| oiled bird/ US Fish & Wildlife Service |

Pepper Trail may be the only full-time forensic

ornithologist. He works for the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Lab in

Ashland, Oregon. On November 3 he visited the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to talk about

the sort of work he does.

Trail documents evidence of crimes against birds. That can

include anything from smuggling endangered species to trade in feathered craft

items. One of the most common kinds of evidence he gets – accounting for a

quarter to a third of all his cases – is oiled birds.

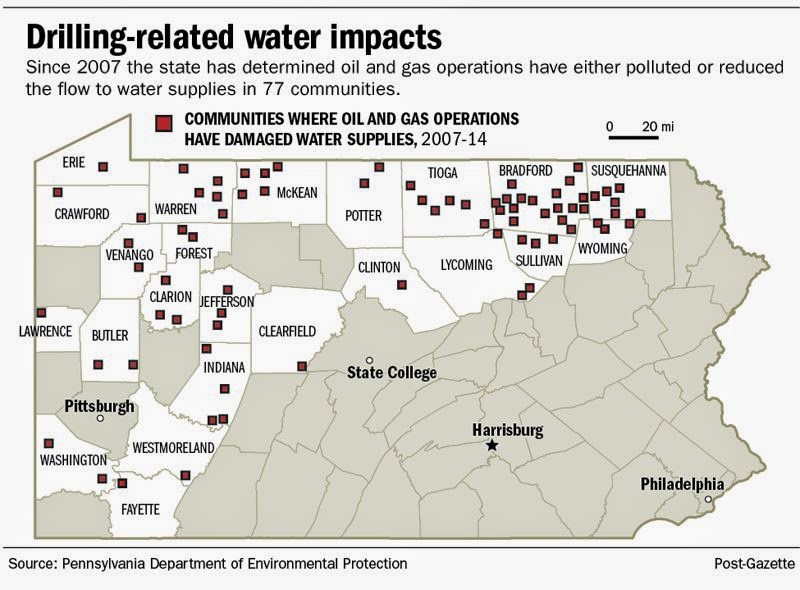

These birds often come from oil pits and waste pits located

at drilling sites, Trail said. Companies are supposed to make their waste pits inaccessible

to birds, but in most cases the their attempts fall far short of the law. Some

look like wetlands, with oily water spread over reedy areas, while others are

well-defined rectangular ponds. Both attract birds.

Trail doesn’t visit drilling sites, so he can’t say exactly where

the birds are coming from or whether the driller is fracking for gas or oil.

It’s the job of field investigators to fish dead birds from the oily depths and

send them in. Trail’s job is to clean the feathers – tail feathers are best, he

says – and look for distinguishing characteristics. So he washes them with

solvent, gives them a rinse and then dries them off with a hair-drier.

Waterfowl aren’t the only birds attracted to gas and oil

waste pits. Trail has identified 172 species, including mocking bird, barn owl,

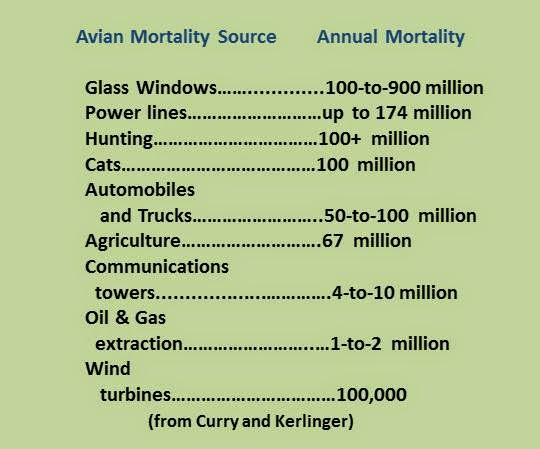

lark buntings and even roadrunners. “The mortality due to gas and oil pits is

in the range of 500,000 to a million every year,” he said. To put that in

perspective, the Exxon-Valdez oil spill killed 250,000 to 300,000 birds. Wind turbines account for about 100,000 bird deaths each year.

“This is some of the

most important work we do,” said Trail. “Not because the fines are high, but

because we can compel the companies to clean up their pits.”

| flags don't adequately protect birds from waste pits |

The current strategy of surrounding the pit with chain-link

fence or stringing used-car-lot flags across the surface is totally inadequate.

“The best way to protect birds is to pump out the pits and inject the fluids

into storage tanks that are closed,” said Trail, adding that an alternative

would be injecting waste into a geological formation – “if that’s safe.”

Securely netting the pond could work, but too often the netting sags into the

oil.

You can learn more about minimizing risks to migrating birds at oil and gas sites here. This was taken from a longer article in the November 10,

2014 issue of Tompkins Weekly