Keystone Pipeline

| Keystone Pipeline System (Operational and Proposed)[1] |

|

|---|---|

Keystone Pipeline Route

|

|

| Location | |

| Country | Canada United States |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Owner | TransCanada |

| Keystone Pipeline (Phase 1) (Done) |

|

|---|---|

| Location | |

| From | Hardisty, Alberta |

| Passes through | Regina, Saskatchewan Steele City, Nebraska |

| To | Wood River, Illinois Patoka, Illinois (end) |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Construction started | Q2 2008 |

| Commissioned | June 2010 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 3,456 km (2,147 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 590 Mbbl/d (~2.9×1010 t/a) |

| Diameter | 30 in (762 mm) |

| Number of pumping stations | 39 |

| Cushing Extension Project (Phase 2) (Done)[1] |

|

|---|---|

| Location | |

| From | Steele City, Nebraska |

| To | Cushing, Oklahoma |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Contractors | WorleyParsons |

| Construction started | 2010 |

| Commissioned | February 2011 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 480 km (300 mi) |

| Diameter | 36 in (914 mm) |

| Number of pumping stations | 4 |

| Cushing Marketlink Project (Phase 3a) (Done)[1] |

|

|---|---|

| Location | |

| From | Cushing, Oklahoma |

| Passes through | Liberty County, Texas |

| To | Nederland, Texas |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Contractors | WorleyParsons |

| Commissioned | January 2014 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 784 km (487 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 700 Mbbl/d (~3.5×1010 t/a) |

| Diameter | 36 in (914 mm) |

| Houston Lateral Project (Phase 3b) (Construction)[1] |

|

|---|---|

| Location | |

| From | Liberty County, Texas |

| To | Houston, Texas |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Contractors | WorleyParsons |

| Construction started | 2014 |

| Expected | 2014 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 76 km (47 mi) |

| Keystone XL Pipeline (Phase 4) (Proposed)[1] |

|

|---|---|

| Location | |

| From | Hardisty, Alberta |

| Passes through | Baker, Montana |

| To | Steele City, Nebraska |

| General information | |

| Type | Crude oil |

| Contractors | WorleyParsons |

| Construction started | Unknown |

| Expected | Unknown |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 1,897 km (1,179 mi) |

| Diameter | 36 in (914 mm) |

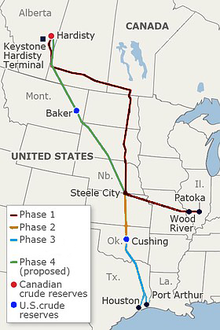

The Keystone Pipeline System is an oil pipeline system in Canada and the United States. It runs from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin in Alberta, Canada, to refineries in the United States in Steele City, Nebraska; Wood River and Patoka, Illinois; and the Gulf Coast of Texas.[notes 1][2] In addition to the synthetic crude oil (syncrude) and diluted bitumen (dilbit) from the oil sands of Canada, it also carries light crude oil from the Williston Basin (Bakken) region in Montana and North Dakota.[2]

Three phases of the project are in operation, and the fourth is awaiting U.S. government approval. If completed, the Keystone Pipeline System would consist of the completed 2,151-mile (3,462 km) Keystone Pipeline (Phases I and II), Keystone Gulf Coast Expansion (Phase III), and the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline Project (Phase IV). Phase I, delivering oil from Hardisty, Alberta, to Steele City, Wood River, and Patoka, was completed in the summer of 2010. Phase II, the Keystone-Cushing extension, was completed in February 2011 with the pipeline from Steele City to storage and distribution facilities at Cushing, Oklahoma.[3] These two phases have the capacity to deliver up to 590,000 barrels per day (94,000 m3/d) of oil into the Mid-West refineries.[3] Phase III, the Gulf Coast Extension, which was opened in January 2014, has capacity up to 700,000 barrels per day (110,000 m3/d).[4] The proposed Phase IV, would begin in Hardisty, Alberta, and extend to Steele City, essentially replacing the existing phase I pipeline.[5]

The Keystone XL proposal faces criticism from environmentalists and some members of the United States Congress. In January 2012, President Barack Obama rejected the application amid protests about the pipeline's impact on Nebraska's environmentally sensitive Sand Hills region.[6] TransCanada Corporation changed the original proposed route of Keystone XL to minimize "disturbance of land, water resources and special areas"; the new route was approved by Nebraska Governor Dave Heineman in January 2013.[5] On April 18, 2014 the Obama administration announced that the review of the controversial Keystone XL oil pipeline has been extended indefinitely, pending the result of a legal challenge to a Nebraska pipeline siting law that could change the route. The challenge has been taken up by the State Supreme Court, making it unlikely that the case will be resolved before the November 4, 2014 mid-term United States elections.[7]

Contents

Description[edit]

The Keystone Pipeline system consists of the operational Phase I; Phase II; and Phase III, the Gulf Coast Pipeline Project, and a proposed pipeline expansion segment Phase IV, Keystone XL. Construction of Phase III, from Cushing, Oklahoma, to Nederland, Texas, in the Gulf Coast area, began in August 2012 as an independent economic utility.[notes 2][8] The Phase III was opened on 22 January 2014[4] The Keystone XL Pipeline Project (Phase IV) revised proposal in 2012 consists of a new 36-inch (910 mm) pipeline from Hardisty, Alberta, through Montana and South Dakota to Steele City, Nebraska, to "transport of up to 830,000 barrels per day (132,000 m3/d) of crude oil from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin in Alberta, Canada, and from the Williston Basin (Bakken) region in Montana and North Dakota, primarily to refineries in the Gulf Coast area."[2] After the Keystone XL pipeline segments are completed, American crude oil would enter the XL pipelines at Baker, Montana, on their way to the storage and distribution facilities at Cushing, Oklahoma. Cushing is a major crude oil marketing/refining and pipeline hub.[1][9]

Operating since 2010, the original Keystone Pipeline System is an 3,461-kilometre (2,151 mi) pipeline delivering Canadian crude oil to U.S. Midwest markets and Cushing, Oklahoma. In Canada, the first phase of Keystone involved the conversion of approximately 864 kilometres (537 mi) of existing 36-inch (910 mm) natural gas pipeline in Saskatchewan and Manitoba to crude oil pipeline service. It also included approximately 373 kilometres (232 mi) of new 30-inch (760 mm) diameter pipeline, 16 pump stations and the Keystone Hardisty Terminal.[10]

The U.S. portion of the Keystone Pipeline included 1,744 kilometres (1,084 mi) of new, 30-inch (760 mm) diameter pipeline in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri and Illinois.[10] The pipeline has a minimum ground cover of 4 feet (1.2 m).[11] It also involved construction of 23 pump stations and delivery facilities at Wood River and Patoka, Illinois. In 2011, the second phase of Keystone included a 480-kilometre (298 mi) extension from Steele City, Nebraska, to Cushing, Oklahoma, and 11 new pump stations to increase the capacity of the pipeline from 435,000 to 591,000 barrels per day (69,200 to 94,000 m3/d).[10]

Additional phases (III and IV) have been in construction or discussion since 2011. If completed, the Keystone XL would add 510,000 barrels per day (81,000 m3/d) increasing the total capacity up to 1.1 million barrels per day (170×103 m3/d).[12]

The original Keystone Pipeline cost US$5.2 billion with the Keystone XL expansion slated to cost approximately US$7 billion. The Keystone XL was expected to be completed by 2012–2013, however construction has been overtaken by events.[12]

Ownership[edit]

While the project was originally developed as a partnership between TransCanada and ConocoPhillips, TransCanada is now the sole owner of the Keystone Pipeline System, as TransCanada received regulatory approval on August 12, 2009 to purchase ConocoPhillips' interest.[13]

Certain parties who have agreed to make volume commitments to the Keystone expansion to have the option to acquire up to a combined 15% equity ownership.[12] One of such companies is Valero Energy Corporation.[14]

