07 Apr 2014: Report

On Fracking Front, A Push

To Reduce Leaks of Methane

Scientists, engineers, and government regulators are increasingly turning their attention to solving one of the chief environmental problems associated with fracking for natural gas and oil – significant leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Loose pipe flanges. Leaky storage tanks. Condenser valves stuck open. Outdated compressors. Inefficient pneumatic systems. Corroded pipes.

Forty separate types of equipment are known to be potential sources of methane emissions during the production and processing of natural gas and oil by hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, of underground shale

Tim Evanson/Flickr

"Fugitive" methane escapes from natural gas production sites, such as this one in North Dakota.

"There are many, many, many possible leaking sources," said Adam Brandt, a Stanford University professor of energy resources engineering who compiled recent estimates of the oil and gas industry’s methane emissions. "Just like a car, there are a variety of ways it can break down."

Even among industry officials, there is agreement that getting control of methane emissions is an important issue. At heart it is an engineering problem, and solutions from government, industry, and academia are beginning to take shape. Analysts say that battling the problem must occur on two closely related fronts: tighter regulations at the state and federal level, and a commitment from industry

A commitment is needed from industry to make the large investment necessary to stanch the methane leaks.to make the large investment necessary to stanch the leaks.

Last month, the Obama administration announced a plan to reduce methane emissions from a host of sources, including landfills, cattle, and the oil and gas industry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has pledged to identify approaches to cut so-called "fugitive" methane emissions from oil and gas drilling by this fall and to issue new rules by 2016 as President Obama’s term in office comes to an end. Roughly nine percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from methane.

"The strategy is a good plan of action," said Vignesh Gowrishankar, a staff scientist at Natural Resources Defense Council. "But more needs to be done. The most important thing is to ensure that EPA implements stronger standards that go after methane directly and include existing equipment in the field because that is what is leaking."

Colorado, a major oil and gas producer, in February became the first state to impose regulations requiring producers to find and fix methane leaks. And as public concerns mount over the environmental fallout from the fracking boom, even states such as Texas are examining whether to adopt tighter methane regulations.

Industry has lived with methane leaks, despite the value of capturing and eventually selling the methane, because of the expense involved in stopping fugitive emissions. Fixing the problem would require a comprehensive approach that would involve not only detecting methane leaks, but also instituting a host of engineering and mechanical fixes along the entire

Solving the problem would require a host of fixes along the entire production chain.chain of production and processing, from the wellhead to pipes.

Reducing fugitive methane emissions can be classified into easy fixes, such as tightening pipe flanges, to harder ones such as replacing valves in compressor stations that constantly pump gas under intense pressure, said Bryan Willson, program director at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E).

There is less incentive for the industry — particularly smaller, cash-constrained companies — to make fixes that require more personnel, time, and money, yielding a lower return-on-investment. Some of the fixes, such as "vapor recovery units" that prevent gas from volatilizing from storage tanks, come with a price tag of $100,000 each, said Gowrishankar. One study found storage tanks to be a significant source of volatile organic compounds and methane emissions in Texas’ Barnett Shale region.

A key question is whether the U.S. can achieve a significant reduction in methane emissions as the fracking boom continues to expand and older equipment becomes more prone to problems. With close to 500,000 hydraulically fractured gas wells alone and hundreds of thousands of miles of pipelines, just figuring out the scope of the problem, let alone fixing all the leaks, is a daunting challenge, experts say.

Calculating exactly how much methane is escaping during the fracking and processing of oil and gas is exceedingly difficult. Estimates of methane emissions range from 1.5 percent to 9 percent. Getting a clearer sense of the scope of the problem is vital; although methane only lingers in the atmosphere for 10 to 20 years — as opposed to hundreds of years for carbon dioxide — recent studies show that methane is 34 times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2. Failing to stop widespread methane leaks from the

A study found leaks of methane from drilling sites were 50 percent higher than previously estimated.global oil and gas industry in the coming decades could significantly exacerbate global warming, many experts say.

With an expected 56-percent increase over the next 25 years in U.S. natural gas production alone — most of which is expected to come from fracking — the problem of methane leaks is going to get worse "unless we make the investment" in lower-emissions technology, said Michael Obeiter, a senior associate in the climate and energy program at the World Resources Institute.

