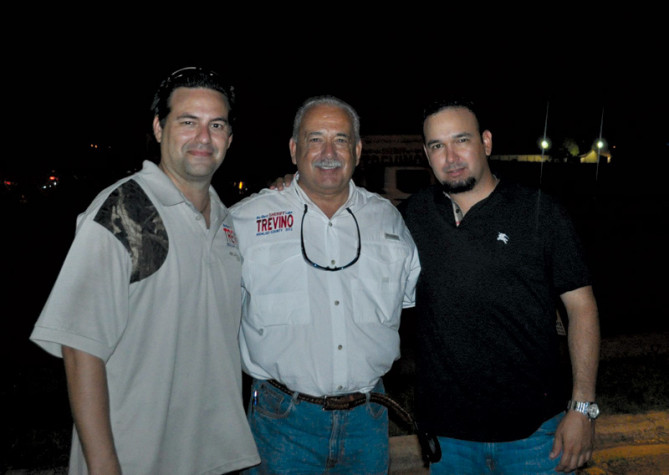

After the sudden—yet not entirely surprising—resignation Friday of embattled Sheriff Lupe Treviño, Hidalgo County moved quickly to appoint an interim sheriff Wednesday. The Hidalgo County Commissioner’s Court appointed Precinct 4 Constable J.E. “Eddie” Guerra to run the law enforcement agency, one of the largest in the state with nearly 800 employees and a $44 million budget.

County residents will have an opportunity to elect a new sheriff in the November general election. The Monitor in McAllen reported that 12 candidates applied to replace Treviño as interim sheriff and there were three finalists up for consideration Wednesday. Guerra, the only elected official in the running, was chosen by unanimous vote after about 25 minutes of deliberation.

The 52-year-old Guerra will resign from the constable position immediately and begin serving as sheriff Thursday. “The message that I really want to give out is that we’re going to start restoring accountability back to the Sheriff’s Office,” Guerra said, according to The Monitor. “We’re going to hold these people accountable—the deputies accountable for their actions—from now on. We’re not going to make any excuses for any troubles.”

Treviño, in his resignation letter submitted to County Judge Ramon Garcia last week, said that Texas’ “eighth largest sheriff’s office deserves dedicated and focused attention which I have not been able to give it.” The 65-year-old has dealt with a series of scandals since ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations and the FBI arrested his son Jonathan Treviño, a former Mission police officer, in December 2012. Jonathan and other officers associated with the Panama Unit—including five Hidalgo County deputies—were indicted for “conspiring to possess with intent to distribute” cocaine, marijuana and methamphetamine.

Shortly after the Panama Unit bust, James Phil “JP” Flores, who ran the sheriff’s Crime Stoppers program, and 47-year-old warrants deputy Jorge Garza were also indicted along with Aida Palacios, an investigator with the district attorney’s office. According to federal indictments, the drug conspiracy centered on local drug dealers Fernando Guerra Sr. and his son Fernando Jr.—also indicted—who helped set up fake drug stings with the corrupt cops to rip off other local dealers and then sell their drugs.

In December of 2013, Treviño’s management of the law enforcement agency was dealt yet another blow when Commander Jose “Joe” Padila, a close ally and integral part of the sheriff’s re-election campaigns was indicted for drug trafficking and money laundering in connection with a known Weslaco drug trafficker, Tomas “El Gallo” Gonzalez. Padilla has pled not guilty and is still awaiting trial.

Treviño received two $5,000 cash donations from “El Gallo” Gonzalez. Treviño told The Monitor that Padilla had delivered the campaign donations but that he rejected the money. Gonzalez also paid for campaign re-election signs for Treviño.

Federal agents don’t seem close to ending their investigation, which only spells more trouble for the embattled Treviño who, to date, has not been charged with any crime. On March 10, Texas Rangers and federal agents executed a search warrant at the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s office and confiscated a computer. Two weeks later Treviño’s Chief of Staff Maria “Pat” Medina resigned for “personal reasons.” Medina is also Treviño’s campaign treasurer.

Treviño’s replacement, Guerra, will be sworn in tomorrow. Guerra has worked in Hidalgo County law enforcement since 1995. He has also worked as a reserve deputy for the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Office. In a press release sent out late Wednesday, Guerra called his new appointment “nerve racking” but said he feels he can make a difference at the troubled sheriff’s agency.

“My first order of business tomorrow after I submit my bond and I am officially sworn into Office; is to address the hard working men and women at the Sheriff’s Office,” he said. “I am going to challenge them to work with me to regain the public’s trust and admiration and lift the dark cloud over the Sheriff’s Office.”