History[edit]

Keystone Pipeline[edit]

TransCanada Corporation proposed the project on February 9, 2005.[15] In October 2007, the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada asked the Canadian federal government to block regulatory approvals for the pipeline, with union president Dave Coles stating "the Keystone pipeline will exclusively serve US markets, create permanent employment for very few Canadians, reduce our energy security, and hinder investment and job creation in the Canadian energy sector."[16]

The National Energy Board of Canada approved the construction of the Canadian section of the pipeline, including converting a portion of TransCanada's Canadian Mainline gas pipeline to crude oil pipeline, on September 21, 2007.[17] On March 17, 2008, the United States Department of State issued a Presidential Permit authorizing the construction, maintenance and operation of facilities at the United States and Canada border.[18]

On January 22, 2008, ConocoPhillips acquired a 50% stake in the project.[19] On June 17, 2009, TransCanada agreed that they would buy out ConocoPhillips' share in the project and revert to being the sole owner.[13] It took TransCanada more than two years to acquire all the necessary state and federal permits for the pipeline. Construction took another two years.[20] The pipeline, from Hardisty, Alberta, Canada, to Patoka, Illinois, United States, became operational in June 2010.[21]

Keystone XL[edit]

The Keystone XL extension was proposed in 2008.[11] ("XL" stands for "eXport Limited.") The application was filed in September 2008 and the National Energy Board of Canada started hearings in September 2009.[22] On March 11, 2010 the Canadian National Energy Board approved the project.[9][23][24] The South Dakota Public Utilities Commission granted a permit on February 19, 2010.[25]

On July 21, 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency said the draft environmental impact study for Keystone XL was inadequate and should be revised, indicating that the State Department's original report was "unduly narrow" because it did not fully look at oil spill response plans, safety issues and greenhouse gas concerns.[26][27][28] The final environmental impact report was released on August 26, 2011. It stated that the pipeline would pose "no significant impacts" to most resources if environmental protection measures are followed, but it would present "significant adverse effects to certain cultural resources".[29] In September 2011, Cornell ILR Global Labor Institute released the results of the GLI KeystoneXL Report, which evaluated the pipeline's impact on employment, the environment, energy independence, the economy, and other critical areas.[23]

On November 10, 2011, the Department of State postponed a final decision due to necessity "to seek additional information regarding potential alternative routes around the Sand Hills in Nebraska to inform the determination regarding whether issuing a permit for the proposed Keystone XL pipeline is in the national interest".[30] In its response, TransCanada pointed out fourteen different routes for Keystone XL were being studied, eight that impacted Nebraska. They included one potential alternative route in Nebraska that would have avoided the entire Sandhills region and Ogallala Aquifer and six alternatives that would have reduced pipeline mileage crossing the Sandhills or the aquifer.[31][32] On November 22, 2011, the Nebraska legislature passed unanimously two bills with the governor's signature that enacted a compromise agreed upon with the pipeline builder to move the route, and approved up to US$2 million in state funding for an environmental study.[33]

On November 30, 2011, a group of leading Republican senators introduced legislation aimed at forcing the Obama administration to make a decision on the Keystone XL pipeline within 60 days.[34] In December 2011, Congress passed a bill giving the Obama Administration a 60-day deadline to make a decision on the application to build the Keystone XL Pipeline.[30][35] On January 18, 2012, President Obama rejected the application stating that the deadline for the decision had "prevented a full assessment of the pipeline's impact".[30][36] On September 5, 2012, TransCanada submitted an environmental report on the new route in Nebraska, which the company says "based on extensive feedback from Nebraskans, and reflects our shared desire to minimize the disturbance of land and sensitive resources in the state".[37]

In its supplemental environmental impact statement (SEIS) released for public scrutiny in March 2013, the United States Department of State Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, described a number of changes to the original proposals including the shortening of the pipeline to 875 miles (1,408 km); its avoidance of "crossing the NDEQ-identified Sand Hills Region" and "reduction of the length of pipeline crossing the Northern High Plains Aquifer system, which includes the Ogallala formation"; and stated "there would be no significant impacts to most resources along the proposed Project route."[2] In response to a Freedom of Information Act request for route information,[38] the Department of State revealed on June 24, 2013 that "Neither Cardno ENTRIX nor TransCanada ever submitted GIS information to the Department of State, nor was either corporation required to do so." It remains unclear how the Department of State has determined environmental impacts for the project without this essential information. In response to the Department of State's report, which recommended neither acceptance nor rejection, the editor of The New York Times recommended that President Obama, who acknowledges climate change as one of humanity's "most challenging issues", should reject the project, which "even by the State Department's most cautious calculations — can only add to the problem."[39][notes 3]

In April 2013, the EPA challenged the U.S. State Department report's conclusion that the pipeline would not result in greater oil sand production, noting that "while informative, [it] is not based on an updated energy-economic modeling effort."[40][41] Overall, the EPA rated the SEIS with their category "EO-2" (EO for "environmental objections" and 2 for "insufficient information").[42]

May 22, 2013 Republicans in the House of Representatives defended the Northern Route Approval Act, which would allow for congressional approval of the pipeline, on the grounds that the pipeline created jobs and energy independence. If enacted the Northern Route Approval Act would waive the requirement for permits for a foreign company and bypass the need for President Obama's approval, and the debate in the Democrat-controlled U.S. Senate, concerned about serious environmental risks, that could result in the rejection of the pipeline.[43]

On March 22, 2012, Obama endorsed the building of the southern segment (Gulf Coast Extension or Phase III) that begins in Cushing, Oklahoma. The President said in Cushing, Oklahoma, on March 22, "Today, I'm directing my administration to cut through the red tape, break through the bureaucratic hurdles, and make this project a priority, to go ahead and get it done."[44] On January 22, 2014 the Gulf Coast Extension (phase III) was opened.[4]

Original and extended route[edit]

Phase 1[edit]

This 3,456 kilometres (2,147 mi) long pipeline runs from Hardisty, Alberta, to the United States refineries in Wood River, Illinois, and Patoka, Illinois.[45] The Canadian section involves approximately 864 kilometres (537 mi) of pipeline converted from the Canadian Mainline natural gas pipeline and 373 kilometres (232 mi) of new pipeline, pump stations and terminal facilities at Hardisty, Alberta.[46]

The United States section is 2,219 kilometres (1,379 mi) long.[46] It runs through Buchanan, Clinton, Caldwell, Montgomery, Lincoln and St. Charles counties in Missouri, and Nemaha, Brown and Doniphan counties in Kansas before entering Madison County, Illinois.[21] Phase 1 went online in June 2010.

Phase 2[edit]

From Steele City, Nebraska, the 291 miles (468 km) Keystone-Cushing pipeline was routed through Kansas to the oil hub and tank farm in Cushing, Oklahoma, in 2010 and went online in February 2011.[1]

Phase 3a[edit]

This phase, known as Cushing MarketLink, is part of the Keystone XL pipeline. This phase starts from Cushing, Oklahoma, where American-produced oil is added to the pipeline, then it goes south 435 miles (700 km) to a delivery point near terminals in Nederland, Texas, to serve the Port Arthur, Texas, marketplace.[1] Keystone started pumping oil through this section on January 21, 2014.[47]

Phase 3b[edit]

The Houston Lateral Project approximate 47 miles (76 km) pipeline to transport crude oil from the pipeline in Liberty County, Texas to the Houston area.[1][48] Oil producers in the U.S. are pushing for this phase so the glut of oil can be distributed out of the large oil tank farms and distribution center in Cushing, Oklahoma.

