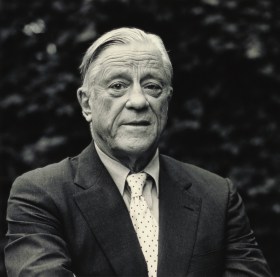

He made women feel like flowers

Oscar de la Renta was one of the greatest American designers ever. He adored women and made them beautiful. He loved flowers and he made women feel like flowers. He was a Renaissance man, the most elegant man, who befriended and was as beloved by queens and first ladies, as by seamstresses and gardeners. He was compassionate, generous and a great philanthropist. A leader in the industry, he connected with people of all ages. A skillful couturier trained in Europe and a passionate Latin man with an amazing optimism and love of life, his aesthetic sense extended to all of his surroundings, from his clothes to his homes to his gardens. He loved art and music and he loved to sing. He created joy everywhere he went.

I met Oscar when I first moved to New York. We became friends and I bought my house in Connecticut to be close to him. Every year, my husband and I spent time with him and his wife, Annette, on our boat. He loved to swim in the clear blue waters of the Mediterranean. He was forever grateful to be alive and we are forever grateful to have known him. He will stay in our hearts forever.

Diane Von Furstenberg is Founder and Co-Chairman, DVF Studio.