By most accounts, 2010 was an outstanding year for Barolo. Based on the wine panel’s recent tasting of 20 bottles from the vintage, I have no reason to disagree.

We found many wonderful wines in our small but representative sample. But the tasting raised questions about who will be drinking wines like these and whether many of the bottles will be allowed to reach their full potential.

The conventional wisdom nowadays is that most people are unwilling or unable to age wines for long periods of time. They no longer have the money, the storage or the patience to wait years. Nor do most restaurants. As a result, many wines are made differently today than they were 30 to 40 years ago, partly so that they will not require prolonged aging to become enjoyable.

But Barolo, made entirely of the nebbiolo grape, still demands years in the cellar. In its youth, it is classically tannic and austere, but given time — often a decade or more — the tannins soften, releasing a gorgeous perfume and flavors often described as licorice, tar, truffles, violets and roses. Back in the 1980s and ’90s, a stylistic war ensued between traditionalists who sought to preserve time-honored methods for making Barolo and innovators who explored ways to make a softer, more approachable wine, sometimes at the cost of what made Barolo distinctive.

In the last 15 years, many producers have gravitated toward a middle ground, making wines in a range of styles that are still distinctively Barolo. Regardless of style, one thing is clear: Good Barolos still require many years of aging, at least to my taste. The 1996 vintage was a classic, and I still don’t think the best are ready, though the wines from softer years like 2000, or excellent, less austere years like 2001 and 2004, can already be enjoyed.

Yet most restaurants, unless they have exceptional wine lists and the wherewithal to invest for the long term, cannot wait years for a return on their Barolo investment. Often, today, you see Barolos five to seven years old on lists.

These 2010s are not nearly ready for drinking. The best are structured wines, with layers of complex aromas and flavors, but they will need time to evolve, maybe a decade or more. That will require quite the investment of patience and space — and, for those of us who may be approaching an actuarial precipice, optimism. How will restaurants handle such a vintage?

“We have the luxury of storage,” said Juliette Pope, wine director at Gramercy Tavern, one of two guests who joined Florence Fabricant and me for the tasting. Grant Reynolds, our second guest, the wine director at Charlie Bird, said restaurants can adapt to serving younger Barolos.

“I don’t mind abrasive tannin,” he said. “It’s the nature of the wines. But you have to have the right food with it.”

If you have the patience and taste for structured Barolo, these wines offer much to be thrilled about. They follow classic lines, already showing beautiful aromas of red fruit in some cases but austere and backward on the palate.

Among our sample we found few wines spoiled by the aromas and flavors of new oak, a signature of Barolo innovators who traded in the traditional large storage vessels made of Slavonian oak, which were reused year after year, for new barriques, small barrels of French oak. These barrels imparted aromas of coffee, chocolate and vanilla, along with the bitter flavors of oak tannins. Today many producers continue to use barriques, but they are smarter about it, using more older, neutral barrels that don’t inflict aromas and flavors on the wine.

Barolos are not cheap by any means, though not nearly as expensive as other benchmark wines like Bordeaux and Burgundy. Still, hype for the 2010 vintage seems sure to drive prices up. The wine panel operates with a cap of $100 a bottle, which eliminated some producers from consideration, while other top Barolos have not yet been released. So some of the greatest names, like Giacomo Conterno, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Giuseppe Mascarello, Cappellano and Bartolo Mascarello, were not in our tasting.

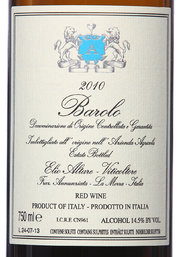

Nonetheless, we found many excellent wines, beginning with our No. 1 from Elio Altare, complex, structured, pure and nuanced. Mr. Altare has been foremost among the innovators in Barolo, often cited as a contrasting figure to the arch-traditionalist Bartolo Mascarello (the two producers were paradoxically good friends). But, even though our taste on the panel runs toward the traditionalists, we all loved this wine, which seemed classically shaped with no evidence of aromas or flavors from barriques.

No. 2 and No. 3 among our top 10 came from far less familiar names in the American market, but they are both worth seeking out. The 2010 Bussia from Giacomo Fenocchio was firmly structured, yet the resounding, high-toned flavors showed through the tannins, promising a great future. By contrast, the 2010 Paiagallo from Giovanni Canonica was fleshy, deep and more forthcoming aromatically.

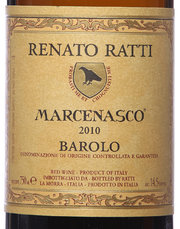

Other names among our top 10 are better known to Barolo fans. The Vigna Margheria from Luigi Pira, No. 4, was tight and tannic, though with layers of flavor, while the Vigna Casa Matè from Elio Grasso, No. 5, showed great finesse and balance. The Grasso, $95, was the most expensive bottle in our tasting. The structured yet nuanced No. 6, Marcenasco from Renato Ratti, at $43, was our best value, not cheap yet a good deal for world-class, age-worthy wine. Other producers worth seeking out include Burlotto, Barale Fratelli, Brovia, Roagna, Luigi Einaudi and A.&G. Fantino.

Cooking Newsletter

New recipes from The New York Times, delivered to your inbox three times a week.

In some ways, the greatness of Barolo and its sibling, Barbaresco, while long accepted, is only beginning to be understood. Partly, this is because clear and precise appellations, so integral to understanding Burgundy, are lacking for Barolo. It’s left to consumers to research and understand the differences among the various sub-zones. One new resource that will be a great help is Kerin O’Keefe’s authoritative “Barolo and Barbaresco: The King and Queen of Italian Wine,” just published by the University of California Press.

For consumers who cannot wait for these wines to come into their prime, there are alternatives. Nebbiolo d’Alba and Langhe Nebbiolo, produced in and around the Barolo and Barbaresco zones, will generally be accessible earlier. Northwestern Italy produces many other excellent nebbiolos that likewise won’t require as much aging. But for the true Barolo lover who will seek out these 2010s, I can only counsel patience.

An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of the No. 5 wine in the taste ranking. It is Vigna Casa Matè, not Vigna Case Matè.