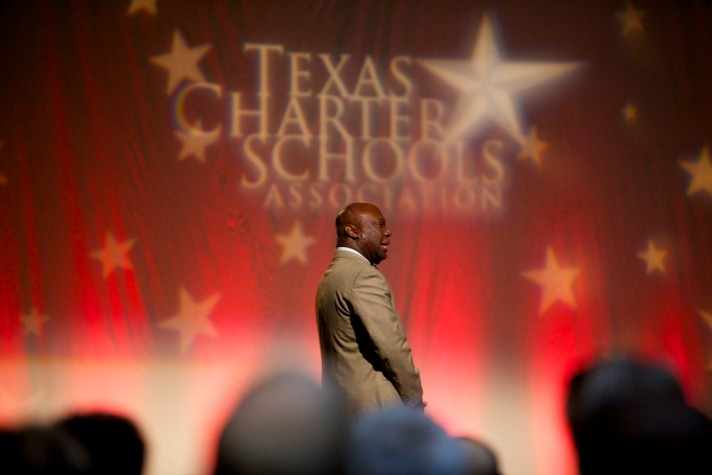

Patrick Michels

Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams speaks at a Texas Charter Schools Association conference.

For folks hoping to open a charter school in Texas, this time of year is a little like spring training: full of possibility for the bright future ahead, lots of idealism mixed with meticulous planning.

And every year in mid-July, during intense, hours-long interviews in Austin, state regulators take their turns dumping buckets of cold water on the would-be school operators. Having picked over the schools’ epic applications—this year’s longest is 648 pages—Texas Education Agency staff and State Board of Education members probe the applicants for weakness, grill them on financing, on their grasp of federal law, on their typos, offering at least a taste of the greatest challenge of all: keeping the school running once it opens.

Ten applicants were invited to in-person interviews this week, which wrapped up Wednesday. The meetings were long and intense, with tears, applause, and more than a few awkward pauses to explain, for example, what looked like plagiarism in one application.

Though lawmakers want to grow Texas’ charter school offerings, it’s one of the smallest applicant pools ever, with none of the out-of-state networks state leaders are so enthusiastic about. California-based Rocketship Education—the most high-profile applicant this year—pulled its application this month.

To judge by last year’s class, only a few of the remaining 10 will get the green light from Education Commissioner Michael Williams (and the SBOE has the chance to veto any of his picks after that). With no big charter-school brand names in the mix, the remaining 10 proposals offer a fascinating look at locally raised ideas for giving students programs they need. Some are small, some are really big; four (by my estimation) have vaguely religious roots; some come from well-established local nonprofits; one is from a team of Texas’ best-connected education researchers.

So if you’re scoring at home, here are the latest applications, along with my notes. These applications are long and detailed—often padded with generalities and jargon that’s hard to pin down (hello, “brain-based learning“)—and the state has the benefit of reviewers with actual qualifications. Texas even contracted with a national charter school group to provide training on the interview process.

Below, I’ve included a few things I found most interesting about each school. If anything else catches your eye about an application, I’d love to hear about it in the comments. Click on the school’s name and you can read the full application—the state has them online as PDFs, but the files are big and unsearchable. Our links go to searchable versions on DocumentCloud that you can read without downloading.

Athlos Academy

Where: 15 campuses in Dallas and Tarrant counties, likely beginning in East Dallas

Grades: K-8, expanding to K-12

Who’s behind it: Edward Conger, Martha Rocha, Paul Reyes, Erin Ragsdale. Conger is superintendent at another charter school, International Leadership of Texas. Rocha is a director at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, and Ragsdale is an executive at Dallas political communications firm Allyn Media.

Their proposal:

A school built on Athlos’ “three pillars of excellence: Prepared Mind, Healthy Body, and Strong Character.” The application focuses on the achievement gap in state test scores, but also on students’ health and well-being and sports, with a P.E. program developed by California-based Velocity Sports. The school would have after-school sports, but not contact football. “We view athletics as a tool that when utilized to its full extent, has the ability to improve the mind, body and character.” Students can get instruction in English, Spanish and Chinese, and Dual Language Immersion for English. A charter school with a similar approach, Athlos Leadership Academy, is opening in San Antonio this fall (under a pre-existing charter for the Jubilee Academic Center). Athlos is Greek for “feat” or “achievement.”

