Laws and sanctions go hand in hand. Without sanctions laws and rules are merely suggestions.

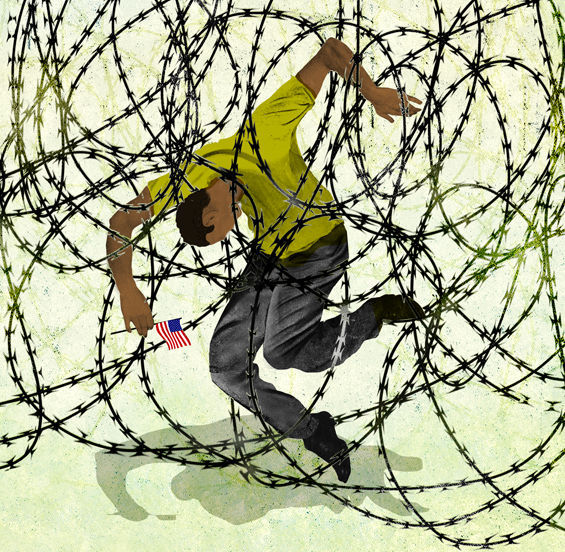

Seeking Asylum in U.S., Immigrants Become Long-Term Detainees Instead

Cecilia Cortes crossed the Tijuana border into San Diego on a Sunday morning this March. The 34-year-old curly-haired brunet, with her 3-year-old son, Jonathan, and her 6-year-old daughter, Alexa — both U.S. citizens — walked a pedestrian bridge into the Otay Mesa Port of Entry station controlled by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Though Cecilia is not an American, she was confident federal agents would allow her to enter the country. She would ask for political asylum, a type of refugee status granted to people who arrive in the United States after fleeing persecution in their homeland.

During a phone interview from his home in Jacksonville, Javier Galvan, Cortes' husband, explains that the couple had spent ten years living in Florida until returning to Cecilia's hometown of Morelia in the state of Michocoan, Mexico, in 2011. "My wife's mother fell ill," he says. "She had no one to take care of her, so we went back."

But soon, the harsh reality of living in Mexico knocked on their door. Shortly after opening a butcher shop, Galvan says members of the Knights Templar drug cartel, which control territories throughout Michocoan, began extorting him for protection money. "If I didn't pay, they threatened to kidnap me and my family," he says. "In Michocoan, you don't take their threats lightly."

Related Stories

Florida Beer: Old Battle Axe IPA From Engine 15 Brewing Co.October 31, 2014

Florida Beer: Old Battle Axe IPA From Engine 15 Brewing Co.October 31, 2014 Silver Airways Begins Flights From Fort Lauderdale to Jacksonville August 20, 2014

Silver Airways Begins Flights From Fort Lauderdale to Jacksonville August 20, 2014 West Palm Beach Flight Diverted After Reclined-Seat Argument September 2, 2014

West Palm Beach Flight Diverted After Reclined-Seat Argument September 2, 2014 Chef Shannon Weiberg of Bash American Bistro on the Early Craft Beer Scene, Southern-Influence, and MoreMarch 17, 2014

Chef Shannon Weiberg of Bash American Bistro on the Early Craft Beer Scene, Southern-Influence, and MoreMarch 17, 2014 Fort Lauderdale Tops List of Florida's Most Dangerous Cities September 18, 2014

Fort Lauderdale Tops List of Florida's Most Dangerous Cities September 18, 2014

More About

Indeed, Galvan relays, his wife witnessed the Knights Templar's bloody handiwork while riding a bus. On the side of the road, the cartel had left six gory heads arranged neatly next to their decapitated bodies. By late 2012, Galvan says he closed the butcher shop and decided it was time to come back to Jacksonville. After three failed attempts to cross the Rio Bravo bordering Mexico and Arizona, Galvan and Cortes found out about the #BringThemHome campaign, an effort by DREAMers' MOMS, a nonprofit that helps undocumented immigrants whose children were born in the United States. Last October, Galvan had crossed the border in Brownsville, Texas, with his 16-year-old son, Javier Jr. "I had no problems," he says. "With the help of the Mexican consulate, we were able to come back to Jacksonville."

But his hopes of being reunited with his wife and two other children were quickly dashed by customs officials in San Diego. Agents slapped handcuffs on Cortes, Galvan says, and separated her from the children. They allowed her to call Galvan so he could have his brother in California pick up Jonathan and Alexa. Officers threw her into a cold, cramped cell before turning her over to Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, which loaded her onto a plane and transported her to an immigrant detention center in San Luis, Arizona, where she is being held indefinitely even though she has no criminal record and has a legitimate claim for asylum. "I haven't been able to fly out to pick up our kids because of economic reasons," Galvan says. "And I don't have any idea if my wife will be released."

The situation is remarkably common. Across the country, vulnerable noncitizens seeking safety and a new beginning are instead funneled into prison-like detainment centers, held indefinitely, and often sent back, sometimes in mass deportations, to the countries where they face threats. When the process goes smoothly, asylum seekers tend to be released in four to six weeks, but many end up imprisoned for months or even years. About 6,000 survivors of torture — exiles from Iran, Myanmar, Syria, and other brutal regimes — were detained while seeking asylum over the past three years, according to a 2013 report by the Center for Victims of Torture.

"It's really tragic," says Amelia Wilson, staff attorney for the American Friends Service Committee, a faith-based organization that aids asylum seekers. "They're fleeing persecution, and many of them have just fled institutions of incarceration in their home country. Through guile or luck or the right contacts, they manage to get out of their country. They come here, and they're promptly detained. They're shocked. They're not criminals. In fact, they're following the legal procedure the government has put in place for them to get protection."

Raising concerns that some people are crying about persecution to gain American residency when really they have nothing to fear, some Republican leaders are now pushing draconian measures that would put even more asylum seekers behind bars. House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte, a Republican from Virginia, has said the asylum system is "exploited by illegal immigrants in order to enter and remain in the United States."

"The tone of immigration politics, even when it comes to asylum seekers, has gotten really vicious," says Alina Das, codirector of the Immigrant Rights Clinic at the New York University School of Law. "People have generally forgotten what it means to be seeking asylum in our country. It's really disturbing, and I think it's a sad commentary on how easily a minority of elected officials can hijack an issue that should really speak to core American values."

In Florida, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has six detention facilities, four of which are operated by local sheriff's offices in Monroe, Glades, Baker, and Wakulla counties. The all-male Krome Detention Center in Miami-Dade is run by ICE. A majority of the 581 detainees at Krome have criminal convictions and orders of deportation. They cannot seek political asylum, but they can appeal to ICE to let them remain in the United States if they can show they will be tortured or even killed if returned to their home country. The sixth facility is the Broward Transition Center, which is run by a private company, the GEO Group. Located in Pompano Beach, most of the 700 detainees at BTC do not have criminal records and are asylum seekers.

Now Trending

Around The Web

-

The Dark Ride

Houston Press

The Dark Ride

Houston Press

-

The False 48

Houston Press

The False 48

Houston Press

-

Guinida: Clear the Lane

OC Weekly

Guinida: Clear the Lane

OC Weekly

New Times on Facebook

-

My Account

Log In

Join -

Connect

Facebook

Twitter

Newsletters

Things To Do App -

Advertising

Contact Us

National

Agency Services

Classified

Infographics

-

Company

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

Site Problems?

Careers