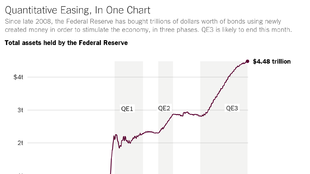

Quantitative Easing Is Ending. Here’s What It Did, in Charts.

The program has slowly helped the economy recover, but it has had many side effects, including making lots of people on Wall Street wealthy.

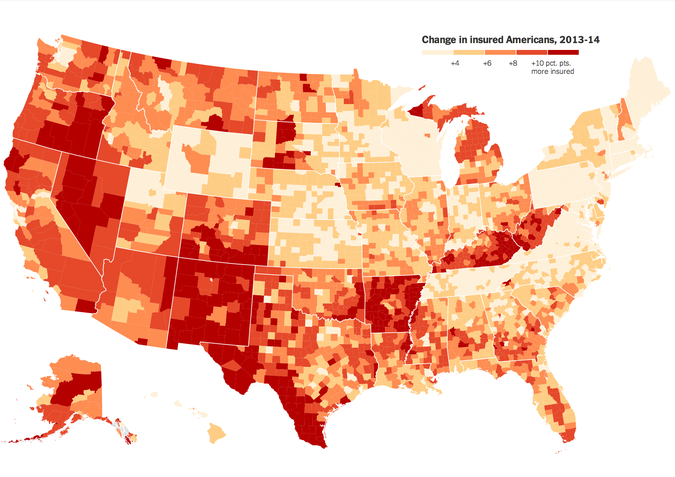

Obama’s Health Law: Who Was Helped Most

By KEVIN QUEALY and MARGOT SANGER-KATZ

A new data set provides a clearer picture of which people gained health insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

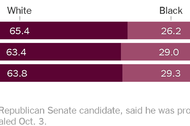

The Big Role of Black Churches in Two Senate Races

Early voting on Sundays has been one of the biggest fronts in the voting wars of recent years. Some of this past Sunday’s early voting numbers make the reason quite clear.

Data from two states that permit Sunday early voting, Georgia and North Carolina, show that 53 percent of the 25,000 early votes cast on Sunday were from black voters, compared with 27 percent of early voters across the two states since voting began for this year’s midterm elections.

“Souls to the Polls” drives are a big part of the explanation. Black churches often promote voting after services, sometimes even taking church members directly to the polls. Such drives are traditionally most popular on the Sunday before an election, when black turnout might be even higher than it was on Sunday.

A good portion of these voters would have probably cast ballots anyway. But given the margins that Democrats run up on Sundays, it is not hard to see why so many Republican election officials have sought to restrict early voting on Sundays.

Florida and Ohio moved to limit early voting on Sundays before the 2012 presidential election. (Florida has since reinstated early voting; Ohio will allow voting the weekend before the election.) North Carolina no longer has early voting on the Sunday before the election — this past Sunday was the only Sunday for in-person early voting there this year.

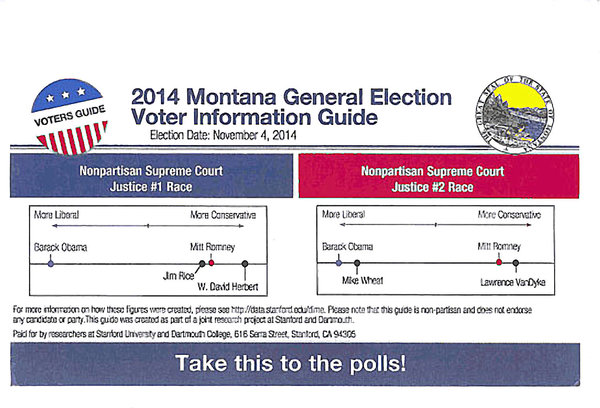

Professors’ Research Project Stirs Political Outrage in Montana

The only thing that three political scientists wanted to do was send mailers to thousands of Montana voters as part of a study of nonpartisan elections. What could possibly go wrong?

A lot, judging from the outrage and a state investigation. It has also raised thorny questions about political science field research, which isn’t uncommon, and its ability to affect an election.

The experiment, by the political scientists Adam Bonica and Jonathan Rodden of Stanford University and Kyle Dropp of Dartmouth College, sent mail to 100,000 Montana registered voters about two elections for the state’s supreme court. The Montana mailer, labeled “2014 Montana General Election Voter Information Guide,” featured the official state seal. It also placed the four judicial candidates on an ideological spectrum that included Barack Obama and Mitt Romney as reference points.

The mailers were designed to test whether voters who received information placing candidates on an ideological range would be more likely to vote. While political scientists have studied partisan races and voter turnout, less is known about nonpartisan races. Mr. Bonica, who had developed ideological scores for candidates and campaign donors, created a similar measure for state supreme court justices. The ideological scores for the Montana nonpartisan candidates were based in large part on the partisan candidates their donors had also given to. (The Upshot has written about Crowdpac, a start-up that Mr. Bonica is involved in.)