Phase 4[edit]

This phase is part of the Keystone XL pipeline and would start from the same area in Alberta, Canada, as the Phase 1 pipeline.[11] The Canadian section would consist of 526 kilometres (327 mi) of new pipeline.[24] It would enter the United States at Morgan, Montana, and travel through Baker, Montana, where American-produced oil would be added to the pipeline, then it would travel through South Dakota and Nebraska, where it would join the existing Keystone pipelines at Steele City, Nebraska.[1] This phase has generated the greatest controversy because of its routing over the top of the Ogallala Aquifer in Nebraska.[49][50][51]

Keystone XL controversies[edit]

Environmental issues[edit]

Different environmental groups, citizens, and politicians have raised concerns about the potential negative impacts of the Keystone XL project.[52][53][54] The main issues are the risk of oil spills along the pipeline, which would traverse highly sensitive terrain, and 17% higher greenhouse gas emissions from the extraction of oil sands compared to extraction of conventional oil.[55][56] According to the book The Pipeline and the Paradigm by social activist Samuel Avery, fully exploiting the tar sands in Alberta would add between 50 and 60 parts per million of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere over the next figure, raising the total to at least 450 ppm, "the likely threshold level at which critical climate feedback loops take effect and runaway global warming begins."[57]

A concern is that a pipeline spill would pollute air and critical water supplies and harm migratory birds and other wildlife.[26] Its original route plan crossed the Sandhills, the large wetland ecosystem in Nebraska, and the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the largest reserves of fresh water in the world.[50][58] The Ogallala Aquifer spans eight states, provides drinking water for two million people, and supports $20 billion in agriculture.[59] Critics say that a major leak could ruin drinking water and devastate the mid-western U.S. economy.[51][60] After opposition for laying the pipeline in this area, TransCanada agreed to change the route and skip the Sand Hills.[49]

Research hydrogeologist James Goeke, professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska, who has spent more than 40 years studying the Ogallala Aquifer, phoned TransCanada officials and quizzed them on the project, and satisfied himself that danger to the aquifer was small, because he believes that a spill would be unlikely to penetrate down into the aquifer, and if it did, he believes that the contamination would be localized. He noted: "A lot of people in the debate about the pipeline talk about how leakage would foul the water and ruin the entire water supply in the state of Nebraska and that's just a false,"[61] Goeke said "... a leak from the XL pipeline would pose a minimal risk to the aquifer as a whole."[62]

Pipeline industry spokesmen have noted that thousands of miles of existing pipelines carrying crude oil and refined liquid hydrocarbons have crossed over the Ogallala Aquifer for years, in southeast Wyoming, eastern Colorado and New Mexico, western Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.[63][64][65][66][67] The Pioneer crude oil pipeline crosses east-west across Nebraska, and the Pony Express pipeline, which crosses the Ogallala Aquifer in Colorado, Nebraska, and Kansas, was being converted as of 2013 from natural gas to crude oil, under a permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.[68]

Portions of the pipeline will also cross an active seismic zone that had a 4.3 magnitude earthquake as recently as 2002.[59] Opponents claim that TransCanada applied to the U.S. government to use thinner steel and pump at higher pressures than normal.[60] In October 2011, The New York Times questioned the impartiality of the environmental analysis of the pipeline done by Cardno Entrix, an environmental contractor based in Houston. The study found that the pipeline would have limited adverse environmental impacts, but was authored by a firm that had "previously worked on projects with TransCanada and describes the pipeline company as a 'major client' in its marketing materials".[69]

According to The New York Times, legal experts questioned whether the U.S. government was "flouting the intent" of the Federal National Environmental Policy Act, which "[was] meant to ensure an impartial environmental analysis of major projects".[69] The report prompted 14 senators and congressmen to ask the State Department inspector general on October 26, 2011 "to investigate whether conflicts of interest tainted the process" for reviewing environmental impact.[70] In August 2014, a study was published that concluded the pipeline could produce up to 4 times more global warming pollution than the State Department's study indicated. The report blamed the discrepancy on a failure to take calculate the increase in consumption due to the drop in the price of oil that would be spurred by the pipeline.[71]

TransCanada CEO Russ Girling has described the Keystone Pipeline as "routine", noting that TransCanada has been building similar pipelines in North America for half a century and that there are 200,000 miles (320,000 km) of similar oil pipelines in the United States today. He also stated that the Keystone Pipeline will include 57 improvements above standard requirements demanded by U.S. regulators so far, making it "the safest pipeline ever built".[72] Rep. Ed Whitfield, a member of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce concurred, saying "this is the most technologically advanced and safest pipeline ever proposed."[73] However, while TransCanada had asserted that a set of 57 conditions will ensure Keystone XL's safe operation, Anthony Swift of the Natural Resources Defense Council asserted that all but a few of these conditions simply restate current minimum standards.[74]

Environmental organizations such as the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) also oppose the project due to its transportation of oil from oil sands.[55] In its March 2010 report, the NRDC stated that "the Keystone XL Pipeline undermines the U.S. commitment to a clean energy economy," instead "delivering dirty fuel at high costs".[75] On June 23, 2010, 50 Democrats in Congress in their letter to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned that "building this pipeline has the potential to undermine America's clean energy future and international leadership on climate change," referencing the higher input quantity of fossil fuels necessary to take the tar and turn it into a usable fuel product in comparison to other conventionally derived fossil fuels.[76][77]

NASA climate scientist James Hansen stated in 2013 that "moving to tar sands, one of the dirtiest, most carbon-intensive fuels on the planet" is a step in exactly the wrong direction, "indicating either that governments don't understand the situation or that they just don't give a damn".[77] House Energy and Commerce Committee chairman Henry Waxman has also urged the State Department to block Keystone XL for greenhouse gas emission reasons.[78][79]

In December 2010, No Tar Sands Oil campaign, sponsored by action groups including Corporate Ethics International, NRDC, Sierra Club, 350.org, National Wildlife Federation, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, and Rainforest Action Network, was launched.[80]

These arguments were questioned by the National Post columnist Diane Francis who argues that opposition to the pipeline "makes no sense because emissions from the oil sands are a fraction of the emissions from coal and equivalent to California heavy crude oils or ethanol" and questioned why "none of these has been getting the same attention as the oil sands and this pipeline."[81]

In a speech to the Canadian Club in Toronto on September 23, 2011, Joe Oliver, Canada's Minister of Natural Resources, sharply criticized opponents of oil sands development and the pipeline, arguing that:[82]

- The total area that has been affected by surface mining represents only 0.1% of Canada's boreal forest.

- The oil sands account for about 0.1% of global greenhouse-gas emissions.

- Electricity plants powered by coal in the U.S. generate almost 40 times more greenhouse-gas emissions than Canada's oil sands (the coal-fired electricity plants in the State of Wisconsin alone produce the equivalent of the entire GHG emissions of the oil sands).

- California bitumen is more GHG-intensive than the oil sands.

Conflicts of interest[edit]

On May 4, 2012, the U.S. Department of State selected Environmental Resources Management (ERM) to author a Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, after the Environmental Protection Agency had found previous versions of the study, by contractor Cardno Entrix,[83] to be extremely inadequate.[84] Project opponents panned the study on its release, calling it a "deeply flawed analysis".[85] An investigation by Mother Jones magazine revealed that the State Department had redacted the biographies of the study's authors to hide their previous contract work for TransCanada and other oil companies with an economic interest in the project.[86] Based on an analysis of public documents on the State Department website, one critic asserted that "Environmental Resources Management was paid an undisclosed amount under contract to TransCanada to write the statement".[87]

Political issues[edit]

The pipeline is a top-tier election issue for the November 4, 2014 United States elections for the United States Senate, for U.S. House of Representatives, for governors in states and territories, and for many state and local positions as well. One election-year dilemma facing the Democrats, is whether or not Obama should approve the completion of the Keystone XL pipeline.[88] Tom Steyer, and other wealthy environmentalists, are committed to "make climate change a top-tier issue" in the elections with opposition to Keystone XL as "a significant part of that effort."[88]

In February 2011, environmental journalist David Sassoon of Inside Climate News reported that Koch Industries were poised to be "big winners" from the pipeline.[89] In May 2011, Congressmen Waxman and Rush wrote a letter to the Energy and Commerce Committee citing the Reuters story, and urging the Committee to request documents from Koch Industries relating to the Keystone XL pipeline.[90][91]