In February, Brandt and 15 co-authors published a paper in Science, based on a review of more than 200 previous studies, concluding that leaks of methane from drilling sites were 50 percent higher than previously estimated by the EPA. "A variety of evidence" points to emissions higher than 1.5 percent, Brandt said.

Environmental groups such as the World Resources Institute, Environmental Defense Fund, and the Natural Resources Defense Council

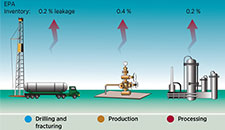

MIT Energy Initiative

Methane leaks occur at all stages natural gas production, processing, and transport.

Methane emissions from oil and gas drilling are broken down into two different problem areas. The first is outdated equipment that emits much more methane than newer, low-emissions technology. The second is a string of leaks in the system, many which can be difficult to detect. "If we can develop a way to find these leaks cheaply, frequently, and in an automated fashion," most of the leaks can be detected and fixed, said Brandt.

Obeiter lists two major equipment upgrades that have already shown promise in the field, but have not been widely adopted by industry.

The first is the use of plunger lift systems at new and existing wells during "liquids unloading," which are operations that clear water and other liquids from the system. The second is replacing existing high-bleed pneumatic devices with low-bleed equivalents throughout natural gas systems.

Some companies such as Encana — a natural gas producer that has 4,000 gas wells in Colorado — are retrofitting outdated equipment prone to leaking, and installing technology to capture leaks at the wellhead. The company began replacing existing high-bleed pneumatic devices before the conversion was mandated in Colorado’s new regulations, said Doug Hock, a spokesman for the company. Hock calls the new rules in Colorado "tough but reasonable" and says they provide the industry in the state with regulatory certainty going forward.

But even if every state mirrored Colorado and every oil and gas company took steps such as Encana is taking, a significant amount of methane would still be leaking — and much of it undetected, says Mark Zondlo, a professor of engineering at Princeton University. That’s because many methane leaks

There is a lot of guessing by industry about where and how often leaks occur, an expert says.are caused by more erratic and episodic factors, such as a valve or storage-tank hatch suddenly stuck open. Hence the need for "continuous measurements" for methane leaks across large areas, Zondlo said.

Currently, there is a lot of "guessing" on the part of the industry and researchers as to where and how frequently the majority of leaks are happening, says Zondlo.

Industry representatives say the methane leakage rate is at the low end of estimates, about 1.5 percent, placing industry second behind emissions attributed to livestock, said Katie Brown, spokesperson for Energy in Depth, a program of the Independent Petroleum Association of America.

To achieve climate benefits from natural gas, environmental groups estimate the leakage rate during gas drilling must remain below 1 percent. "Cutting methane leakage rates from natural gas systems to less than 1 percent of total production would ensure that the climate impacts of natural gas are lower than coal or diesel fuel over any time horizon," Obeiter said.

But Sandra Steingraber, an environmentalist and scholar in residence at Ithaca College, compares chasing methane leaks and retrofitting old equipment to "putting filters on cigarettes." She said that even reducing methane leaks by 30 to 40 percent will be too little too late to help slow climate change, especially as the industry expands.

Currently, many companies are using methane-leak detection tools, such as infrared cameras, that are too labor-intensive and fail to find many

MORE FROM YALE e360

As Fracking Booms, Growing

Concerns About Wastewater

READ MORE

Zondlo recently developed a methane sensor mounted on a remote–controlled aircraft built at the University of Texas at Dallas. In October, the aircraft was used to quantify emission rates from well pads and a compressor station in the Barnett Shale region. Zondlo has been partnering with other groups that fly drones over fracking areas to detect leaks.

Robert B. Jackson, an ecologist and energy expert at Duke University, also has been testing drones to detect fugitive methane emissions. The main drawback, he says, is the payload. "Carrying a big camera or methane sensor, a drone might be able to stay in the air for 30 minutes," says Jackson. "It’s difficult to screen a shale play with that kind of time."

Engineers are trying to develop lighter sensors that will allow drones to stay in the air longer. "I’m very bullish long-term on using drones to measure leaks," Jackson said. "Are we there yet right now? No."

