I was talking to some of my friends about the upcoming election and what it could mean for the politics of the environment. We discussed the prospect of a Republican takeover of the Senate and whether it would make any difference. Which path would they go down? Would a Republican Senate push a package of extreme anti-environmental policies; or would GOP control of both chambers of Congress force them to share in governance and strike bi-partisan agreements?

It was October of 1994. The Republicans won control of Congress the next month. Strangely enough they ended up going down both paths at once, extremism and cooperation. The cooperation produced real legislative successes while the extremist measures actually helped rehabilitate an embattled Democratic president. These are still the two choices available for Republican leaders.

It was a different time twenty years ago. There was an activist conservative base pushing its agenda in the party, but there were also pragmatic Republican conservatives capable of working with the Democratic leadership in Congress and the White House. And there were moderates in the Republican party interested in working with others to get things done.

What the heck happened to the party since?

In the last two decades the face of the Republican Party in the Senate has been entirely redrawn, not only to be more conservative, but also to be more explicitly anti-environmental. The wrong lesson from history for the current leadership would be what Michael Gerson has called the mistake of the mid-term mandate. However, the hard right turn in the party’s environmental politics will make it difficult for them not to leap further in that direction.

But first, let’s consider what happened to the Republican leadership in 1995. For starters, the Congressional Republican leadership joined together to launch some of the most vicious attacks on environmental policy ever. These were based mainly on the Gingrich-Dole regulatory reform sections of the Contract with America, which would have turned back a generation of progress on clean air and water. After passing the House, the bill was stopped in the Senate with the help of a bloc of five Republican moderates that offered a more reasonable reform alternative. And yes, opposition to the more extreme Senate version helped lift President Clinton’s ratings and eventually defeat Bob Dole.

By contrast, even while this political knockdown, drag-out fight dragged on, Senate Republicans were busy working with President Clinton to get two bi-partisan environmental bills signed into law: the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 and the reauthorization of the Safe Drinking Water Act. Republicans such as Senator Kempthorne, a conservative but pragmatic legislator from Idaho, were critical to the success of these bills. This was the last time in nearly two decades that a Congress has improved a major environmental health statute through reauthorization.

So, does history offer hope that in the next Congress there will be a group of reasonable Republicans in the Senate who has learned the right lesson from history and will block extremist proposals while seeking bi-partisan progress on the environment? Not much.

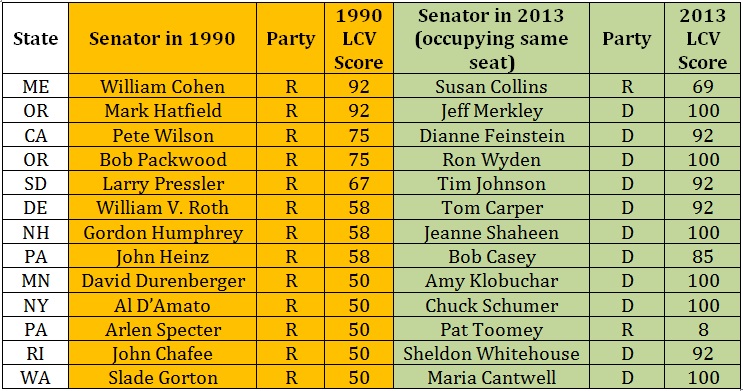

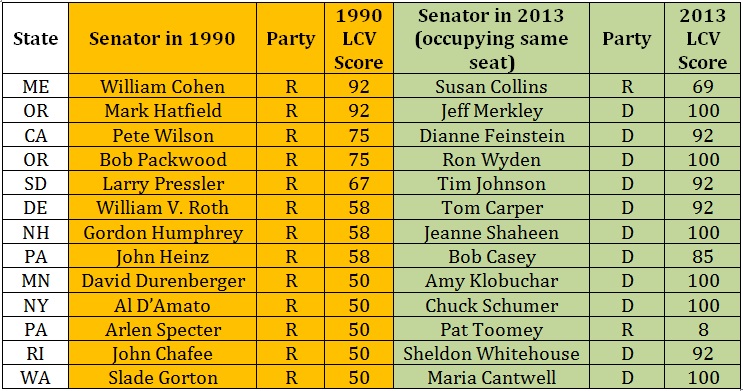

Let’s look at the potential line up now compared to then. In 1990 as in 2014, there were 45 Republicans in the Senate (or independents who caucused with them). However, in 1990 there were also 13 Republicans who could be considered moderates on the environment, i.e. someone who voted for the environment at least half the time as measured by the LCV scorecard. Now there is only one, Susan Collins (see chart below). On a percentage basis the situation in the House is no better. The Congressional Republican moderate on the environment is all but extinct.

But the story doesn’t end there. Moderate Republicans are not only nearly extinct but now Democrats occupy ten of the thirteen seats previously held by Republican moderates. And all of these Democrats have better voting records on the environment than their predecessors. Interestingly, as part of the party’s shift to the right, the two Republicans seats from 1990 still in GOP hands have occupants who voted less reliably for the environment than their predecessor, including Senator Collins. (Note: Senator Specter became a Democrat in 2009.)

1990 Republican Senators with an LCV Score greater than or equal to 50, And Who Held That Same Seat in 2013

Ten Senate seats are a lot to concede to the opposition party in the pursuit of an extremist agenda. The lesson the Republicans should instead take from history is that the party, by moving itself out of the mainstream of the public’s support on environmental issues, has put Republican candidates at a political disadvantage. Even if the party ekes out a Senate majority in a week, it will be harder to hold it in 2016 when numerous Republican senators from blue states are up for re-election.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to look at the incoming Republican leadership and see who except for Collins might make this case to their party. The GOP should rethink its approach on the environment and seek constructive solutions for the sake of the planet. But if not for that reason, then it should really do so for its own sake.