Landowners in the path of the pipeline have complained about threats by TransCanada to confiscate private land and lawsuits to allow the "pipeline on their property even though the controversial project has yet to receive federal approval."[92] As of October 17, 2011, TransCanada had "34 eminent domain actions against landowners in Texas" and "22 in South Dakota." Some of those landowners gave testimony for a House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing in May 2011.[92] In his book The Pipeline and the Paradigm, Samuel Avery quotes landowner David Daniel in Texas, who claims that TransCanada illegally seized his land via eminent domain by claiming to be a public utility rather than a private firm.[93]

In January 2012, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Tenn.) requested a new report on the environmental review process.[94]

Commentator Bill Mann has linked the Keystone postponement to the Michigan Senate's rejection of Canadian funding for the proposed Detroit River International Crossing and to other recent instances of "U.S. government actions (and inactions) that show little concern about Canadian concerns." Mann drew attention to a Maclean's article sub-titled "we used to be friends"[95] about U.S./Canada relations after President Obama had "insulted Canada (yet again)" over the pipeline.[96]

Canadian Ambassador Doer observes that Obama's "choice is to have it come down by a pipeline that he approves, or without his approval, it comes down on trains."[97]

During the 2014 Pacific Northwest Economic Region Summit in Whistler, B.C., Canada’s US Ambassador Gary Doer stated that there is no proof, be it environmental, economic, safety or scientific, that construction work on Keystone XL should not go ahead. Doer said that all the evidence supports a favourable decision by the US government for the controversial pipeline. [98]

Geopolitical issues[edit]

Proponents for the Keystone XL pipeline argue that it would allow the U.S. to increase its energy security and reduce its dependence on foreign oil.[99][100] TransCanada CEO Russ Girling has argued that "the U.S. needs 10 million barrels a day of imported oil" and the debate over the proposed pipeline "is not a debate of oil versus alternative energy. This is a debate about whether you want to get your oil from Canada or Venezuela or Nigeria."[101] However, an independent study conducted by the Cornell ILR Global Labor Institute refers to some studies (e.g. a 2011 study by Danielle Droitsch of Pembina Institute) according to which "a good portion of the oil that will gush down the KXL will probably end up being finally consumed beyond the territorial United States". It also states that the project will increase the heavy crude oil price in the Midwestern United States by diverting oil sands oil from the Midwest refineries to the Gulf Coast and export markets.[23]

TransCanada's Girling has also argued that if Canadian oil doesn't reach the Gulf through an environmentally friendly buried pipeline, that the alternative is oil that will be brought in by tanker, a mode of transportation that produces higher greenhouse-gas emissions and that puts the environment at greater risk.[72] Diane Francis has argued that much of the opposition to the oil sands actually comes from foreign countries such as Nigeria, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia, all of whom supply oil to the United States and who could be affected if the price of oil drops due to the new availability of oil from the pipeline. She cited as an example an effort by Saudi Arabia to stop pro-oil-sands television commercials.[81] TransCanada had said that development of oil sands will expand regardless of whether the crude oil is exported to the United States or alternatively to Asian markets through Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines or Kinder Morgan's Trans-Mountain line.[102]

Indigenous issues[edit]

Many Native Americans and Indigenous Canadians are opposed to the Keystone XL project for various reasons,[103] including possible damage to sacred sites, pollution, and water contamination, which could lead to health risks among their communities.[104]

On September 19, 2011, a number of leaders from Native American bands in the United States and First Nations bands from Canada were arrested for protesting the Keystone XL outside the White House. According to Debra White Plume, a Lakota activist, indigenous peoples "... have thousands of ancient and historical cultural resources that would be destroyed across [their] treaty lands".[104] TransCanada's Pipeline Permit Application to the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission states project impacts that include potential physical disturbance, demolition or removal of "prehistoric or historic archaeological sites, districts, buildings, structures, objects, and locations with traditional cultural value to Native Americans and other groups".[105]

Indigenous communities are also concerned with health risks posed by the extension of the Keystone pipeline.[106] Locally caught fish and untreated surface water would be at risk for contamination through oil sands extraction, and are central to the diets of many indigenous peoples.[107] Earl Hatley, an environmental activist who has worked with Native American tribes[108] has expressed concern about the environmental and public health impact on Native Americans.

TransCanada has developed an Aboriginal Relations policy in order to confront some of these conflicts. In 2004, TransCanada Pipelines Ltd. made a major donation to the University of Toronto "to promote education and research in the health of the Aboriginal population".[109] Another proposed solution is TransCanada's Aboriginal Human Resource Strategy, which was developed to facilitate aboriginal employment and to provide "opportunities for Aboriginal businesses to participate in both the construction of new facilities and the ongoing maintenance of existing facilities"[110]

Economic issues[edit]

Russ Girling, president and CEO of TransCanada, touted the positive impact of the project by "putting 20,000 US workers to work and spending $7 billion stimulating the US economy".[111] These numbers come from a 2010 report written by The Perryman Group, a financial analysis firm based in Texas that was hired by TransCanada to evaluate Keystone XL.[112][113] The numbers in the Perryman Group report have been disputed by an independent study conducted by the Cornell ILR Global Labor Institute, which found that while the Keystone XL would result in 2,500 to 4,650 temporary construction jobs, this impact will be reduced by higher oil prices in the Midwest, which will likely reduce national employment.[23] However, it will increase gasoline availability to the Northeast and expand the Gulf refining industry. The State Department estimates that the pipeline would create about 5,000 to 6,000 temporary jobs in the United States during the two-year construction period.[114][115]

On January 27, 2012, Greenpeace Executive Director Phil Radford appealed to the Securities and Exchange Commission to review TransCanada's claims that the Keystone Pipeline would create 20,000 jobs. Stating that the company had "consistently used public statements and information it knows are false in a concerted effort to secure permitting approval" of the pipeline, Radford argued that TransCanada had "misled investors, U.S. and Canadian officials, the media, and the public at large in order to bolster its balance sheets and share price".[116]

On July 27, 2013, President Obama stated "The most realistic estimates are this might create maybe 2,000 jobs during the construction of the pipeline, which might take a year or two, and then after that we're talking about somewhere between 50 and 100 jobs in an economy of 150 million working people." The estimate of 2,000 during construction came under heavy attack, while the long-term, permanent job estimates did not receive as much criticism.[117] The Associated Press noted that it was unclear where the president's figure of 2,000 jobs came from. The U.S. State Department's Preliminary Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, issued in March 2013, estimated 3,900 direct jobs and 42,000 direct and indirect jobs during construction.[118]

There might be unintended economic consequences to the construction of Keystone XL. As an example, the additional north-south crude oil transport capacity brought by Keystone XL will increase the price the oil sands producers receive for their oil. These higher revenues will have a positive impact on the development of the industry in Alberta. In return, due to the Petrodollar nature of the Canadian currency these same additional revenues will strengthen the Canadian dollar versus the United States dollar. Based on historical trends, this stronger Canadian dollar will result in a reduction of the competitiveness of Canada's manufacturing industry and could lead to the loss of 50,000 to 100,000 jobs in Canada's manufacturing sector.[119][unreliable source?] Many of these jobs, such as the ones in the auto industry, would likely find their way south and have a positive impact on manufacturing employment in the U.S.[120][not in citation given]

Glen Perry, a petroleum engineer for Adira Energy, has warned that including the Alberta Clipper pipeline owned by TransCanada's competitor Enbridge, there is an extensive overcapacity of oil pipelines from Canada.[121] After completion of the Keystone XL line, oil pipelines to the U.S. may run nearly half-empty. The expected lack of volume combined with extensive construction cost overruns has prompted several petroleum refining companies to sue TransCanada. Suncor Energy hoped to recoup significant construction-related tolls, though the U.S. Energy Regulatory Commission did not rule in their favor. According to The Globe and Mail,