In the Pinedale Anticline natural gas field in Wyoming, Shane Murphy and Robert Field of the University of Wyoming recently outfitted a Mercedes Sprinter van with a mass spectrometer and other high-powered scientific instruments to measure volatile organic compounds and methane. When combined with meteorological instrumentation and sophisticated software, these technologies can detect methane plumes and quantify emission rates from specific sources — all from inside the van. The equipment records readings every half-second, which allows it to be used on the move. "This approach can cover a lot of ground," Field said.

POSTED ON 07 Apr 2014 IN Biodiversity Business & Innovation Climate Energy Science & Technology Antarctica and the Arctic North America

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHORRoger Real Drouin is a journalist who covers environmental issues. His articles have appeared in Grist.org, Mother Jones, The Atlantic Cities, and other publications. Previously for Yale Environment 360, he wrote about growing concerns surrounding fracking wastewater.

RELATED ARTICLES

A Scourge for Coal Miners

Stages a Brutal Comeback

Black lung — a debilitating disease caused by inhaling coal dust — was supposed to be wiped out by a landmark 1969 U.S. mine safety law. But a recent study shows that the worst form of the disease now affects a larger share of Appalachian coal miners than at any time since the early 1970s.

For Cellulosic Ethanol Makers, The Road Ahead Is Still Uphill

While it has environmental advantages over other forms of ethanol, cellulosic ethanol has proven difficult to produce at commercial scale. Even as new production facilities come online in the U.S., a variety of economic and market realities suggest the new fuel still has big challenges to overcome.

Innovations in Energy Storage Provide Boost for Renewables

Because utilities can't control when the sun shines or the wind blows, it has been difficult to fully incorporate solar and wind power into the electricity grid. But new technologies designed to store the energy produced by these clean power sources could soon be changing that.

With the Boom in Oil and Gas,

Pipelines Proliferate in the U.S.

The rise of U.S. oil and gas production has spurred a dramatic expansion of the nation's pipeline infrastructure. As the lines reach into new communities and affect more property owners, concerns over the environmental impacts are growing.

He's Still Bullish on Hybrids,

But Skeptical of Electric Cars

Former Toyota executive Bill Reinert has long been dubious about the potential of electric cars. In an interview with Yale Environment 360, he talks about the promise of other technologies and about why he still sees hybrids as the best alternative to gasoline-powered vehicles.

MORE IN Reports

A Scourge for Coal Miners

Stages a Brutal Comeback

Black lung — a debilitating disease caused by inhaling coal dust — was supposed to be wiped out by a landmark 1969 U.S. mine safety law. But a recent study shows that the worst form of the disease now affects a larger share of Appalachian coal miners than at any time since the early 1970s.

For Cellulosic Ethanol Makers, The Road Ahead Is Still Uphill

While it has environmental advantages over other forms of ethanol, cellulosic ethanol has proven difficult to produce at commercial scale. Even as new production facilities come online in the U.S., a variety of economic and market realities suggest the new fuel still has big challenges to overcome.

Innovations in Energy Storage Provide Boost for Renewables

Because utilities can't control when the sun shines or the wind blows, it has been difficult to fully incorporate solar and wind power into the electricity grid. But new technologies designed to store the energy produced by these clean power sources could soon be changing that.

Albania’s Coastal Wetlands:

Killing Field for Migrating Birds

Millions of birds migrating between Africa and Europe are being illegally hunted on the Balkan Peninsula, with the most egregious poaching occurring in Albania. Conservationists and the European Commission are calling for an end to the carnage.

Drive to Mine the Deep Sea

Raises Concerns Over Impacts

Armed with new high-tech equipment, mining companies are targeting vast areas of the deep ocean for mineral extraction. But with few regulations in place, critics fear such development could threaten seabed ecosystems that scientists say are only now being fully understood.

Electric Power Rights of Way:

A New Frontier for Conservation

Often mowed and doused with herbicides, power transmission lines have long been a bane for environmentalists. But that’s changing, as some utilities are starting to manage these areas as potentially valuable corridors for threatened wildlife.

With the Boom in Oil and Gas,

Pipelines Proliferate in the U.S.

The rise of U.S. oil and gas production has spurred a dramatic expansion of the nation's pipeline infrastructure. As the lines reach into new communities and affect more property owners, concerns over the environmental impacts are growing.

How Norway and Russia Made

A Cod Fishery Live and Thrive

The prime cod fishing grounds of North America have been depleted or wiped out by overfishing and poor management. But in Arctic waters, Norway and Russia are working cooperatively to sustain a highly productive — and profitable — cod fishery.

