James Marsh, director of the poignant Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything, talks about making a movie with—and about—a living legend

It’s a very good thing director James Marsh isn’t a defeatist. If he were, he would curse the Hollywood calendar that has his compelling biopic of Stephen Hawking, The Theory of Everything, opening in the same week as Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster Interstellar. Ordinarily, an arena-scale spectacle like Interstellar and a bit of cinematic chamber music like Theory wouldn’t have a lot to fear from each other, since their audiences would be decidedly different. But that’s not so this time.

Both movies, in their own ways, wrestle with the same head-spinning questions: the mysteries of the universe and the physics of, well, pretty much everything there is. And both, in their own ways, succeed splendidly. Nolan had the far heavier lift when it came to the sheer scale of the production he was undertaking. But Marsh had the tougher go when it came to making sure his audiences sat still for the tale he wanted to tell, since he didn’t have eye-popping special effects and a thumping score to make the science go down easier. But he plays to that minimalism as a strength, keeping things small, intimate and sometimes brilliantly metaphorical.

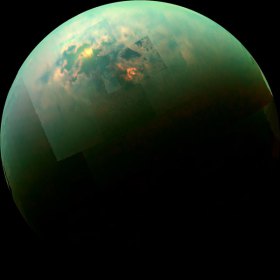

On occasion, the facts of Hawking’s own life supplied those metaphors. Even as the great physicist was descending into the black hole of an illness that would render him both immobile and mute, he discovered the phenomenon now known as Hawking radiation, a form of energy that allows information to escape from the gravitational grip of a black hole—a grip so great that it swallows even light. Hawking has spent most of his life finding his own way to get information and ideas out to the world.

And when did the young Hawking have the flash of insight that the eponymous radiation exists? While struggling to free himself from a tangled pajama top that his weakened muscles could no longer negotiate. When life throws a good director a fat, over-the-plate pitch like that, the good director hits it out of the park—and Marsh excels in that moment, as he does with the film as a whole.

Taking a break from both promoting Theory and directing a new project for HBO, Marsh spoke to TIME about getting to know Hawking, working to understand his physics, and turning what could have been a mawkish tale of sickness and survival into a movie that is equal parts drama, wit, love story and ingenious science lesson.

How difficult was it to weave hard cosmological science into a personal story about a man, his marriage and his illness?

I think of myself as a member of the general audience who comes to the movie not overly familiar with cosmology. I pitched the science at a level that I think I would understand, so audiences will too. The movie is really a story of the heart, about two people [Hawking and his wife Jane], and we give them equal screen time. There was a very interesting tension between Hawking’s scientific career on the one hand and his marriage and health on the other. They move in opposite directions, with one soaring as the other is declining. A drama wouldn’t ordinarily be the best way of exploring complex ideas like Hawking radiation, but that balance, that tension made it possible.

Cosmology is that rare science that almost no one understands but almost everyone finds fascinating. Why do you think that’s so?

These are the biggest questions imaginable. Stephen’s work is dealing with the nature of time and the boundaries of the universe. He approaches them through the lens of physics, but what he’s engaging with are the deepest mysteries we can contemplate.

How involved was Hawking in the production?

[Screenwriter] Anthony McCarten spent many years working on a screenplay and talking to Jane Hawking, whose memoir is the source of the movie. We then went to Stephen and he read the script. He wasn’t wildly enthusiastic with the idea but he agreed to cooperate. He offered us some items from his personal collection, including the medal that [his character is seen] wearing at the end of the movie. At each step of the production we involved him, consulted with him. We had a physicist—a former student of his—on the set at all times to make sure all of the equations looked right.

Did Hawking himself ever visit?

During the May Ball shoot [a scene at an outdoor dance], he came to the set with his handlers and other assistants. He was very impressed by the scale of everything, but it raised the stakes a lot when he was there, especially because it was on the same night Jane showed up. Earlier, Jane took us to the house where they lived when they were first married. She showed us the spot where Stephen was saying “I have an idea” when he was struggling with his pajamas and came up with Hawking radiation. Scientists are like filmmakers: they have the oddest ideas at the oddest times.

Did you give Hawking any kind of final approval of the film before it was released?

When it was cut but not finalized, we took the film and showed it to him as a mark of respect. Had he not liked it we would have failed, so that was very nerve-wracking. It seemed to us that he had an emotional reaction while he was watching the movie. His response afterwards was very generous. He said the movie felt ‘broadly true,’ and then he sent the company an e-mail saying that when he watched Eddie [Redmayne, who plays Hawking] perform, it was like watching himself. He also offered us the use of the real electronic voice he uses to communicate to replace the one we were using. It has a weird emotional spectrum and it made the movie better. It felt like an endorsement.