By putting the four candidates on an ideological range, the experiment also raised the ire of Montana officials, who expressed concern about the injection of partisanship into an officially nonpartisan race. “For a university to join in the flood of outside groups coming into Montana is not doing a service to our democracy,” said Senator Jon Tester, a Montana Democrat, in a telephone interview. He said the experiment was done “to influence voters” and described the mailer’s language as “the kind of stuff I get from the Montana Republican Party or Democratic Party.”

The use of the state seal also upset officials because it cannot be used on campaign literature. Groups wishing to use it must obtain the permission of the Secretary of State. Montana officials have begun an investigation into the mailers’ display of the official seal. Montana’s commissioner of political practices, Jonathan Motl, has asked Stanford and Dartmouth to disavow the mailers.

Stanford and Darmouth have jointly sent an open letter to voters apologizing for the mailer, and both are now investigating the project.

Senator Tester also said he would examine if any federal money had been used to pay for the study. (It was funded by a grant from the Hewlett Foundation and from Stanford itself, although the university has not detailed the source of that money).

The sharp reaction has veered into questions of whether the researchers were out to favor one candidate or another or whether the experiment was some kind of test of Crowdpac’s business.

Political scientists conduct field experiments to assess voter turnout in every election cycle. There is a large and growing body of work about the most effective methods for reaching voters and mobilizing them to vote, and field experiments are common.

Harvard political scientists have examined the effect of independent groups on ballot initiatives, for example, and like the Stanford-Dartmouth study, did so during a real election. The political scientists send different messages to different voters to test their effectiveness, a practice also used by political operatives. As John W. Patty, professor of political science at Washington University in St. Louis, put it, aside from using the state seal, “nothing that the researchers did would be inadmissible if they had just done it on their own as citizens.”

The size of this experiment — with mailers sent to nearly 15 percent of Montana’s registered voters — might be perceived as a large enough sample to directly sway the outcome. But nearly all field experiments conducted during elections affect the outcome in some way.

Melissa Michelson, a political science professor at Menlo College in California, said in a telephone interview that it could “poison the well” for future field experiments by making it harder to get institutional approval.

“Most of the time, experiments are nonpartisan or done in conjunction with an organization or campaign,” she said. The Montana mailers were not, she said, and “they made it look too official” by using the seal. Ms. Michelson, who wrote about the controversy on a political science blog, said adding ideological measures to the mailers was likely to raise the hackles of voters in the West. “Out here, that’s just not how we do judicial elections.”

Nonpartisan elections of judges have been seen as a way of reducing the influence of politics in the judicial system. But there is research that shows that voters are able to figure out partisan affiliations in such elections, although they err more often than in a partisan contest. Other studies have found that judges have similar characteristics whether selected in partisan or nonpartisan contests, weakening the argument that nonpartisan elections result in jurists of higher quality.

It’s well established that nonpartisan judicial elections are associated with lower turnout and lower voter information than partisan contests. Montana fits this pattern: In 2010, a state supreme court race drew about 47,000 fewer votes than a statewide partisan race for Congress in a state with fewer than 700,000 registered voters. The Stanford-Dartmouth experiment was aimed at seeing whether that gap could be narrowed by providing randomly selected voters with additional details about the candidates.

“We don’t have a lot of information about campaigning in these kinds of races until about 2002,” said Melinda Gann Hall, a political science professor at Michigan State University who studies state judicial elections. Since voters often take their cues from party affiliation, the lack of that information on nonpartisan ballots can make any independent information, whether advertisements or voter guides, more important, she said.

The controversy may have the result of raising the profile of the state supreme court contests, even possibly increasing voter turnout in Montana.

But someone else will have to study that.

Senate Model Update: What if Georgia Goes to a Runoff?

After new waves of battleground polling from both YouGov and Marist pushed Republican chances of winning control of the Senate from 64 percent to 68 percent on Sunday, things inched toward the G.O.P. yet again Tuesday, with Republicans now having a 70 percent chance to win.

Much of the change over the past couple of days can be traced to South Dakota, where it now appears less likely that the Republican candidate, the former governor Mike Rounds, will fall victim to an upset in the three-way contest. Although some earlier polls had shown the independent candidate, the former senator Larry Pressler, securing as much as 32 percent of the vote, the latest figures suggest that Mr. Rounds may be pulling ahead, and our forecast now gives him a 98 percent chance to win next week.

While our forecast in Georgia remains mostly unchanged, with the Democratic candidate Michelle Nunn having a 48 percent chance of beating the Republican David Perdue, it’s how we're getting to that 48 percent that's now changed.

Over the past few weeks, polling has shown Ms. Nunn steadily closing in on Mr. Perdue. Various pundits have cautioned that Ms. Nunn’s chances may be lower than they might appear because of the Libertarian candidate, Amanda Swafford, and Georgia’s requirement that the race go to a runoff if no candidate gets more than 50 percent of the vote.

In order to avoid a runoff, the winning candidate’s margin of victory has to exceed Ms. Swafford’s share of the vote. Given how close the race is (the current forecast has Mr. Perdue winning by one fifth of a percentage point), this could seem doubtful. Libertarians in previous Georgia Senate contests have been remarkably consistent: With the exception of Claude Thomas, who earned only 1.3 percent of the vote in 2002, the Libertarian candidate has drawn between 2 and 4 percent of the vote in every Georgia Senate election since 1992. True to form, Ms. Swafford’s poll numbers have shown her support hovering around the 4 percent mark.