A New Frontier for Fracking:

Drilling Near the Arctic Circle

Hydraulic fracturing is about to move into the Canadian Arctic, with companies exploring the region's rich shale oil deposits. But many indigenous people and conservationists have serious concerns about the impact of fracking in more fragile northern environments.

Africa’s Vultures Threatened

By An Assault on All Fronts

Vultures are being killed on an unprecedented scale across Africa, with the latest slaughter perpetrated by elephant poachers who poison the scavenging birds so they won’t give away the location of their activities.

RELATED e360 DIGEST ITEMS

13 Nov 2014: Interview: Bringing Civility and Diversity to Conservation Debate

07 Nov 2014: Organized Chinese Crime Behind Tanzania's Elephant Slaughter, Report Says

04 Nov 2014: Interview: Saving World’s Oceans Begins With Coastal Communities

31 Oct 2014: Giant Galapagos Tortoises Are Making a Strong Comeback, Researchers Say

30 Oct 2014: China Is Top Developing Nation for Clean Energy Investment, Analysis Finds

29 Oct 2014: Weather and Climate Key in Weights of Penguin Chicks, Researchers Say

24 Oct 2014: New Mapping Tool Shows U.S. Geothermal Plants and Heat Potential

23 Oct 2014: Drones Can Help Map Spread

Of Infectious Diseases, Researchers Say

22 Oct 2014: In East Coast Marshes, Goats

Take On a Notorious Invader

21 Oct 2014: Desert and Mediterranean Plants

More Resistant to Drought than Expected

Yale Environment 360 is

a publication of the

Yale School of Forestry

& Environmental Studies.

SEARCH e360

CONNECT

Twitter: YaleE360e360 on Facebook

Donate to e360

View mobile site

Bookmark

Share e360

Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe to our feed:

ABOUT

About e360Contact

Submission Guidelines

Reprints

E360 en Español

Yale Environment 360 articles are now available in Spanish and Portuguese on Universia, the online educational network.

Visit the site.

DEPARTMENTS

OpinionReports

Analysis

Interviews

Forums

e360 Digest

Podcasts

Video Reports

TOPICS

BiodiversityBusiness & Innovation

Climate

Energy

Forests

Oceans

Policy & Politics

Pollution & Health

Science & Technology

Sustainability

Urbanization

Water

REGIONS

Antarctica and the ArcticAfrica

Asia

Australia

Central & South America

Europe

Middle East

North America

e360 PHOTO GALLERY

Photographer Peter Essick documents the swift changes wrought by global warming in Antarctica, Greenland, and other far-flung places.

View the gallery.

e360 MOBILE

from Yale

Environment 360 is now available for mobile devices at e360.yale.edu/mobile.

e360 VIDEO

The Warriors of Qiugang, a Yale Environment 360 video that chronicles the story of a Chinese village’s fight against a polluting chemical plant, was nominated for a 2011 Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject). Watch the video.

Top Image: aerial view of Iceland. © Google & TerraMetrics.

e360 VIDEO

In a Yale Environment 360 video, photographer Pete McBride documents how increasing water demands have transformed the Colorado River, the lifeblood of the arid Southwest. Watch the video.

OF INTEREST

Email

Email Recommend

Recommend Tweet

Tweet Stumble Upon

Stumble Upon Share

Share Reddit

Reddit

COMMENTS

Articles like this are extremely frustrating

because there is no apparent effort by the

reporter to play more than affable stenographer.

Are we to believe industry’s statement about

operations being at the low end of the emissions

spectrum? Did the reporter merely accept the

industry PR point on faith?

To make a statement like “industry has lived with

methane leaks” makes it sound as if industry was

interested in anything other than externalizing

the costs of production. It’s been apparent from

the beginning that industry has approached

fracking with the attitude that anything likely to

negatively impact the bottom line is to be

ignored, because they can. It’s time for a sea

change. Much like all externalities associated with

oil and gas extraction, the costs of methane

capture should be internalized as a routine cost

of doing business – companies that can’t afford to

do that, or who willfully practice sloppy operating

procedures, should not be in the business.

Solutions to this problem are “taking shape”?

