When the first Ebola patient showed up at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, a warning sounded that other hospitals needed to prepare space for a possible influx of new cases.

Methodist Health System quickly identified a place that might work — a small intensive-care unit in its Methodist Campus for Continuing Care in Richardson. The unit had been empty since April but needed only minor alterations to give medical staffers room to change in and out of the protective gear required for treating Ebola patients.

“Initially, we thought it would be just for us,” said Dr. Sam Bagchi, Methodist’s senior vice president and chief quality officer.

Then came telephone calls from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dallas County and the Texas health department. Officials wanted to see what Methodist was planning and find out how quickly an Ebola treatment center could be set up.

The idea was to meet the needs of all local hospitals in one location.

The nation’s first patient diagnosed with Ebola, Thomas Eric Duncan, had died Oct. 8 at Presbyterian. Two nurses who became infected while caring for him were airlifted to specialty treatment sites in other states.

And the clock was ticking for more than 125 people locally who had been isolated because of possible exposure to the deadly disease. If any of them started showing symptoms, there had to be a treatment center ready to provide immediate care.

“All of the hospitals were working on plans to take care of an extended stay by an Ebola patient,” Bagchi said. “Why not combine those efforts? It’s meant to take the pressure off the community.”

It took only a few days for Methodist to revamp its plan into a 10-bed Ebola treatment center. Parkland Memorial Hospital agreed to supply protective gear along with a team of nurses, lab technicians and other support staff. UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas would provide overall leadership, as well as physicians and nurses.

Dr. David Lakey, the state health commissioner, toured the Richardson facility with CDC officials, said Stephanie Goodman, a spokeswoman for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission.

On Wednesday, the first two beds were ready for Ebola patients, allowing Methodist to officially activate the unit.

The facility has two negative-pressure rooms — rooms equipped to prevent the escape of contaminated air.

‘Nice collaboration’

If anyone is confirmed to have Ebola, it would take 12 hours to activate the facility and get it fully staffed. In all likelihood, an Ebola patient would have gone first to a hospital emergency room and been isolated and tested before being transferred to the Richardson facility, Bagchi said.

“This unit is for patients who test positive for Ebola,” he said. “Any patient would go through diagnostic screening before being transferred here.”

The state’s second Ebola treatment facility, at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, is expected to be ready for patients as early as Thursday. The hospital is home to the Galveston National Laboratory, a federal biocontainment facility that has extensively researched Ebola and other infectious diseases.

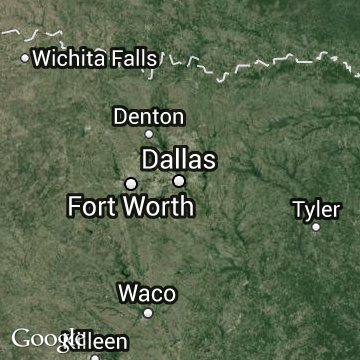

The Methodist Ebola center is on the third floor of the 51-year-old Methodist Richardson Medical Center at 401 W. Campbell Road. The hospital was replaced last spring by a new facility at Renner Road and the Bush Turnpike.

“We couldn’t have done it without the CDC’s involvement,” Bagchi said of the quick turnaround at the Methodist center. “It’s a really nice collaboration, where everybody is bringing something.”

Some experts outside Dallas questioned having UT Southwestern and Parkland involved together with the new Ebola treatment facility. The two came under federal scrutiny three years ago over lapses in infection prevention and other care.

“This track record of problems is, of course, concerning,’’ said Dr. Ashish Jha, an associate professor at Harvard University’s School of Public Health. “Have they really put these problems behind them, and do they understand what caused them?”

Parkland and UTSW declined Wednesday to answer questions about their past collaborations. In a joint statement, they spoke of their “70-year history of working as partners and a productive and constructive relationship.”

Meeting of neighbors

Wednesday evening, Richardson Mayor Laura Maczka addressed about 100 people at a regular meeting of the Canyon Creek Homeowners Association, where residents of the neighborhood just north of the hospital were agreeable to news of its designation as a treatment site.

“As a community, you hope and pray something like this never happens in your community,” Maczka said. “But if it does, you also hope and pray that you are prepared for it, and so I think we as a community should be really proud.”

Diane Jacobs, who lives near the Richardson facility, said she supported using it to care for Ebola patients.

“We’re excited that the city of Richardson can participate in this fight, because that’s what it is,” said Jacobs, who directs a church preschool.

Susan Yost, who also lives nearby, said she was “very proud” that the Richardson facility was chosen. “It makes our city more proactive and prepared. It makes me feel safer,” she said.

Rex Kathcart, another resident, said he had no concerns about the center being used as an Ebola treatment site because officials have been transparent about plans for the facility.

“I think the hospitals have learned from their mistakes,” Kathcart said. “If this was two weeks ago you may have seen some concern, but they have explained it really well.”

Texas officials said the Richardson and Galveston facilities would be available to handle outbreaks of other diseases beyond Ebola.

“Ebola is the current threat, but there are other infectious diseases that pose a risk,” said Goodman, the state Health and Human Services Commission spokeswoman. “These new centers will make sure Texas is well-prepared for whatever comes our way.”

The treatment centers aren’t costing the state any money, she said. “These hospitals already get state and federal funding, and they’re able to support the centers within their current budgets,” she said.

Treatment costs also could be billed to private insurers or Medicaid, she added.

Staff writers Leslie Barker, Julie Fancher, Wendy Hundley and Miles Moffeit contributed to this report.

sjacobson@dallasnews.com;

rloftis@dallasnews.com