The refiners argue that construction overruns have raised the cost of shipping on the Canadian portion of Keystone by 145 per cent while the U.S. portion has run 92 per cent over budget. They accuse TransCanada of misleading them when they signed shipping contracts in the summer of 2007. TransCanada nearly doubled its construction estimates in October 2007, from $2.8-billion (U.S.) to $5.2-billion.[122]

Due to an exemption the state of Kansas gave TransCanada, the local authorities would lose $50 million public revenue from property taxes for a decade.[28]

In the United States, Democrats are concerned that Keystone XL would not provide petroleum products for domestic use, but simply facilitate getting Alberta oil sands products to American coastal ports on the Gulf of Mexico for export to China and other countries.[43]

Frustrated by delays in getting approval for Keystone XL (via the Gulf of Mexico), the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines (via Kitimat, BC) and the expansion of the existing TransMountain line to Vancouver, Alberta has intensified exploration of two northern projects "to help the province get its oil to tidewater, making it available for export to overseas markets".[123] Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, spent $9 million by May 2012 and $16.5 million by May 2013 to promote Keystone XL.[43] Until Canadian crude oil accesses international prices like LLS or Maya crude oil by "getting to tidewater" (south to the U.S. Gulf ports via Keystone XL for example, west to the BC Pacific coast via the proposed Northern Gateway line to ports at Kitimat, BC or north via the northern hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk, near the Beaufort Sea),[123] the Alberta government (and to some extent, the Canadian government) is losing from $4 – 30 billion in tax and royalty revenues as the primary product of the oil sands, Western Canadian Select(WCS), the bitumen crude oil basket, is discounted so heavily against West Texas Intermediate (WTI) while Maya crude oil, a similar product close to tidewater, is reaching peak prices.[124] Calgary-based Canada West Foundation warned in April 2013, that Alberta is "running up against a [pipeline capacity] wall around 2016, when we will have barrels of oil we can't move".[123]

Pipeline opponents warn of disruption of farms and ranches during construction,[125] and point to damage to water mains and sewage lines sustained during construction of an Enbridge crude oil pipeline in Michigan.[126] A report by the Cornell University Global Labor Institute noted of the 2010 Enbridge Tar Oil Spill along the Kalamazoo River in Michigan: "The experience of Kalamazoo residents and businesses provides an insight into some of the ways a community can be affected by a tar sands pipeline spill. Pipeline spills are not just an environmental concern. Pipeline spills can also result in significant economic and employment costs, although the systematic tracking of the social, health, and economic impacts of pipeline spills is not required by law. Leaks and spills from Keystone XL and other tar sands and conventional crude pipelines could put existing jobs at risk.."[125]

Safety issue[edit]

A USA Today editorial pointed out that the 2013 Lac-Mégantic derailment in Quebec, in which crude oil carried by rail cars exploded and killed 50 people, highlights the safety of pipelines compared to truck or rail transport. The oil in the Lac-Mégantic rail cars came from the Bakken Formation in North Dakota, an area that would be served by the Keystone expansion.[127] Increased oil production in North Dakota has exceeded pipeline capacity since 2010, leading to increasing volumes of crude oil being shipped by truck or rail to refineries.[128] Canadian journalist Diana Furchtgott-Roth commented: "If this oil shipment had been carried through pipelines, instead of rail, families in Lac-Mégantic would not be grieving for lost loved ones today, and oil would not be polluting Lac Mégantic and the Chaudière River."[129] A Wall Street Journal article in March of 2014 points out that the main reason oil producers from the North Dakota Bakken Shale region are using rail and trucks to transport oil is economics not pipeline capacity. The Bakken oil is of a higher quality than the Canadian Sand oil and can be sold to east coast refinery at a premium that they would not get sending it to Gulf refineries. [130] The article goes on to state that there is little support remaining among these producers for the Keystone XL.

Public Opinion[edit]

Public opinion polls taken by independent national polling organizations have shown majority support for the proposed pipeline in the U.S. A September 2013 poll by the Pew Center found 65% favored the project, versus 30% opposed. The same poll found the pipeline favored by majorities of men (69%), women (61%), Democrats (51%), Republicans (82%), independents (64%), as well as by those in every division of age, education, economic status, and geographic region. The only group identified by the Pew poll with less than majority support for the pipeline was among those Democrats who identified themselves as liberal (41% in favor versus 54% opposed).[131]

The overall results of polls on the Keystone XL pipeline taken by independent national polling organizations are as follows:

- Gallup (March 2012): 57% government should approve, 29% government should not approve[132]

- Rasmussen (January 2014): 57% favor, 28% oppose (of likely voters)[133]

- Pew Center (September 2013): 65% favor, 30% oppose[131]

Ongoing developments[edit]

Protests and postponements[edit]

In 2011, environmental and global warming activist Bill McKibben took the question of the pipeline to NASA scientist James Hansen, who told McKibben the pipeline would be "game over for the planet".[134] McKibben and other activists organized opposition, which coalesced in August 2011 with over 1000 nonviolent arrests at the White House, which included environmental leaders such as Phil Radford and celebrities like Daryl Hannah.[135] They promised to continue to challenge President Obama to stand by his 2008 call to "be the generation that finally frees America from the tyranny of oil"[136] as he entered the 2012 reelection campaign. A relatively broad coalition came together, including the Republican governor Dave Heineman and senators Ben Nelson (D) and Mike Johanns (R) from Nebraska, and some Democratic funders like Susie Tompkins Buell.[136]

On November 6, 2011, several thousand environmentalist supporters, some shouldering a long black inflatable replica of a pipeline, formed a human chain around the White House to convince Barack Obama to block the controversial Keystone XL project. Organizer Bill McKibben said, "this has become not only the biggest environmental flash point in many, many years, but maybe the issue in recent times in the Obama administration when he's been most directly confronted by people in the street. In this case, people willing, hopeful, almost dying for him to be the Barack Obama of 2008."[137]

On October 4, 2012, actress and activist Daryl Hannah and 78-year-old Texas landowner Eleanor Fairchild were arrested for criminal trespassing and other charges after they were accused of standing in front of pipeline construction equipment on Fairchild's farm in Winnsboro, a town about 100 miles (160 km) east of Dallas.[138] Fairchild has owned the land since 1983 and refused to sign any agreements with TransCanada. Her land was seized by eminent domain.

On October 31, 2012, Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein was also arrested in Texas for criminal trespass after trying to deliver food and supplies to the Keystone XL protesters.[139][140]

On February 17, 2013, approximately 35,000 to 50,000 protestors attended a rally in Washington, D.C. organized by The Sierra Club, 350.org, and The Hip Hop Caucus, in what Bill McKibben described as "the biggest climate rally by far, by far, by far, in U.S. history".[141][142] The event featured Lennox Yearwood; Chief Jacqueline Thomas, immediate past chief of the Saik'uz First Nation; Van Jones; Crystal Lameman, of Beaver Lake Cree Nation; Michael Brune, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), and others as invited speakers.[143] Simultaneous 'solidarity' protests were also organized in several other cities across the United States, Europe, and Canada.[citation needed] Protesters called on President Obama to reject the planned pipeline extension when deciding the fate of the pipeline after Secretary of State John Kerry completes a review of the project.[144]

"[B]ecause of broader market dynamics and options for crude oil transport in the North American logistics system, the upstream and downstream activities are unlikely to be substantially different whether or not the proposed Project is constructed."[145]

On March 2, 2014, approximately 1000-1200 protesters marched from Georgetown University to the White House to stage a protest against the Keystone Pipeline. 398 arrests were made of people tying themselves to the White House fence with zip-ties and laying on a black tarp in front of the fence. The tarp represented an oil spill, and many protesters dressed in white jumpsuits covered in black ink, symbolizing oil-covered HazMat suits, laid down upon the tarp. This was a gathering of mostly college students, and has been called the largest gathering of students in protest in a generation.[according to whom?]

