We found chemical weapons my first week in Iraq.

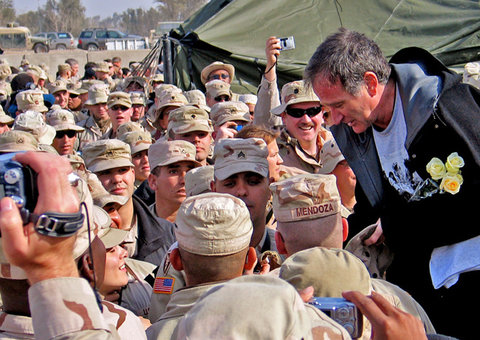

At Contingency Operating Base Speicher, I was a lieutenant working in the operations department for an explosive ordnance disposal battalion. We were responsible for the entire northern sector of the country, about 50,000 square kilometers (or roughly 19,300 square miles) of ground touching the Syrian, Turkish and Iranian borders.

The information came to me in an otherwise benign email, alongside the dozens of field reports that hit my inbox every hour. After just a couple of days as the new guy on the team, the reports showing the aftermath of vehicles and soldiers torn apart by explosives started feeling routine. I’d been expecting them.

But this one showed something I didn’t see coming: M110 shells, which are American-designed 155-millimeter artillery projectiles. These had tested positive for sulfur mustard, a blister agent.

“Chem rounds.”

I looked away from my screen, and not 10 feet away from me was Chuck, an Army E.O.D. technician who’d already served tours in Kosovo and Afghanistan. He was the kind of noncommissioned officer every lieutenant hopes for: a smart, talented young soldier who trained you up and made you better. I was already relying on Chuck for everything.

Here, I turned to him in disbelief.

I told him that the team had found chem M110’s and that the shells had tested positive for mustard.

He was unimpressed.

I persisted. As far as I knew, we’d just made the first “WMD find” of the war.

But it turned out there was a lot I didn’t know.

He cut right to the chase.

Chuck turned to me and peered over the eyeglasses low on his nose. He looked at me for a while without blinking.

“LT, let me let you in on something,” he said. “We find three or four of those things a week up north here. Everybody knows about them. And nobody cares.”

I was stunned. “You got to be kidding me.”

“Nope.”

As good noncommissioned officers do, Chuck got me up to speed quickly but also didn’t hesitate to give me swift reality checks when needed. This was one of those times.

Read more...