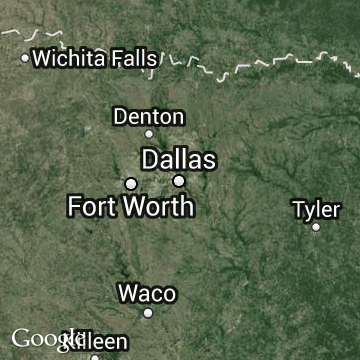

Kelton Bivins came with a slew of criminal charges when he began as a temporary worker in Dallas County’s elections department in January.

Three felonies for allegedly firing five times into an occupied car after police said he shot his cousin twice in the leg. Two charges for beating his girlfriend. Evading arrest. Bivins, 37, also was on probation for a drug charge and served time in the mid-1990s for theft.

But Dallas County officials say they weren’t aware of Bivins’ past and the criminal records of several other temps until learning about them from The Dallas Morning News.

Contractors who’ve earned millions supplying the county with temporary employees are required to do criminal background checks on their hires.

Top officials now say they aren’t certain that’s happening. County Judge Clay Jenkins said it’s unacceptable for contractors to assign employees who have criminal histories and “put our employees and the public at risk.”

Darryl Martin, the Commissioners Court administrator, said temp hiring practices will be examined — after learning of The News’ findings. And “we will make the appropriate adjustments to ensure that all employees in Dallas County meet the same set of employee standards,” he said.

County supervisors often know little about who shows up when staffing contractors send them temps. That’s even after a temp using a false name once stole $1,360 from the tax office.

The county’s limited records on temps also make it difficult for anyone to find out. Officials could not recall when, if ever, a temporary worker contract was audited.

“We have to have individuals working for us who the public can have trust in,” said human resources director Mattye Mauldin-Taylor. “And we don’t want the police coming in and putting handcuffs on people. It disrupts my work environment.”

Several vendors who have supplied temps said they conduct background checks. Two firms called it an unintentional mistake that some workers slipped through.

Because of the county’s reliance on temps, The News conducted its own background checks into dozens assigned in a variety of departments in recent years. It found:

A temp assigned to the elections department was on probation for felony theft. She still is. She also had completed probation for a misdemeanor theft charge shortly after she started her county assignment.

A temporary accounting clerk worked in the county’s Health and Human Services department while on probation for a public lewdness charge.

Another accounting clerk was working there not long after he finished probation for felony theft for falsifying documents at the Hyatt Regency in Dallas to steal more than $26,600.

A data entry clerk charged with felony assault in the beating of her son was on probation when she worked as a temp for Health and Human Services.

Another data entry clerk who worked on and off over three years for HHS had outstanding traffic warrants dating back almost a decade. She began in April as a clerk for the district attorney’s office.

And a nurse was assigned to HHS as a temp about 18 months after being convicted of misdemeanor theft. He was accused of snatching $69 from a restaurant cash register.

Such backgrounds might derail an application for a full-time county position. County officials said that having a criminal history would not automatically block a temp’s employment, but they at least want to know about it.

Dallas County HHS director Zachary Thompson, whose department has spent the most money on temps in recent years, declined to comment. He referred The News to a lawyer representing the county, and Martin, the county administrator, later issued a response on his behalf.

Other county officials said they were surprised to learn about the criminal histories.

Mauldin-Taylor said a contractor is supposed to disclose a temp’s criminal history to the department head. It is then up to the department head to decide whether to use the person.

Elections Administrator Toni Pippins-Poole said she assumed that contractors vetted their workers. She said she’s never been told about a temp’s criminal history.

“They’re supposed to give us that information,” she said.

She said she was disturbed by Bivins’ felony background and that he’s no longer working for her.

Attempts to reach him were unsuccessful.

Mauldin-Taylor said Ad-A-Staff, one of the county’s staffing contractors, told her that Bivins’ legal problems accidentally were overlooked. She said Ad-A-Staff also told her that other temps placed had no issues that would disqualify them from employment under the roughly $2.5 million contract awarded by the county earlier this year.

Ad-A-Staff president Marie Mumme said she was checking with the companies that run background checks on her temps to find out how some criminal histories could have been missed. She said she uses two companies because such checks are not always accurate.

Mauldin-Taylor said the county relies on the contractors to do the backgrounding. “That was part of the contractual obligation for the temporary staffing agencies,” she said.

Some temps, like Bivins, continued to work for the county even when the contractors changed, a common practice in North Texas. Records show Bivins worked for Chartwell Staffing Solutions in January. In June, Ad-A-Staff was handling his time card.

Mauldin-Taylor said Ad-A-Staff told her it didn’t know whether its employees were screened for arrest warrants. Such checks are routine for county employees, she said.

