Six days a week, bumping through the scrub, oil trucks pull up to the rail stations at Muleshoe or Kermit, Dimmit or Roy, Whiteface, Seagraves or Wellman, any of the flyspeck boomtowns of the Permian Basin.

By the tracks, roustabouts and railroaders meet for a transfer as old as their industries. Pumping crude into tank cars, they step back as the locomotives lurch off toward the transfer stations of BNSF and Union Pacific, the two big lines that crisscross the state on their way to Houston, where 800 miles of track wind through the city toward the petroleum barges and refineries of the Gulf Coast.

“First mile in the delivery process,” says Bruce Carswell, operations manager of the West Texas & Lubbock Railway. His telephone manner, ever polite, turns gently defensive when he adds: “Railroads have been handling this sort of commodity and other hazardous commodities for many, many years. The vast, vast, vast majority of these shipments never have a problem.”

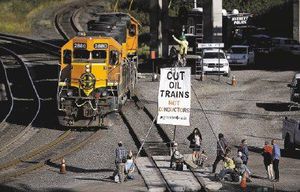

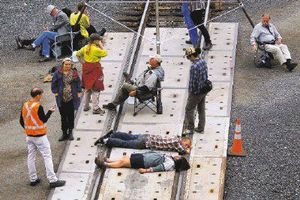

Across the country, intense scrutiny has descended on rail transit of crude, a partnership that built the national energy system in the age of John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil. As traffic has surged, a series of accidents, including a spectacular derailment that killed dozens of people last summer in Canada, has led to outcry from fire marshals and assurances from rail industry officials. Federal officials have issued a safety warning and emergency orders. Tensions have escalated rapidly, with protestors blocking the tracks outside a refinery recently in the Pacific Northwest.

But in Texas, home of the country’s most prolific production, biggest proved oil reserves and most expansive refining capacity, crude oil rides the rails with little oversight. To fulfill the minimum requirements of a federal emergency order, state public safety officials have agreed to receive some information about potentially volatile crude arriving from a subterranean formation in North Dakota. They do not, however, assess the cargo originating in Texas, passing through from other places or moving toward the great global hub of Houston. They do not test its flammability. They do not, in any significant detail, track its quantities, movements or destinations.

Now, as federal officials begin testing some wells in South Texas for the same explosive properties found in northern samples, some experts say the state may be taking a serious safety risk by turning a blind eye to the crude churning through its rapidly expanding rail networks.

“Nobody really keeps track of it,” said Sandy Fielden, an industry analyst in Austin for the consulting firm RBN Energy. “As far as the safety of it, the jury is still out.”

Extraordinary glut

For generations of drillers in Texas, where a vast pipeline system has grown with the fits and starts of the oil industry’s notorious business cycle, railroads provided little more than a relatively expensive last resort. But in the new boom associated with the hydraulic fracturing technique known as fracking, producers have increasingly enlisted trains to handle the extraordinary glut.

Nationally, according to the Association of American Railroads, carloads of crude oil grew from 9,500 in 2008 to more than 400,000 this past year. In the first quarter of this year, the most recent figures available from the association, crude shipments grew to 110,000 compared with 97,000 in the first quarter of 2013.

By the most recent data available from the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industries (but not the railroads), combined rail and barge shipments of oil and oil-like substances rose from about 360,000 barrels in 2011 to about 401,000 barrels in 2012. The commission could only estimate how much of that traffic represented rail shipments, putting the figure at 90 percent.

The danger announced itself in July 2013, when a runaway train carrying 72 tank cars smashed into the small tourist town of Le Mégantic, Quebec, killing 47 people. The oil on board — 30,000 gallons per car — had come from the Bakken formation in the Williston Basin of North Dakota. A month later, U.S. officials from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration started making unannounced inspections of producers in the region.

In May, based on the early results of the operation, the U.S. Department of Transportation issued a safety warning. Citing the volume of crude oil coming out of the Bakken, officials urged the railroads to take extra precautions, using tank cars with the “highest level of integrity reasonably available within their fleet.”

Longstanding federal regulations require trains carrying hazardous materials to be marked with a diamond-shaped placard for the benefit of emergency responders. Along with the new safety warning, the department issued an emergency order requiring railroads to take the additional step of notifying state safety officials across the country of any incoming train carrying more than a million barrels of crude from the Bakken.

Oil and gas industry officials responded quickly, contesting any need for the notifications. In a report issued a week after the federal safety warning, the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers, a trade group representing manufacturers of products including gasoline and home heating oil, argued that “Bakken crude is comparable to other light crudes and does not pose risks that are significantly different than other crudes or flammable liquids authorized for rail transport.”

Notice of shipments

In Texas, the duty of receiving the notifications fell to a division of the state Department of Public Safety. “We’re just the repository they have to report to if they meet that threshold, which is extremely high,” said Tom Vinger, a spokesman for the department. One of the state’s two main rail operators, Union Pacific, “gave us information that said, ’We don’t have anything that meets the federal threshold, have a nice day.’ ”

The other big rail line, BNSF, did provide notice of shipments from the Bakken, according to Vinger. State officials in turn notified the appropriate counties, he said, though he declined to specify the number of shipments, the counties involved or whether the notice inspired any particular safety precautions. Presented with a request for that information under the state open records law, the department’s lawyers sought an opinion from the attorney general. They argued that the records might be exempted from public disclosure because the railroad had marked them “confidential.” The attorney general has not yet issued a decision.