Alternative projects[edit]

On November 16, 2011, Enbridge announced it was buying ConocoPhillips' 50% interest in the Seaway pipeline that flowed from the Gulf of Mexico to the Cushing hub. In cooperation with Enterprise Products Partners LP it is reversing the Seaway pipeline so that an oversupply of oil at Cushing can reach the Gulf.[146] This project replaced the earlier proposed alternative Wrangler pipeline project from Cushing to the Gulf Coast.[147] It began reversed operations on May 17, 2012.[148] However, according to industries, the Seaway line alone is not enough for oil transportation to the Gulf Coast.[149]

On January 19, 2012, TransCanada announced it may shorten the initial path to remove the need for federal approval.[150] TransCanada said that work on that section of the pipeline could start in June 2012[151] and be on-line by the middle to late 2013.[152]

In April 2013, it was learned that the government of Alberta was investigating, as an alternative to the pipeline south through the United States, a shorter all-Canadian pipeline north to the Arctic coast, from where the oil would be taken by tanker ships through the Arctic Ocean to markets in Asia and Europe[153] and in August, TransCanada announced a new proposal to create a longer all-Canada pipeline, called Energy East, that would extend as far east as the port city of Saint John, New Brunswick, at the same time providing feedstock to refineries in Montreal, Quebec City and Saint John.[154]

The Enbridge "Alberta Clipper" (Line 67) expansion has been continuing during late 2013 with little political notice although it adds approximately the same cross-border transport capacity as the Keystone XL project.[155]

Lawsuits[edit]

In September 2009, independent refiner CVR sued TransCanada for Keystone Pipeline tolls seeking $250 million damage compensation or release from transportation agreements. CVR alleged that the final tolls for the Canadian segment of the pipeline were 146% higher than initially presented, while the tolls for the U.S. segment were 92% higher.[156] In April 2010, three smaller refineries sued TransCanada to break Keystone transportation contracts, saying the new pipeline has been beset with cost overruns.[122]

In October 2009, a suit was filed by the Natural Resources Defense Council that challenged the pipeline on the grounds that its permit was based on a deficient environmental impact statement. The suit was thrown out by a federal judge on procedural grounds, ruling that the NRDC lacked the authority to bring it.[157]

In June 2012, Sierra Club, Inc., Clean Energy Future Oklahoma, and the East Texas Sub Regional Planning Commission filed a joint complaint in the United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma seeking injunctive relief and petitioning for a review of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' action in issuing Nationwide Permit 12 permits for the Cushing, Oklahoma, to the Gulf Coast portion of the pipeline. The suit alleges that, contrary to the federal Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 701 et. seq., the Corps' issuance of the permits was arbitrary and capricious and an abuse of discretion.[158]

See also[edit]

- Pony Express Pipeline

- Double H Pipeline

- Coal export terminals

- List of articles about Canadian tar sands

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Gulf Coast area "refers to the region from Houston, Texas, to Lake Charles, Louisiana" (USSD SEIS March 1, 2013 p. ES-1).

- ^ It was presented to the United States State Department as a independent economic utility in February 2012, sidestepping the requirement for a Presidential Permit because it does not cross an international border (United States Department of State SEIS March 1, 2013 p. ES1).

- ^ The Alberta government placed a $30, 000 ad entitled "Keystone XL: The Choice of Reason" in The New York Times to counter the editorial (CBC March 17, 2013).

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Keystone Pipeline System". TransCanada. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ a b c d United States Department of State Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (2013-03-01) (PDF). Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement for the KEYSTONE XL PROJECT Applicant for Presidential Permit: TransCanada Keystone Pipeline, LP (SEIS) (Report). United States Department of State. http://keystonepipeline-xl.state.gov/documents/organization/205719.pdf. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- ^ a b "Keystone Pipeline". Calgary, Alberta, Canada: TransCanada Corporation. 2013-01. Retrieved 2013-03-17. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ a b c , completing the pipeline path from Hardisty, Alberta to Nederland, Texas. "US leg of controversial Canadian oil pipeline opens". Space Daily. 2014-01-22. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ^ a b ":Keystone XL Pipeline: About the project". TransCanada.

- ^ "TransCanada Wins as Obama Keystone Permit Seen". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ^ Bergin, Nicholas (2014-04-18), Nebraska lawsuit delays decision on Keystone XL, Lincoln Journal Star Online, retrieved 2014-08-14

- ^ "Gulf Coast Pipeline Project". TransCanada Corporation. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Broder, John M.; Krauss, Clifford (28 February 2012). "Keystone XL Pipeline". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c "Keystone Pipeline". A Barrel Full. 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ a b c Hovey, Art (2008-06-12). "TransCanada Proposes Second Oil Pipeline". Lincoln Journal-Star (Downstream Today). Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ a b c "TransCanada, ConocoPhillips To Expand Keystone To Gulf Coast". TransCanada (Downstream Today). 2008-07-16. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ a b "Keystone Pipeline System". TransCanada Corporation. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "Valero: Prospective Keystone Shipper". Valero Energy (Downstream Today). 2008-07-16. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ transcanada.com (February 9, 2005). "TransCanada Proposes Keystone Oil Pipeline Project". TransCanada Corporation.

- ^ "Union calls on Ottawa to block Keystone". Upstream Online (NHST Media Group). 2007-10-24. (subscription required). Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ "TransCanada: Keystone Construction to Start Early Next Year". TransCanada Corporation (Downstream Today). 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "State Dept. Grants Keystone Permit; Work To Start In Q2". TransCanada Corporation (Downstream Today). 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "ConocoPhillips Acquires 50% Stake in Keystone". ConocoPhillips (Downstream Today). 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ O'Connor, Phillip (2010-06-08). "TransCanada's Keystone pipeline ready for flow, but is the market there?". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ^ a b Newton, Ken (2010-06-09). "Oil Flows Through Keystone". St. Joseph News-Press (Downstream Today). Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ "NEB Sets Keystone XL Hearing". National Energy Board (Downstream Today). 2009-05-13. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ a b c d (PDF) Pipe dreams? Jobs Gained, Jobs Lost by the Construction of Keystone XL (Report). ILR School Global Labor Institute. September 2011. http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/globallaborinstitute/research/upload/GLI_KeystoneXL_Reportpdf.pdf. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ a b "NEB Okays Keystone XL". National Energy Board (Downstream Today). 2010-03-11. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ "Keystone XL Clears Hurdle In South Dakota". South Dakota Public Utilities Commission (Downstream Today). 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ a b Sudekum Fisher, Maria (2010-07-21). "EPA: Keystone XL impact statement needs revising". Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Welsch, Edward (2010-07-21). "EPA Calls for Further Study of Keystone XL". Downstream Today. Dow Jones Newswires. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ a b Goldstein, David (2011-02-13). "Oil pipeline from Canada stirring anger in U.S. Great Plains". McClatchy Newspapers. McClatchy Washington Bureau. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ Tracy, Tennille; Welsch, Edward (2011-08-26). "Keystone Poses 'No Significant Impacts' to Most Resources Along Path – US". Downstream Today. Dow Jones Newswires. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ^ a b c Kemp, John (2012-09-06). "Keystone modifications call Obama's bluff". Reuters. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ "TransCanada to Work with Department of State on New Keystone XL Route Options" (Press release). TransCanada. 2011-11-10. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ "Media Advisory – State of Nebraska to Play Major Role in Defining New Keystone XL Route Away From the Sandhills" (Press release). TransCanada. 2011-11-14. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ Avok, Michael (2011-11-22). "Nebraska governor signs bills to reroute Keystone pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ Daly, Matthew (2011-11-30). "GOP bill would force action on Canada oil pipeline". Deseret News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (January 18, 2012). "Obama denies Keystone XL pipeline permit". CBS News. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (January 18, 2012). "Keystone XL pipeline: Obama rejects controversial project". The Guardian (London). Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "TransCanada proposes new Keystone XL route in Nebraska". Reuters. 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- ^ Bachand, Thomas. "Final Response to FOIA: "No GIS Data"". Keystone Mapping Project. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Editorial (March 10, 2013). "When to Say No". The New York Times.