Sure, nearly a decade after the Energy Act of

2005. Perhaps we’d have a lot less guess work to

do now if industry had been held to adhere to

basic guidelines from the outset of the boom. To

do so of course would have thrown too many

pesky and expensive obstacles in front of the

fracking juggernaut. Better to loosen tough

regulations as industry proves it can play right,

than to start with nothing and try to convince

industry, a decade in, to clean up after itself. So

much for “clean natural gas,” another industry PR

point goes down in flames.

Instead of diverting into drones and sprinter vans

as means for monitoring fugitive methane, the

article would have been more helpful had it

focused on exactly how tougher regulations and

better efforts by industry can get us to the “less

than one percent” goal, especially given the

projected boom. We’re all – humans and non-

humans alike – living downstream from the

fracking fallout. Can we prevent a flood?

Thank you for this detailed account of how scientists, government, and industry players are making progress in addressing fugitive methane emissions. Ultimately, as Drouin writes, controlling methane emissions is an “engineering problem” — a problem that can be solved through innovation and implementation. Fracking in large part produces natural gas, a cleaner fossil fuel whose increased use has helped lower U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. We should not dismiss an entire process or energy source for a problem — methane emissions — that is not intractable.

From the article: "...getting control of methane emissions is an important issue. At heart it is an engineering problem..."

This methane wouldn't be emitted if it weren't being produced and used. It's surprising and depressing that a website apparently devoted to the environment presents such a myopic view of the issue. The way to reduce methane emissions is to stop using natural gas. That should be job 1, job 2, and job 3.

I appreciate the article. Living in Oklahoma near where a fracking boom is going on, I am well aware that a lot of methane escapes into the atmosphere — and I would suspect that the amount lost is near the higher end, though I have no measurements to show that.

Mauna Loa measurements show that the atmospheric methane concentration was about 1.69 ppm in 1987 and has now grown to about 1.81 ppm in 2011. Interestingly, the rate of growth decreased slightly after about 1998.

The best way and most cost effective way to reduce methane emissions is to not drill to extract it in the first place. Methane that comes from abandoned coal mines, existing wells, landfills, sewage treatment, digesters and feedlots, should be captured and used or flared if necessary, but drilling and using fracking to extracted should be banned. The chemicals used to frack are dangerous, the water used can not be completely recycled or made safe, and the burning of more fossil fuel will destroy and disrupt the climate. We have the technology and resources to convert to renewable energy without fossil fuel and nuclear power now. All we are lacking is the political will because the big energy companies will loose profits and have bought the politicians and brainwashed the public. Fracking is too dangerous, too expensive to be used safely and totally unnecessary for our energy needs. Read the proceedings of the Feb 26, 2014, Meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in Chicago, of Dr. Mark Jacobson's 50 State Plan for Renewable Energy for the United States Using Wind, Water and the Sun. Germany is on a similar plan. If they can do it, we can do it. They are not "wrecking their economy" nor "starving and freezing in the dark," contrary to the propaganda of the big energy and centralized electric power industries would have you believe.

I am constantly amazed that articles and the gas companies seem to think they should wait for "regulations" to force them fix the leaks. They should look to the Code or management practices that have been in effect at member companies of the American Chemistry Council. Gas companies must take the lead on locating and monitoring and eliminating all leaks to background levels. They must report their metrics to the regulators on a periodic basis. And post on a public website, invite the community in to brag about zero emissions and excellent risk management. The clean air act has had the chemical industry monitoring lots of units for leaks. Shame on the natural gas industry for being shoddy.

How about "stop fracking"? This is the ONLY answer that makes any sense.

A very interesting series of comments on natural gas. Fracking is not the only source for natural gas release into the atmosphere. Almost since the oil industry developed, natural gas has been routinely flared, probably releasing trillions of tons (or cubic meters) into the atmosphere. A 2012 NASA publication (http://www.arb.ca.gov/fuels/lcfs/lcfs_meetings/ngdc_prstn_07122012.pdf) details the complications of various methods of measuring flare volumes. Do you have, or know of, recent publications in which the flared gas volumes have been stated or referenced? It would seem that the World Bank might be a source...perhaps I missed it there.

POST A COMMENT

Comments are moderated and will be reviewed before they are posted to ensure they are on topic, relevant, and not abusive. They may be edited for length and clarity. By filling out this form, you give Yale Environment 360 permission to publish this comment.