In Houston, Bob Royall, assistant chief for emergency operations at the Harris County Fire Marshal’s Office, said he did receive an email notification from state transportation authorities. It was informative, in a limited way. It disclosed that an average of two trains a month enter the county carrying Bakken crude in excess of the million-gallon federal threshold. That amount, he noted, would fill about 35 tank cars. “There is no vehicle for us to determine if there is a train with less than the threshold coming through,” Royall said. Asked to describe any safety concerns regarding a train too small to meet the threshold, he added, “A 25- or 30-car derailment is going to be a catastrophic event that will tax the resources of any department.”

Spokesmen for BNSF and Union Pacific declined repeated interview requests, referring instead to the industry’s written statements on the topic.

But some officials have begun to suspect a problem too pervasive to pin solely on production volume in North Dakota. Derailments, spills and fires involving crude from several different regions have caused damage in Minnesota, Mississippi, Alabama and Lynchburg, Virginia, where thousands of gallons of crude tainted the James River.

In June, Sens. Ronald Wyden and Jeffrey Merkley, Democrats of Oregon, where rail cars deliver crude to terminals in Portland, publicly questioned the focus on oil production volumes in North Dakota. Is it possible, they asked in a letter to the National Transportation Safety Board, that “crude oil produced outside of the Bakken and transported on railroads poses potential hazards in the case of an accident?”

Spills from rail cars

There was a time when years would go by between oil spills from rail cars in Texas. This is a true fact: In the 1990s, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl more often than federal officials counted a crude spill from a train in their state. Since the escalation of the fracking phenomenon in 2010, though, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has counted 68 such spills, compared with a total of nine in the entire previous 40 years.

There have been eight spills this year but with no injuries.

But their numbers have sharply increased even as other aspects of rail safety have improved. Over the past decade, according to statistics from the Federal Railroad Administration, accidents and derailments showed a steady decline in Texas, reflecting the nationwide trend.

As the oil boom accelerates, with Texas production reaching 3 million barrels a day this year for the first time since the 1970s, rail companies are expanding to carry more crude through the state. US Development Group has assembled a network of specialized facilities. Rangeland Energy, based in Sugar Land, is building a rail terminal near Loving, New Mexico, set to open in October with high speed trains eventually shipping 100,000 barrels a day. Facilities including Southton Rail Yard and Alamo Junction Rail Park are expanding their rail capacity to serve the wells of Eagle Ford south of San Antonio. And in Port Arthur, Global Partners recently announced plans to build a 200-acre rail terminal capable of receiving two oil trains a day and storing 340,000 barrels of crude.

Rail industry executives say they can maintain safety as they expand to carry more oil.

In recent months, federal officials have been expanding their focus from the volume of crude oil to the composition. Oil from the Bakken, the department said in a report, has “a higher gas content, higher vapor pressure, lower flash point and boiling point and thus a higher degree of volatility than most other crudes in the U.S., which correlates to increased ignitability and flammability.”

Now, according to Gordon Delcambre, a spokesman for the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration in Washington, inspectors are making unannounced visits to oil producers in Texas. So far, they have gathered samples from “half a dozen” hoses pumping crude from the Eagle Ford Shale formation into rail tank cars. He described the testing as “due diligence as far as safety is concerned to make sure we understand the composition of the material coming out of the ground.”

Hazardous material

To a certain extent, it is not difficult to determine the properties of a batch of oil. Using a fairly simple field test, producers routinely measure the density on a scale known as the API Gravity. Higher numbers mean lighter oils, less diluted and more valuable at the refinery cash register. In Texas, producers report the results to the state Railroad Commission.

But while crude oil is, by definition, a hazardous material, determining properties like explosiveness requires more extensive composition testing in the laboratory. Producers have little motivation to undertake that analysis, though some do take costly steps to stabilize their crude by removing components like methane and butane.

“How volatile is volatile?” said Paul Bommer, a petroleum engineering expert at the University of Texas at Austin. “That’s a tough question to answer. You’d have to take your bucket of oil to the lab and do some sort of flammability test.”

In an emergency, some experts say, the origin of the crude may turn out to matter little.

“At the end of the day, you have flammable liquids that burn in rail cars, about 22,000 gallons of it per rail car, about eight times what’s in a tractor-trailer,” said Sam Goldwater, a fire and rail safety consultant based in San Antonio. “If your expectation is that my fire department should be able to put out a tractor-trailer fire at the Shell station, how do you feel about something eight times bigger?“

Across the country, fire officials have requested emergency funds to prepare for a derailment. The U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee has approved a bill that would devote $2 million to specialized training, and the rail industry has paid to fly firefighters in for three-day seminars at a facility in Colorado. On Aug. 22, the Federal Railroad Administration announced $350,000 in grants to finance safety efforts for short line railroads.

The U.S. Department of Transportation has proposed new regulations on rail worker training, oil composition testing, train speed and tank car construction. Responding to the proposal, Edward R. Hamberger, president of the American Association of Railroads, promised cooperation.

Out in the far-flung oil towns of Texas, as they watch their cargo pull away from the train station, drillers can expect their shipments will usually reach their destination safely. Railroads consistently spill less oil than other modes of land transport, and the amounts of spillage declined between the 1990s and more recent years, according to a report issued in May by the Congressional Research Service.

Still, some view the tank cars rolling through the state with wary eyes.

“Most of the rail lines go right through the center of Houston on their way to the refineries,” said Tom Smith, director of the Texas office of the government and industry watchdog group Public Citizen. “In all likelihood, this is a disaster waiting to happen.”