Mauldin-Taylor said she plans to meet with staffing contractors to ensure they know what’s required. She said they should be doing the same reviews as the county does for its job applicants. That includes looking for warrants and overdue fines and fees.

“They have to meet the same standards. I can’t afford anything less than that,” she said. “They’re on my premises. They’re doing my work.”

County auditor Virginia Porter said her office “doesn’t have a mechanism in place” to verify that temp employment agencies are conducting the critical reviews.

Little to go on

The News obtained county records on contract-supplied temps that often had little more than a name. That made it difficult and sometimes impossible to confirm the identities of many temps and determine whether they had criminal records.

For two temps, there was no public record of a driver’s license, a Texas address or any other public record.

The most detailed record typically available to county officials is a time card. It generally has the temp’s name, signature and often a Social Security number. On some, names were misspelled — including a recent time card for Bivins. Signatures were omitted on others. The clerk in the DA’s office had submitted time cards under two last names over the years.

Some computer records used by the county’s auditors and its human resources department only list the temp’s last name and do not show where they work. As a result, county officials may not know how long temps have been on the job, if they are related to a county employee or if they have a criminal background.

HHS typically pays for its temps with state and federal grant money. HHS does not need budget office approval if it’s spending grant money, officials said. Other departments have limited money for temps and must justify their use.

The health department was authorized, for example, to pay a staffing contractor $2.3 million in 2011. All but $56,500 of that was grant money.

Case in point

That contractor was All Temps 1 Personnel. It was the largest beneficiary of county contracts for temporary labor over the past decade. It also staffs the North Central Texas Regional Certification Agency, which certifies whether local companies are owned by minorities or women.

The News found that several of the employees provided by All Temps to Dallas County had criminal records.

The county has paid All Temps more than $13 million for supplying temporary workers since 2002. All Temps did not bid on the current contract for temps.

The News began looking at the role of government temp workers more than two years ago. It found that the entire staff of the taxpayer-funded NCTRCA is supplied by All Temps, which also bids on public contracts.

Gwen Wilson, an All Temps executive, said her company uses a private firm that maintains a criminal records database for background checks.

In one case, she said the company was aware of the criminal record found by The News and that the county approved the hire. Another temp got into trouble after she began working for All Temps, Wilson said. As for others, she said there was “no background found at time of hire.”

County officials had raised concerns about another All Temps employee in 2008.

That employee worked in the tax office “under a false name and encountered problems on previous work assignments, unbeknownst to both Dallas County and the Tax Office,” according to a letter from the district attorney’s office to All Temps.

The worker stole $1,360, according to the DA’s office.

The letter said All Temps failed to “provide qualified temporary agents and perform adequate criminal background checks.” As a result, the DA’s office alleged, the company breached its contract.

The letter demanded that All Temps reimburse the county and return the money it was paid for temporary personnel services that “Dallas County deems to be unsatisfactory.”

All Temps CEO Ronald L. Hay has told The News his firm’s background search “did not reveal any negative information about this employee.”

Wilson said the worker was fired and Dallas County got restitution. The crime was reported to the DA. “The entire issue was resolved to both parties’ satisfaction,” she said.

Hay said in a recent statement that his company has a record of “exemplary service.” The company’s reputation and business ethics “have always been impeccable,” he said.

Former Dallas County tax assessor-collector David Childs said he didn’t recall the theft. But he said he decided to stop using temp agency workers for other reasons before he left office at the end of 2008.

‘Good ones’ leave

Childs said his office hired several who worked for a month or two. And just as they became knowledgeable and skilled in the job, they would leave after getting offered something full time, he said.

The “good ones” left, he said. “And the ones who were unmotivated and were just kind of showing up to draw a paycheck we ended up having forever.”

John Ames, the current tax assessor-collector, said he would never be in favor of using temps provided by a contractor. Ames does hire temporary and seasonal workers, but they are county employees. They go through a county-mandated background check. And they’re issued county identification badges. Temp agency workers typically don’t go through that process.

“If somebody is going to work in the tax office, because it is such a sensitive position, I want to know their background,” Ames said. “I want them to be actual county employees, whether they are seasonal employees or part-time employees or full time.”

The sheriff and DA’s offices rely on contractors for background checks but sometimes do their own if the temps are in certain areas, said Debbie Denmon, spokeswoman for District Attorney Craig Watkins.

Denmon said the clerk assigned to the DA’s office in April had outstanding warrants and that the contractor did not tell the county that.

“The temp agency dropped the ball,” she said.

Dallas County has the right to review the performance of contractors that provide temporary labor. But the county hasn’t done so, said Porter, the county auditor.