- ^ Cynthia Giles (April 22, 2013), Letter from C. Giles (EPA) to J. Fernandez & K.-A. Jones (SD) (PDF), United States Environmental Protection Agency, pp. 1–7, retrieved September 14, 2013

- ^ "Oil, money and politics; EPA snags Keystone XL pipeline". CNN. April 23, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Cynthia Jones (U.S. EPA), letter to U.S. Dept. of State concerning Keystone XL pipeline, 22 Apr, 2013.

- ^ a b c Goodman, Lee-Anne (22 May 22, 2013). "Republicans aim to take Keystone XL decision out of Obama's hands". The Canadian Press. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ "Remarks of the President" (Press release). The White House. 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ^ "Canada-US link gets green light". Upstream Online (NHST Media Group). 2008-03-14. (subscription required). Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ a b "TransCanada: Keystone Construction to Begin in Spring". TransCanada Corporation (Downstream Today). 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ "TransCanada begins Keystone pipeline in Texas". Fox News. 2014-01-22.

- ^ "TransCanada's quarterly profit rises to $390 million". Canada.com (CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc.). 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ a b VanderKlippe, Nathan (2011-12-24). "The politics of pipe: Keystone's troubled route". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- ^ a b Media Notes on Keystone XL Pipeline Project Review Process: Decision to Seek Additional Information (Report). U.S.State Department. November 10, 2011. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2011/11/176964.htm. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ a b (PDF) Level IV Ecoregions of Kansas and Nebraska (Report). 2001. http://www.kdheks.gov/befs/download/bibliography/ksne_ecoregions.pdf.

- ^ "Tar Sands and Safety Risk". Natural Resource Defense Council. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "XL Pipeline". Sierra Club Nebraska. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Gov. Heineman: Pipeline Re-Routing is Nebraska Common Sense" (Press release). Office of Governor of Nebraska. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Editorial: Tar Sands and the Carbon Numbers". The New York Times. 2011-08-21. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- ^ "Draft Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS)". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Avery, Samuel (2013). The Pipeline and the Paradigm. Ruka Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-9855748-2-6.

- ^ "World's Largest Aquifer Going Dry". U.S. Water News Online. February 2006. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ a b Anderson, Mitchell (2010-07-07). "Ed Stelmach's Clumsy American Romance". The Tyee. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ a b Dembicki, Geoff (2010-06-21). "Gulf Disaster Raises Alarms about Alberta to Texas Pipeline". The Tyee. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Shelby Fleig and Kyle Cummings, UNL expert: Ogallala Aquifer has little risk of Keystone pipeline oil spills, Daily Nebraskan (Lincoln), 15 Apr. 2013.

- ^ James Goeke (4 October 2011). "The Truth About Aquifers". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Larry Lakely, Map of Pipelines and the Ogallala Aquifer, 2012, 20 Jan. 2012.

- ^ Andrew Black and David Holt, Guest View: We need crude oil pipelines Lincoln Journal Star, 12 July 2011.

- ^ Allegro Energy Group, How Pipelines Make the Oil Market Work – Their Networks, Operation and Regulation, December 2001, Association of Oil Pipe Lines and American Petroleum Institute, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Pipeline 101, Refined products pipelines, accessed 8 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Oil Sands fact Check, Myth vs. Fact: KXL will Threaten the Ogallala Aquifer 20 May 2012.

- ^ Paul Hammel, Smaller oil pipeline to cross Ogallala Aquifer, Omaha.com, 23 Aug. 2012.

- ^ a b News (2011-10-07). "Pipeline Review Is Faced With Question of Conflict". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Tar Sands Pipeline Probe Urged Sen. Bernie Sanders October 26, 2011

- ^ Associated Press. "Study: Keystone pollution higher". www.politico.com. Politico. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b Cattaneo, Claudia (September 9, 2011). "TransCanada in eye of the storm". Financial Post.

- ^ "Keystone XL the 'safest pipeline ever'", Sun News Network, 2 December 2011.

- ^ McGowan, Elizabeth (2011-09-19). "Keystone XL Pipeline Safety Standards Not as Rigorous as They Seem". InsideClimate News. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ^ "Say No to Tar Sands Pipeline" (PDF). NRDC. 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ Casey-Lefkowitz, Susan (2010-06-23). "House members say tar sands pipeline will undermine clean energy future". NRDC. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Bartholomew (2010-06-24). "Enviro Groups, 50 Congressmen Mobilize Against Keystone XL". The Commercial Appeal (Downstream Today). Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Rascoe, Ayesha; Haggett, Scott (2010-07-06). "Key US lawmaker opposes Canadian oil sands pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ^ Dvorak, Phred; Welsch, Edward (2010-07-08). "Oil Sands Push Tests US-Canada Ties". The Wall Street Journal (Downstream Today). Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ O'Meara, Dina (2010-12-08). "Pressure in U.S. mounts against oilsands pipeline". The Calgary Herald. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- ^ a b Francis, Diane (2011-09-23). "Foreign interests attack oil sands". Financial Post. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ "NOTA Bene". National Post. 24 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ http://www.keystonepipeline-xl.state.gov/

- ^ "Keystone XL: State Department cleared of conflict, not ineptness". Los Angeles Times. 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Harris, Paul (2013-03-02). "Keystone XL pipeline report slammed by activists and scientists". The Guardian (London). ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- ^ Kroll, Andy (21 March 2013). "EXCLUSIVE: State Dept. Hid Contractor's Ties to Keystone XL Pipeline Company". Mother Jones (San Francisco: Mother Jones and the Foundation for National Progress). Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ^ Johnson, Brad (2013). "'State Department' Keystone XL Report Actually Written By TransCanada Contractor". grist.org. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ a b Senate Democrats Urge Obama To Approve Keystone XL, Washington, DC: Huffington Post, 2014-04-10, retrieved 2014-04-22

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ^ Sassoon, David (2011-02-10). "Koch Brothers Positioned To Be Big Winners If Keystone XL Pipeline Is Approved". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ^ Waxman, Henry A.; Rush, Bobby L. (2011-05-20). "Reps. Waxman and Rush Urge Committee to Request Documents from Koch Industries Regarding Keystone XL Pipeline". Committee on Energy and Commerce Democrats. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ^ Sheppard, Kate (2011-05-23). "Waxman Targets the Koch Brothers". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Leslie; Frosch, Dan (2011-10-17). "Eminent Domain Fight Has a Canadian Twist". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ^ Avery, Samuel (2103). The Pipeline and the Paradigm. Ruka Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-9855748-2-6. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ http://search.proquest.com.kckcc.idm.oclc.org/docview/920768194?accountid=11802

- ^ Mann, Bill, "Americans should be thankful for Canada", MarketWatch, November 24, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ Savage, Luiza Ch., "The U.S. and Canada: we used to be friends", Maclean's, November 21, 2011 8:00 am. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ "'Trains or pipelines,' Doer warns U.S. over Keystone". The Globe & Mail (Toronto). 2013-07-28.

- ^ "Canada’s US ambassador pushes for Keystone XL decision". energyglobal.com. July 24, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Energy and Commerce: The Keystone XL Pipeline". U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Say Yes To Building The Keystone Oil Pipeline". USA Today. 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ^ Hussein, Yadullah (2011-09-23). "Keystone 'exaggerated rhetoric' untrue". Financial Post.

