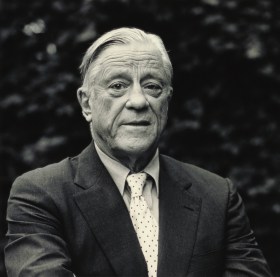

The former top editor of the New York Times remembers the man who ran the Washington Post. 'Ben had total joie de journalism,' she writes. 'It oozed from every pore'

“[Ben] Bradlee is luminescent.” The Washington Post April 19, 1981.

This is the best description of him ever. Oddly, it was published as part of the long, painful autopsy written by Bill Green, the ombudsman of The Washington Post, after the Janet Cooke scandal, certainly the Post’s, and Ben’s, lowest moment.

During that time Ben showed what he was made of. He had to return a Pulitzer Prize that Cooke had won about a made up 8-year-old heroin addict. He had to invite his boss, Donald Graham, to have breakfast at his house and tell him that he and his vaunted team of all-stars, made famous in the movie All the President’s Men, had failed the Graham family. He had to face his own crushed newsroom and, ultimately, the Post’s disappointed readers.

This would surely have brought down any other editor. So why did Ben Bradlee survive and triumph? It wasn’t simply because he was so powerful or well connected, having transformed the Post during Watergate into a national newspaper and showcase for the blazingly talented writers he hired and nurtured. Bob Woodward tried to explain Ben’s durability after the top editors at the Times lost their jobs in the Jayson Blair scandal. “Bradlee was a great editor and loved by everybody,” Woodward said. “Not just the people who knew him well, but down the ranks.”

But it was more than that. It was his great strength of character and gutsiness under fire that made him indestructible. David Halberstam, writing about Ben two years before the Cooke affair, understood this about Bradlee. In his great book, The Powers That Be, Halberstam wrote, “his own personal self-image, developed long before he went to the Post, simply did not permit him to show fear.”

Bradlee has been criticized for being too chummy with JFK and praised for the intrepid investigative reporting that brought down Richard Nixon. Watergate inspired a new generation of journalists, me included, to come to Washington and be investigative watchdogs. But lately, watching the scandal-obsessed Washington pack snarl at every pol’s ankles, it’s hard not to wonder about the proper relationship between the press and the president. Ben’s legacy as the most consequential editor of our times should provoke some thoughtful questions about this.

Ben had total joie de journalism. It oozed from every pore. No one had more fun chasing a big story and no editor made the chase more fun. He wrote his first newspaper story at age 15 as a copy boy for the Beverly Evening Times in Massachusetts. But the reporter was a born editor and during his tenure at the Post the paper won 23 Pulitzers, doubled its staff and nearly doubled its circulation. The Bradlee period was truly a golden time.

Asked by the Harvard Business Review to describe his management style in 2010, he said, “Everyone knew I had an overpowering interest in finding out the truth and getting it in the paper. They saw what made me tick, what made me smile, what turned me on. I surrounded myself with people who shared my fervor.”

One of the sadnesses of my career is that I never worked for him. I met him when I first moved to Washington in 1983 and was profiling his pal, the super lawyer Edward Bennett Williams. Ben and Ed and their third wheel, Art Buchwald, had a lunch club that had only one reason for being: to keep other people out. Katharine Graham was desperate to join, but she kept getting blackballed by one of the Three Musketeers. Finally, on her 65th birthday, she was invited in. But there was a catch: club rules required members to leave at 65. Ben roared when he told the story.

Ben loved women. Around Mrs. Graham, it was said, his walk was even jauntier and his sexy voice became raspier. He was just crazy about his wife, Sally Quinn.

He got a kick out of my climb at the Times. When I hit a rough patch there in 2003, Ben advised me to come to the Post. We met one afternoon at his favorite table in the bar at the Jefferson Hotel. Mostly, we gossiped and laughed. If he had still been in the editor’s chair, I wouldn’t have been able to resist.

One of the final times I saw him was at the last party he and Sally threw. He had started to fail and was sitting in the kitchen, surrounded by a coterie of loyal friends. Everyone still wanted to sit next to him for awhile. He was luminescent.

TIME Ideas hosts the world's leading voices, providing commentary and expertise on the most compelling events in news, society, and culture. We welcome outside contributions. To submit a piece, email ideas@time.com.