Her office periodically looks at some of the county’s top 100 vendors. It recently sent out an “internal control questionnaire” to a temp agency in that group, but she said it’s not a “full audit.”

Employed for years

Some local government audits have recommended that temporary employees be used on a short-term basis. The News found that some temp agency employees appear to have worked in county jobs for years, mostly for the health department.

Jenkins said if temps are used to fill long-term positions, department heads should decide promptly whether to hire them as county employees. The reason, he said, is fairness to the employees. Temps typically earn less than county employees.

Unlike some other local governments, the county does not have a policy limiting how long temporary agency employees can work. The county’s contract says all job assignments will be “as needed.”

The human resources department deals directly with the temporary agencies when workers are needed. But departments are supposed to track how many hours they work and certify time sheets, Mauldin-Taylor said.

She said lengthy job assignments wouldn’t necessarily be inappropriate under the county’s current policy, but it probably should prompt questions.

“If you’ve employed them for three to four years, then why have you not hired them on a permanent basis?” Mauldin-Taylor said, adding she believes that’s “a legitimate business question that every business probably should ask.”

Targeting temp worker abuses

Audits by some local governments have uncovered abuses, sloppiness and mistakes involving temporary workers. Among them:

A city of Dallas audit in 2011 found that a city employee was supervising his son, a worker provided by a temporary employment agency that was not identified. The son was working under a different name.

The city employee retired shortly after being placed on leave, and the contract was awarded to a different firm.

Dallas formed a temporary employee task force in 2011. That came after officials discovered that high-level city employees retired and often went back to work for the city as temporary employees for a contractor.

The task force recommended a six-month waiting period before retirees could be rehired as temps, and greater oversight of those employees. The city approved the waiting period and the city manager now must approve the re-hire of retirees.

The Dallas Independent School District recently discovered that it paid a staffing firm for work even though the firm didn’t have a contract with the district at the time.

The 2013 DISD audit also found invoices from several temporary agencies lacked detail and contained errors.

Ed Timms and Kevin Krause

Getting on board

Dallas County’s hiring policy says a criminal history doesn’t automatically disqualify a job candidate and that “each situation will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.” The rules for contracted temporary employees are less clear.

Several factors are considered for county employees, such as the crime, its severity and how long ago it was committed.

Minor traffic violations are not considered criminal charges for applicants. But anyone with outstanding warrants is not considered for a county job. Anyone owing the county fines, fees or taxes is ineligible for hire.

In the past, contractors have been required to perform a criminal background check on temporary employees to identify any “felonies or criminal convictions” in Texas or in the previous state where the employee lived.

A new contract approved this year requires contractors to check a national sex offender database, a national criminal records database and criminal records in the counties where applicants have lived for the past seven years.

Timeline: Bivins’ legal troubles

Kelton Bivins had unresolved legal issues when he came to work for Dallas County’s elections department as a temporary employee. Contractors are supposed to conduct criminal checks but his department head said she never knew about Bivins’ past. The Dallas Morning News identified him and several other county temps with criminal histories. Here’s a look at Bivins’ background and police and court reports:

April 1994 – Receives a deferred sentence for a misdemeanor “evading detention” charge.

August 1994 – Deferred sentence is revoked. Sentenced to 90 days in jail.

September 1994 – Gets deferred sentence on a felony theft charge.

May 1995 – Probation on the theft charge is revoked and Bivins receives a 10-year sentence.

December 2006 – Accused of hitting and kicking his girlfriend. Charged with misdemeanor assault-family violence. Case is still pending

April 2008 – Charged with a felony drug possession and a misdemeanor for evading arrest. Evading arrest case is still pending.

Dec. 12, 2008 – Receives a deferred 9-year sentence for the felony drug charge.

Dec. 14, 2008 – Accused of attacking the same woman, by then his former girlfriend. Charged with a second misdemeanor assault-family violence. The case is still pending.

May 6, 2010 – Bivins is indicted on three counts of felony “deadly conduct” in connection with a fight with his cousin. Bivins shot him twice in the left leg, according to police reports. When the cousin ran toward a car, police say, Bivins kept firing, striking the vehicle “at least five times.”

May 13, 2010 – Prosecutors seek to revoke Bivins’ deferred adjudication in the 2008 felony drug case because of the shooting.

April 2013 – The Texas attorney general’s office sues Bivins in Dallas County family court for unpaid child support.

July 2013 – Bivins is cited for a traffic offense and never paid the Dallas County fine, records show. Such debts automatically disqualify people from working for the county

Jan. 6, 2014 – County records show that Bivins was assigned as a temp to the elections department. County officials said last week Bivins no longer works there.

SOURCE: Dallas Morning News research