- ^ Welsch, Edward (2010-06-30). "TransCanada: Oil Sands Exports Will Go To Asia If Blocked In US". Downstream Today. Dow Jones Newswires. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ "Keystone XL Pipeline and Indigenous Peoples". Indigenous Peoples Issues and Resources. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b "First Nations and American Indian Leaders Arrested In Front Of White House To Protest Keystone XL Pipeline". Bioterrorism Week. (Sept. 19, 2011): p11. Academic OneFile. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Application to the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission for a Permit for the Keystone XL Pipeline Under the Energy Conversion and Transmission Facility Act". puc.sd.gov. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Swift, Anthony; Casey-Lefkowitz, Susan; Shope, Elizabeth (February 2011). "Tar Sands Pipeline Safety Risks" (PDF). National Resources Defense Council. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Timoney, Kevin P. "A Study of Water and Sediment Quality as Related to Public Health Issues". Treeline Ecological Research. www.tothetarsands.ca. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Earl Hatley: Portrait of an Oklahoma activist". The Current. www.currentland.com. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "New Appointments in Aboriginal Health at the University of Toronto". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. eISSN 2242-3982 (print volumes from 1972–2011: ISSN 1239-9736) (Circumpolar Health Supplements): 294. 2004. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Community, Aboriginal and Native American Relations". TransCanada.com. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ^ TransCanada CEO on Proposed Pipeline. Fox News Channel. 2011-08-31. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ The Impact of Developing the Keystone XL Pipeline Project on Business Activity in the US: An Analysis Including State-by-State Construction Effects and an Assessment of the Potential Benefits of a More Stable Source of Domestic Supply (Report). Perryman Group. June 2010. http://www.perrymangroup.com/reports/TransCanada.pdf. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ Brainard, Curtis (2012-01-12). "Keystone XL Jobs Bewilder Media. Reporters still fumbling numbers in wake of pipeline's rejection". The Observatory (Columbia Journalism Review). Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ Sherter, Alain (2012-01-19). "Keystone pipeline: How many jobs really at stake?". CBS News. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ Hargreaves, Steve (2011-12-14). "Keystone pipeline: How many jobs it would really create". CNN. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- ^ Radford, Phil (2014-01). "Greenpeace Letter to Securities and Exchange Commission". Retrieved 2014-03-04 citation needed. Check date values in:

|date=, |accessdate=(help) - ^ "Obama Questions Keystone XL Pipeline Job Projections". Huffington Post. 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ^ Associated Press, AP: Obama Understates Keystone XL Pipeline Jobs By Thousands, 1 Aug. 2013

- ^ "On the economic impact of the Keystone pipeline". Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ Cato, Jeremy (September 10, 2012). "Canadian Auto Workers union: singing off-key as jobs go south". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ Vanderklippe, Nathan (April 23, 2010). "Oil sands awash in excess pipeline capacity". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- ^ a b Vanderklippe, Nathan (2010-04-29). "Pipeline fees revolt widens". The Globe and Mail (Toronto). Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ a b c Hussain, Yadullah (25 April 2013). "Alberta exploring at least two oil pipeline projects to North". Financial Post.

- ^ Vanderklippe, Nathan (22 January 2013). "Oil differential darkens Alberta's budget". Calgary, Alberta: The Globe and Mail.

- ^ a b http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/globallaborinstitute/research/upload/GLI_Impact-of-Tar-Sands-Pipeline-Spills.pdf

- ^ http://www.freep.com/article/20130429/NEWS06/304290056/Enbridge-damage-Utility-road-fixes-could-hit-1-million

- ^ Editorial, Canada train disaster bolsters pipeline case: Our view, USA Today, 11 July 2013.

- ^ U.S. EIA, Williston Basin crude oil production and takeaway capacity are increasing

- ^ Diana Furchtgott-Roth, Quebec tragedy reminds us pipelines are safest way to transport oil, The Globe and Mail, 8 July 2013.

- ^ Sider, Alison. "In Dakota Oil Patch, Trains Trump Pipelines". http://online.wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Pew Center, Continued Support for Keystone XL Pipeline, 26 Sept. 2013.

- ^ Americans favor Keystone XL pipeline], 2011-03-22, Gallup Report, Rasmussen

- ^ Rasmussen Reports, 56% See Keystone XL Pipeline As Good for the Economy, 6 January 2014.

- ^ Ross, Sherwood (2012-01-05). ""Game Over" For Planet If XL Oil Pipeline Is Built". countercurrents.org. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ Radford, Philip; Hannah, Daryl (2011-08-29). "Shining Light on Obama's Tar Sands Pipeline Decision". The Huffington Post.

- ^ a b Mayer, Jane (2011-11-28). "Taking It to the Streets". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (2011-11-09). "Keystone: pipeline to Obama's re-election". The Guardian (London).

- ^ "Daryl Hannah freed following arrest in pipeline protest". Chicago Sun-Times. October 6, 2012.

- ^ James B. Kelleher (31 October 2012). "Green Party presidential hopeful arrested in pipeline protest". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Mufson, Steven (31 October 2012). "Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein charged with trespassing in Keystone XL protest". Washington Post. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (2013-02-17). "Keystone XL protesters pressure Obama on climate change promise". The Guardian (London).

- ^ http://www.politico.com/story/2013/02/thousands-rally-in-washington-to-protest-keystone-pipeline-87745.html#ixzz2LDwj7Myp

- ^ Graybeal, Susan (February 18, 2013). "40,000 People Reported at Climate Change Rally". Yahoo News. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Rafferty, Andrew. "Thousands rally in D.C. against Keystone Pipeline". NBC News. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "2.2.3 No Action Alternative", Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), Department of State, January 2014, retrieved 2 February 2014

- ^ Lee, Mike; Klump, Edward (2011-11-16). "Enbridge Plans to Reverse Pipe Between Cushing and Houston". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ Lee, Mike; Olson, Bradley (2012-05-19). "Enterprise, Enbridge Propose Keystone Pipeline Alternative". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg. Retrieved 2011-11-26z. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nichols, Bruce (2011-09-29). "Seaway pipeline sends oil to Texas in historic reversal". Reuters. Rueters. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- ^ Lefebvre, Ben (2011-11-18). "More Pipelines Needed to Follow Seaway's Path". The Wall Street Journal. (subscription required). Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ "Keystone pipeline: TransCanada to Shorten Route and Bypass Federal Review". Bloomberg. 2012-01-19.

- ^ Olson, Bradley; Lee, Mike (2012-03-22). "Obama's Speedy Keystone Review Won't Accelerate Cushing Pipe". Bloomberg.

- ^ http://www.transcanada.com/gulf-coast-pipeline-project.html

- ^ Jill Burke, Alaska watches Canadians consider shipping tar sands oil across Arctic Ocean, Alaska Dispatch, 30 April 2013

- ^ TransCanada, Energy East News Release, August 1, 2013

- ^ Enbridge website

- ^ Shook, Barbara (2009-09-18). "Independent refiner CVR sues TransCanada's Keystone Pipeline". The Oil Daily (AllBusiness.com, Inc). Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ "NRDC's Suit to Block Canada-US Oil Pipeline Thrown Out". Associated Press. 2009-10-02. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ "Enviros Sue to Stop Keystone Pipeline Project". Courthouse News Service. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keystone Pipeline. |

- Keystone Pipeline Project, TransCanada

- Keystone Pipeline Reports and Publications, TransCanada

- Keystone XL Pipeline Project: Key Issues Congressional Research Service

- Oil Sands and the Keystone XL Pipeline: Background and Selected Environmental Issues Congressional Research Service

- Study on Impact of Social Media on Keystone XL, MediaBadger.com

- Photos of 2013-02-17 Washington, D.C., March against the Keystone XL

- The Canadian Press (March 17, 2013). "Alberta lobbies for Keystone XL in New York Times ad: Influential newspaper ran editorial last week urging Obama to reject pipeline". CBC. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- It's Only the Future of the Planet; Keystone coverage treats climate change as at best a side issue coverage of media coverage in April 2013 Extra! Vol. 26 No.4 Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting

- Enbridge Line 6B Citizens' blog Citizens' Blog discusses pipeline-related issues in the U.S. and Canada

- The Keystone XL Controversy, Oil-Price.net