National health care experts want to know whether the history of infection control failures by two Dallas medical institutions was considered before they were entrusted to operate a new Ebola treatment center.

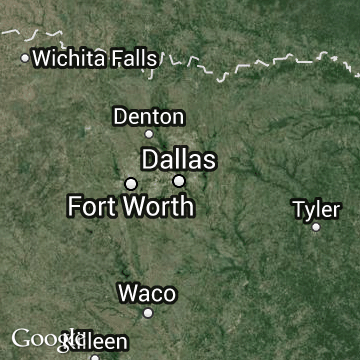

In a rapid series of events in recent days, Gov. Rick Perry’s Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response put UT Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Memorial Hospital at the helm of the 10-bed Richardson facility.

“Public confidence demands to know how this decision was made,” said Paul Levy, a former Boston hospital CEO and analyst of patient safety and hospital transparency.

“It may be the right decision, but there will always be concern and second-guessing unless the rationale is made clear, especially given the clinical history of these two institutions.”

Until late last year, Parkland and UTSW were at the center of rare government safety intervention to try to fix what regulators called life-threatening breakdowns in infection control and other practices throughout Parkland, Dallas’ tax-funded public hospital. UTSW manages clinical care at the facility.

Regulatory violations have ranged from poor hand washing to filthy patient rooms with overflowing trash bins, excrement and blood. Turf battles between the two organizations over money, physician staffing and their divergent missions also have been factors in jeopardizing patient care over the years, a 2013 investigation by The Dallas Morning News found.

But state officials including the governor’s office aren’t saying whether the stormy partnership or regulatory violations came into play during their quick effort to establish the Ebola center.

“Parkland and UT Southwestern work together every day to care for patients, and they’ve already been training for the strict infection control procedures needed to handle a patient with Ebola,” said a spokeswoman for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which co-ordinates the task force that made the decision.

The commission declined to answer detailed questions about the decision. It gave the institutions a vote of confidence.

“I have heard not one concern [among task force members] about the ability of these two institutions to run an effective center,” said Stephanie Goodman, the commission spokeswoman.

Dr. Ashish Jha, associate professor at Harvard University’s School of Public Health, said the public needs an explanation.

“It’s absolutely important for them to address this publicly,” Jha said. “A big question is: Have they [Parkland and UTSW] really put these problems behind them, and do they understand what caused them?”

Last year, the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ended two years of onsite safety monitoring at Parkland after the hospital spent nearly $100 million on reforms. Its executive team was replaced, and the hospital passed a final sweeping inspection.

UTSW doesn’t answer to CMS for Parkland violations because it is not the hospital’s actual license holder or direct recipient of operational funds.

But Parkland remains under close scrutiny by Texas regulators through a settlement stemming from a record $1 million state fine for its infection control lapses and other failures.

The hospital is due for another surprise comprehensive inspection after authorities found more recent care breakdowns, including a case where staffers gagged a patient with a toilet roll and another caregivers failed to safely move a woman who couldn’t bear weight on her legs, breaking her ankle.

That inspection also will examine the hospital’s progress in remedying infection risks — a critical test of whether the 2013 fixes have been sustainable.

Parkland and UTSW would have to work together closely at the small unit now ready for Ebola patients on an empty floor of the facility at the Methodist Campus for Continuing Care in Richardson.

In a setup similar to the one they have at Parkland’s main campus, Parkland is to provide a team of nurses and other support staff, while UTSW will provide the doctors.

“But for this new Ebola center to work, effective coordination is critical,” said Ranga Ramanujam a Vanderbilt University professor who studies organizational factors related to patient safety. “As recently as a couple of years ago, audits found serious problems in the how UTSW and Parkland were coordinating their activities. It is unclear how much progress has been made in addressing these problems.”

The hospital and UTSW have declined to talk about what they have done to address their history of bitter relations, which executives have at times characterized as a “cage match” and marred by “vitriol.”

Ramanujam called the effort to channel several organizations’ resources — Methodist Health System is volunteering the space — into creating a new Ebola treatment facility “a welcome and logical solution.”

“You would assume that the task force recognized the recent history and concluded that the two organizations will be able to work beyond past differences,” Ramanujam said.

This week, Parkland and UTSW issued a joint statement praising their “70-year history of working as partners and a productive and constructive relationship.”

“Any assertion to the contrary is simply incorrect,” the statement said. “As we face this public health crisis, now is a time for unity, and we would hope that everyone would support this effort.”

Jha, who has previously criticized a lack of transparency from Parkland about patient care problems, said the organizations risk eroding the public’s confidence by staying mum about details of their relationship.

They shouldn’t fall into the same trap that Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas did, he said, where a lack of transparency in the opening weeks of the arrival of Ebola in Dallas was “shockingly bad in terms of management.”

“You want to create a certain level of confidence with the public,” Jha said. “You want to be forthright about each other with the public and what you’ve learned.”

Goodman, the state health commission spokeswoman, said it’s important to note that the Ebola center will be a much different setting than a busy hospital, with fewer organizational complexities.

“It’s a specialized unit where there will be a greater focus (on an individual or small number of patients),” Goodman said. “It’s a whole different level of care.”