Beta Academy

Where: 3 campuses in Houston/Harris County

Grades: K-6, expanding to K-12

Who’s behind it:

Latisha Andrews, Martha Smith, Philip Smith, Reba Blakey, Teresa Sones. Andrews is director of Responsive Education Solutions’ Vista Academy charter school, and a former principal at Life Christian Academy, both in Houston. Sones chairs the sponsoring Beta Foundation. Philip Smith is a program manager at Raytheon.

Their proposal:

This is Andrews’ third time pitching the state on a charter—last year the Texas Tribune featured Andrews and Beta in a piece about charter schools in churches:

Andrews started Beta Academy after her own church, which is across the street from Christian Temple and where her husband is a pastor, closed its private school because of declining enrollment.

Beta promises “a world-class school” with “a culture of ‘joyful rigor.'” Supplemental programs would include aviation, Scrabble, and fundraising for the Invisible Children campaign.

Brentwood Stair Preparatory School

Where: 1 campus in Fort Worth

Grades: Pre-K to 8

Who’s behind it:

Julia Michelle Nusrallah, Nabil Bawa, Walid Joulani, Alex Farr, Nizam Peerwani, much of the leadership from the sponsoring nonprofit, the private Al-Hedayah Academy. Peerwani is Tarrant County’s chief medical examiner and sits on the Texas Forensic Science Commission.

Their proposal:

The school would also locate at Al-Hedayah’s campus near I-30 in west Fort Worth. “The Al-Hedayah Academy wants to ensure that families who have previously expressed a desire to attend but may not have been able to afford the tuition are given a chance to enroll.” Brentwood Stair’s team promises a “non-parochial school” with a “richly diverse faculty and staff.” Students can learn Spanish or Arabic, and teachers will encourage students’ self-discovery and differentiated learning.

Excel Center

Where: 1 campus in Austin

Grades: 9-12

Who’s behind it:

Traci Berry, Dodie Brown, Roberta Schwartz and other leadership generally come from Goodwill Industries of Central Texas.

Their proposal:

Excel Center applied last year, too, promising a dropout recovery school for “older youth and young adults up to age 25,” with a twin focus on diplomas and career skills. A similar school run by Goodwill has opened in Indianapolis, which was featured on PBS NewsHour in January. The Austin location would be at the Goodwill location at Anderson Lane and I-35.

Foundations Charter School

Where: 50 (!) campuses of 50-100 students each surrounding Dallas and Houston

Grades: Pre-K to 2, expanding to pre-K to 5

Who’s behind it:

Steve Edwards, David Greak, Michael Owens, Don Hooper, Susan Landry, Lonnie Hutson. Edwards’ Ignitus Worldwide is the charter sponsor. Owens and Greak are associated with Texas Successful Charter Schools, a charter school support company that would also partner with this school. Landry leads the Children’s Learning Institute at the UT Health Science Center, which has (somewhat controversially) become a powerhouse in Texas’ pre-K world. Hutson runs a series of pre-K centers around Houston. Schools would locate at pre-existing child care and early ed facilities. Former state Rep. Rob Eissler (R-The Woodlands) is also on the school board.

Their proposal:

An innovative, research-based focus on early education to keep students from falling behind before the “learning gap” develops, promising what Landry calls “a seamless link” into later grades. Instruction—offered year-round or on a traditional schedule—would be “presented in the context of a relevant or coherent ‘whole.'” The school would partner with the UT Health Science Center’s Children’s Learning Institute—which developed a number of programs the school would use—and specifically mentions an agreement with the online Western Governor’s University to provide a pipeline of new teachers. The TEKS Resource System (neé CSCOPE) would help map the curriculum.