The Upshot model now includes an explicit forecast for the likelihood that neither Michelle Nunn nor David Perdue crosses the 50 percent threshold, sending the race to a runoff election in January. As the margin in Georgia has shrunk over the past few weeks, the possibility of a runoff has grown. Our latest forecast puts the chance of a runoff at 66 percent.

From a forecasting perspective, the probability of a runoff is only half the question. The hard part is how we ought to assess the major-party candidates’ chances in a runoff election.

One approach would be to look at previous runoffs in Georgia, an approach that doesn’t give much comfort to the Nunn campaign. Georgia has had five previous statewide runoff elections. There were two in both 1992 and 2008 — each time for senator and for public service commissioner — and one in 2006 for public service commissioner. In all five of those elections, the Democrat lost. Using this information, we could assume that the future will repeat the past exactly, and assign Ms. Nunn a zero percent chance in a runoff.

Of course, we’re not entering this cycle completely blind. We have plenty of information about the two campaigns in the form of general-election polling. We could use these polls by apportioning the Swafford voters among Ms. Nunn and Mr. Perdue according to how we think they would vote in a runoff. But that would require additional assumptions about how the Swafford supporters might vote.

It might be better not to apportion them at all, though as a practical matter this has the same effect on the polling margin as dividing them evenly between the two campaigns. (This is a small example of how making a decision not to make any assumptions often brings with it its own set of assumptions.)

But regardless of how — or whether — we apportion Swafford voters, this approach doesn’t really capture the dynamic at play in a runoff election. The campaigns aren’t merely reapportioning third-party voters between them. They’re drawing votes from an entirely different electorate than the one that comes out to vote in November.

In previous Senate runoffs, turnout varied between 55 and 57 percent of general-election turnout (in 2006, when the runoff was for the public service commissioner alone, turnout declined by a factor of 10). In other words, it’s less about attracting third-party voters to your side and more about voter motivation and get-out-the-vote efforts. It is doubtful that a likely-voter model designed for the general election will accurately reflect the composition of the runoff electorate as well.

The few head-to-head polls that have been released suffer from this same problem. The two-party preferences of the November electorate are next to irrelevant in trying to model the outcome of an election held among a very different set of voters.

The forecasting gets even more complicated. A Georgia Senate runoff election wouldn’t be held until Jan. 6 — three days after the 114th Congress convenes. That timeline is important because it is entirely possible that control of the Senate would still not be decided by then. If it all rested on the outcome of the runoff in Georgia, both parties would be cranking hard to turn out as many voters as possible. Such a situation would undermine any pre-election turnout forecasts.

But hold on! There is yet another twist. It remains very possible that the Georgia governor’s race will go to a runoff as well. If it did, that election would be held in December, raising the very real possibility of voter fatigue.

With so many variables working to dilute and degrade the data we would use to forecast a January runoff, we think it’s not unreasonable to treat the runoff forecast with zero information, and assign each candidate an even chance. (Various principles of statistical reasoning suggest that, in the absence of other information, a prudent choice for your model is one that maximizes the amount of uncertainty — or, in the language of information theory, entropy.)

The practical effect of increasing the amount of uncertainty we have about the outcome of the race is like attaching a weight to our forecast that pulls it back toward 50 percent. Over the next few days, it’s possible that Mr. Perdue or Ms. Nunn will pull into the lead, and this uncertainty will decrease. But all indications are that the race in Georgia will remain close right up until Election Day, and quite possibly, for a few months beyond.

Here’s some of our best and most popular interactive work about politics and the economy:

We also like sports. Here's some of our best stuff on that topic:

More Posts

Enroll America began with a huge phone survey of 12,000 adults and added neighborhood data.

Although the example of Michael Bennet’s unlikely election in 2010 looms large in this race, the two situations are quite different.

The chances for the incumbent senator to hang on to his seat suddenly look brighter.

Michael Bloomberg’s charity announced an effort to reduce the number of poor students who excel in high school and fail to get through college.

We calculate a new index — the Matty Score — to rank the top pitchers in World Series history. Madison Bumgarner joins Christy Mathewson, Sandy Koufax and others.

The purchase of one of the most costly apartments in New York for speculative purposes is a good example of a deal that does nothing for the economy.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been hailed as a leader on H.I.V. prevention, but many of his allies on that issue are upset about his handling of Ebola.

Getting answers on how to grade the health act will take time, but here are the right questions.

Michelle Nunn has caught up to David Perdue in polling, and her gains can be attributed to changes in the racial composition of likely voters.

Political ads on TV, though much loathed, actually do the job of improving awareness of who is running for or holding office.

About the Upshot

The Upshot presents news, analysis and data visualization about politics and policy. It will focus on the 2014 midterm elections, the state of the economy, upward mobility, health care and education, and occasionally visit sports and culture. The staff of journalists and outside contributors is led by David Leonhardt, a former Washington bureau chief and Pulitzer Prize winner for his columns about economics.