared videos taken on Aug. 26, Oct. 11 and Oct. 14, 2009, showed emissions from tank rooftops or open valves.

In January, the state said the plant, 150 yards from several homes, had been a source of worrisome benzene levels. Before Targa repaired that plant, airborne benzene levels were 1,100 parts per billion, the TCEQ said.

That is six times the amount that the TCEQ says could cause health problems with just short exposure. It is 786 times the amount the agency says could cause problems with lifelong exposure.

After repairs, the benzene level dropped to 0.21 ppb, a level the state considers safe.

Joe Bob Perkins, president of Houston-based Targa Resources, Targa North Texas LP's parent, did not return phone calls.

In a Dec. 11 letter to the TCEQ, a Targa assistant vice president, Jessica L. Keiser, said the company "takes its environmental obligations very seriously" and acted immediately to fix the leaks the state found.

"Targa North Texas, like all of the companies in the Targa corporate family, is committed to meeting or exceeding the commission's expectations with respect to environmental compliance in the operation of not only its Bryan Compressor Station, but at all of its operations in North Texas," Keiser wrote.

New scrutiny

Barnett Shale operations are in the spotlight at both the TCEQ and the EPA. The TCEQ's Vickery said the state needs more air pollution monitors - costly but important, he said. The commission also is adding inspectors and considering rule changes.

The EPA's Armendariz said EPA enforcement is also possible. Chronically broken or stuck valves, pipes or tank hatch covers aren't allowed under federal law even if emissions stay within authorized limits, he said.

EPA enforcement officials are also studying whether some Barnett Shale facilities should be regulated as major pollution sources. That brings more scrutiny that considers, for example, not only routine emissions but also the higher ones - sometimes 100 times higher - during startup and shutdown.

Armendariz said new EPA air-emissions standards for the oil and gas industry, a much tighter standard on ozone or smog, and other measures will reduce pollution in North Texas.

"Our agency will continue to recognize the benefits of natural gas over other fossil fuels," he said, "but will simultaneously strive to make sure that our other valuable natural resources in North Texas are protected."

To post a comment, log into your chosen social network and then add your comment below. Your comments are subject to our Terms of Service and the privacy policy and terms of service of your social network. If you do not want to comment with a social network, please consider writing a letter to the editor.