High Point Academy

Where: 3 campuses in Fort Worth, first in west Fort Worth

Grades: K-8, expanding to K-12

Who’s behind it:

Katie Stellar, Lori Manning and Dana Yates. Stellar is, according to her LinkedIn profile, executive director of Faith In Action Fort Worth—the nonprofit sponsoring High Point Academy’s charter—a former art teacher, owner of a custom T-shirt firm and an ordained Methodist minister. Manning is a former principal at Fort Worth’s Pinnacle Academy of the Arts, one of seven campuses under the umbrella of Honors Academy—which Texas Education Commissioner has moved to revoke after three years of subpar test scores. The group is opening its first charter school this fall in Manning’s hometown of Spartanburg, South Carolina. The group applied in Texas last year too, but Stellar pulled its application after learning parts of it had been plagiarized.

Their proposal:

High Point promises a focus on STEAM instruction—that’s science, technology, engineering and math, plus art—and will use the Texas Resource Management System (neé CSCOPE) and E.D. Hirsch‘s “Core Knowledge” program. They’ll offer before- and after-school programs including Zumba and Krav Maga, and tablets and laptops for textbooks.

Ki Charter Academy

Where: 1 campus in San Marcos

Grades: 1-12

Who’s behind it:

Lura Davidson, Ruben Garza, Trinidad San Miguel. Davidson is an adjunct professor at Concordia University. Garza and San Miguel are instructors at Texas State University.

Their proposal:

A school for students in state residential facilities (RFs), with plans to partner with the largest RF in the state, the San Marcos Treatment Center. School would top out at 220 students, and focus on an “underrepresented and high-needs population” with a curriculum including Scholastic’s boxed Read 180 and Math 180 programs, and the “Pitsco STEM/CTE Modular laboratory,” a short-term program with a 2-to-1 student-teacher ratio.

Royal Ambassador Academy

Where: 1 campus in Beaumont

Grades: Pre-K to 4, expanding to pre-K to 8

Who’s behind it:

Johnny Brown, Rev. John Adolph, Felicia Young. Adolph is pastor of the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church. Brown is CEO of the J&C Brown Institute for Learning, and a former superintendent at ISDs including Wilmer-Hutchins and Port Arthur. Young and other leaders come from the sponsoring nonprofit, the Jehovah Jireh Village Community Development Center.

Their proposal:

A Montessori program with a STEAM—science, technology, engineering and math, plus art—focus, plus character (social, emotional and moral) education and strong parent involvement. The school would be located at the Antioch Missionary Baptist Church.

SA Youth Youthbuild Academy

Where: 1 campus in Central San Antonio

Grades: 9-12

Who’s behind it:

Cynthia Le Monds, and other SA Youth leadership. “SA Youth is one of the largest and most respected youth serving organizations in San Antonio,” according to the application, a 30-year-old nonprofit focused on “high-risk urban youth.”

Their proposal:

Built on the Youthbuild model developed decades ago in Harlem, a year-round high school for students, most ages 16 to 24, who’ve dropped out of traditional schools—basically the students SA Youth already serves. They’ll prevent kids from dropping out again by building tight-knit, family-style cohorts for both classroom and career education. Instruction will be self-paced, including online coursework, a web-based curriculum like Plato Courseworks, and direct instruction from teachers who’ll be “on call” in the evenings.

Trinity Environmental Academy

Where: 1 campus in South Dallas, “near Great Trinity Forest”

Grades: K-1 and 6, expanding to Pre-K to 12

Who’s behind it:

Jennifer Hoag, Lisa Tatum, Dhriti Pandya, Michael Hooten. Hooten comes from the well-established North Texas charter chain Uplift Education. Sustainable Education Solutions is the nonprofit behind the application.

Their proposal:

A school in a high-need South Dallas location taking advantage of its proximity to the Great Trinity Forest, “the largest urban hardwood bottomland forest in North America.” Students would conduct “local environmental field investigation,” with classroom programs built on environmental education, health, sustainability, STEM, civic skills, and “green career pathways.” The Trinity River Audubon Center and Paul Quinn College’s football-field/garden would offer more connections between the school, the community and the environment.